Chapter 1: The Early Years, 1872-1910s

Scott's reason for endowing the university was expressed in this pamphlet, first published in 1868, entitled "Toledo: Future Great City of the World." To fulfill its destiny, Toledo needed an institution to train its young people. Shown here is the title page of a reprint of the pamphlet's second edition. (The Blade Printing and Paper Company, 1937.)

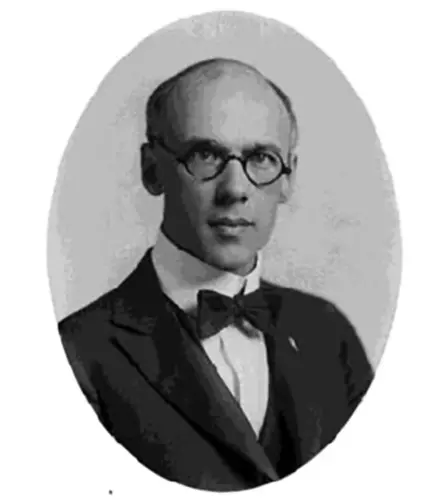

Jesup Wakeman Scott, newspaper publisher and real estate broker, who donated 160 acres in 1872 as an endowment for the Toledo University of Arts and Trades.

In a small pamphlet published in 1868 entitled “Toledo: Future Great City of the World,” Jesup Wakeman Scott articulated a dream that led him to endow what would become the University of Toledo. Scott, who served as editor of The Toledo Blade from 1844-1847, often used his writings to promote the city. In this publication, he expressed his belief that the center of world commerce was moving ever westward, and by 1900 would be located in Toledo. The city would become bigger than Paris, London, or New York. To help realize this dream, in 1872 Scott donated 160 acres of land on Nebraska Avenue near a proposed railroad terminal as an endowment for a university to train the city’s young people to assume roles in the Future Great City.

Articles of incorporation were drawn up on October 12, 1872 for the Toledo University of Arts and Trades. The institution was to “furnish artists and artisans with the best facilities for a high culture in their professions....” Income from the lease of the Scott land, then valued at $80,000 but certain to increase rapidly when the railroad terminal opened, was to support the institution. The university was to offer its classes “free of cost to all pupils who have not the means to pay for the same, and all others are to pay such tuition and other fees as the trustees may require.”

Unfortunately for the struggling university, the railroad terminal never materialized. Jesup Scott died in 1874, a year before the university opened in the old Independent Church Building at 10th and Adams downtown. The building was named for trustee William Raymond, who gave the money needed to purchase it. The university’s curriculum centered on design courses, with painting and architectural drawing as the only subjects. The school was forced to close in 1878, however, because it was never able to gain appropriate finances.

Jesup Scott’s three sons—Frank, William, and Maurice—were disappointed by the failure of the school. They felt that the university might succeed if reorganized as a manual training school. But because they had no money, the sons turned over the university’s assets—including the 160 acres of land—to the city of Toledo on January 8, 1884. Three months later the city accepted the gift and agreed to use the assets to create a university, as was required by the Scott trust.

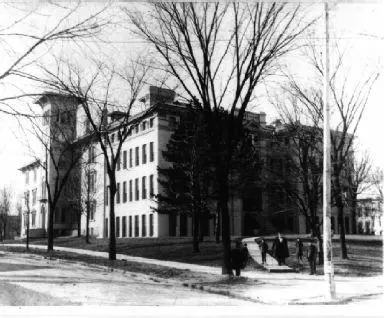

After being reestablished as the Toledo Manual Training School in 1884, the school moved into an annex of Central High School a year later.

The city ordinance accepting the assets stated that the school was to be called Toledo University, and its first department was to be the Manual Training School. A Board of Directors was appointed, and the Toledo Board of Education provided the top floor of the Central High School to house the Manual Training School. The school offered a three-year program for students at least 13 years old, who divided their time evenly between academic and manual instruction.

The Manual Training School was a huge success. Soon the school was out of room, and the Board of Directors asked the Board of Education to provide land for a new building. The ensuing disagreements between these two governing bodies were the first in a long line of fights which would not be resolved until 1911. But the new building was constructed as an annex to Central High.

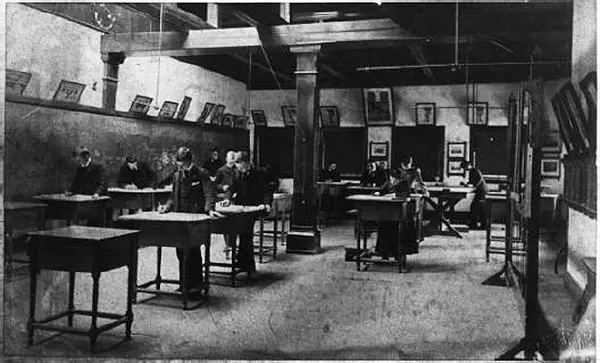

The Toledo Manual Training School offered a three-year program for students 13 years of age and older divided between academic and manual training.

Women were admitted to the school beginning in 1886.

A coeducational class in mechanical drawing at the Toledo Manual Training School, ca. 1890.

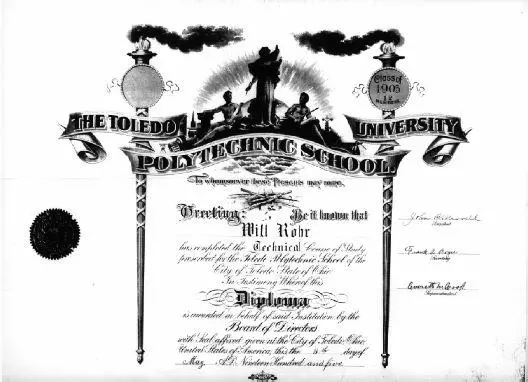

In 1900, the school changed its name to the Toledo University Polytechnic School, although most people still referred to it as the Manual Training School. Student Wi ll Rohr sued theBoard of Directors to gain admission when the directors decided to exclude students in the 8th and 9th grades due to a shortage of classroom space. Rohr was admitted, and he graduated in 1905.

Toledo University passed up a great opportunity in 1900. An anonymous donor offered to provide a substantial gift of money to turn the Manual Training School into a technical university. However, the Board of Directors turned down the offer because they felt it had too many strings attached. They learned after rejecting the gift that their would-be benefactor was steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie gave his money a few years later for the establishment of the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh.

The Manual Training School changed its name to the Toledo University Polytechnic School in 1900. However, most people continued to call it the Manual Training School, and it continued a curriculum of traditional and vocational instruction to students in the 8th grade and higher. Another quarrel broke out between the Board of Directors and the Board of Education over space for the school. When it could not be resolved, the Board of Directors decided to exclude students in grades 8 and 9 from attending. With this move, the battles between the two bodies intensified.

Albert E. Macomber, one of eight original trustees of the Toledo University of Arts and Trades, who became a vocal critic of the institution in the 1900s . (North and Oswald Photographers, Toledo , Ohio.)

Albert E. Macomber, one of the original trustees of the institution in 1872 and an ardent supporter, suddenly turned on the school and began a lengthy battle against it. He sought to have the Polytechnic School abolished and reestablished as the manual training department of Central High. Maurice Scott supported Macomber because he felt the Polytechnic School was not the intention of his father’s original endowment.

The university’s Board of Directors needed a new facility to relieve overcrowding, and proposed selling the Scott farm property to pay for it. Macomber and the Scott sons sued, stating that the city and the Board of Education had no right to sell the land. The university’s Board of Directors turned to the state legislature, which in 1904 enacted legislation stating the right to regulate municipal universities was a power of city council, not the Board of Education. A circuit court ruling upheld the legality of the Board of Directors.

The battle between the two governing boards continued, and escalated. In 1905, the Board of Education refused to levy taxes to support the school, and the Manual Training School could not open for one month due to lack of funds. The next year the Board of Education sought to strengthen its hand by seizing the building that housed the school. Several members barricaded themselves inside, refusing to leave. The Board of Directors asked the city to file a lawsuit to finally settle the question of who controlled the university.

Jerome H . Raymond, first president of Toledo University, 1909-1910.

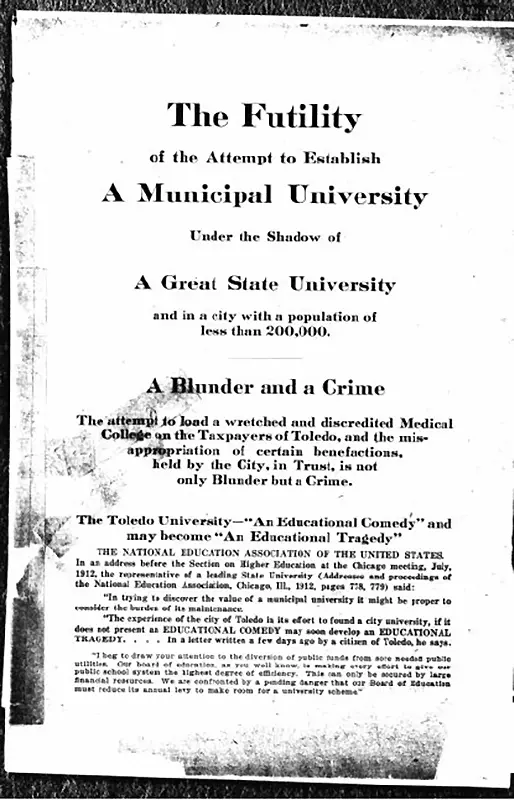

Funding for the school continued to be tenuous. In 1908, when the city tried again to levy taxes to support the institution, Macomber vigorously attacked the effort. He published a scathing circular criticizing the university. City government was unwilling to turn over any money to operate the institution until Board member Dr. John S. Pyle pointed out the city had just spent $2400 to purchase an elephant for the zoo. Surely, Dr. Pyle argued, the university was as important as an elephant. The tactic worked, and on June 15, 1909, the city granted $2400 to fund the institution. This did not end the financial problems of the university, however, and operating expenses often had to be made up out of the pockets of the directors.

Students gathered outside the entrance to the Toledo Medical College, Cherry and Page streets. The college affiliated with Toledo University in 1904.

Dr. Jerome Raymond was appointed the first president of the university in 1909. Despite the financial headaches and the on-going questions concerning the legality of the university’s existence, Dr. Raymond was able to make some progress for the university. He expanded the university’s offerings by affiliating with the Toledo Conservatory of Music and the YMCA College of Law and creating the College of Arts and Sciences. Along with its affiliation with the Toledo Medical College, which had occurred in 1904, these changes were important in moving the institution from being a manual training school to becoming an institution of higher education.

However, Dr. Raymond found the stress of the situation too much, and resigned in 1910. No candidates came forward to replace him because of the political difficulties and an annual city appropriation of only $3600. The university appointed Dr. Charles Cockayne, then on the faculty, as acting president.

Charles A. Cockayne, acting president from 1910-1914.

Undated class photograph taken in the operating amphitheater of the Toledo Medical College. The medical college was forced to close in 1914 when the American Medical Association issued new regulations governing medical education.

At this time, classes for the university were being held in both the Manual Training School facility and at the Toledo Medical College building at Cherry and Page. The Toledo Medical College building was nearly destroyed in a fire on January 9, 1911. This was a devastating blow for the directors. The university lost its laboratories, its library, and many classrooms. The directors were ready to give up and close the university. Fortunately, an arrangement was made to use the third floor of the Meredith Building at Michigan and Jefferson. The university continued to hang on.

One of the many pamphlets written by Albert Macomber criticizing the university. This one, published in 1913, said the Board of Directors extorted money from Toledo taxpayers for an unnecessary university that was little more than a diploma mill.

On January 24, 1911, in the case of Toledo v. Seiders et al., the university finally got the legal decision it had eagerly sought settling the questions of ownership and control. A circuit court decision (upheld by the Ohio Supreme Court) clearly established the legal existence of the university and the Board of Directors as its governing body. The city raised its budget to $5000, and for the first time it appeared the institution might survive.

The Board of Directors realized after the court’s decision that it no longer needed the Manual Training School. The curriculum did not fit with an institution that provided baccalaureate education. In 1914, the directors worked out an agreement to give the building to the Board of Education in exchange for an empty elementary school at the corner of 11th and Illinois. However, this building was not without its problems. It needed extensive renovation; it was in a bad neighborhood; and it was a mile from the Cherry and Page street building which, after having been repaired following the fire, continued as the location for many classes.

Allen R. Cullimore, acting president for five months in 1914.

With the new building came a new president. Dr. Cockayne was removed, although at first he refused to leave and his replacement, Dr. Allen Cullimore, had to change the locks on the president’s office door to keep him out. Dr. Cullimore served as acting president for five months until a permanent president, Dr. A. Monroe Stowe, took office on July 6, 1914.

Dr. Stowe faced many of the same challenges of his predecessors, and some new ones. In 1914, the Toledo Medical College closed, the victim of new regulations governing medical education issued by the American Medical Association. But despite this setback, Dr. Stowe seemed to have the vision to take the university on its first organized path of development. He established educational standards, admission requirements, and a formal curriculum. He founded the College of Commerce and Industry in 1914, and the College of Education in 1916. Enrollment grew from 200 students to 1400, and the budget increased to $200,000. Dr. Stowe took the first steps toward becoming accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, and in 1920 accreditation was granted.

The Board of Directors moved out of the Manual Training School building in 1914 to a renovated elementary school at 11 th and Illinois. This undated photograph shows many of the students gathered on the steps of the building.

A. Monroe Stowe, president of UT from 1914-1925.

Dr. Stowe’s tenure was not without controversy, however. In 1915, at the urging of Dr. Pyle, Dr. Stowe hired Scott Nearing as professor of economics and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Nearing was an economics professor who had been dismissed from the University of Pennsylvania for his radical views. With his national reputation, Nearing was sought after as a speaker, and came to be seen as the spokesperson for the working classes of Toledo. With the United States on the verge of entering World War I and the fear of Socialism on the rise, however, Nearing was attacked by many conservative groups in the city. They feared he was using his position in the classroom to teach Socialism to students. The groups and their influential leaders succeeded in getting Nearing dismissed from his position in 1917. His house was raided, many of his papers were confiscated, and the American Association of University Professors refused Nearing’s appeal for assistance.

Scott Nearing, a professor of economics and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, was dismissed from his position in 1917 because some community leaders believed he was teaching Socialist ideas in the classroom.

Women also participated in the war effort. These women enrolled in an automobile mechanics class at the 11 th and Illinois Street building in 1917.

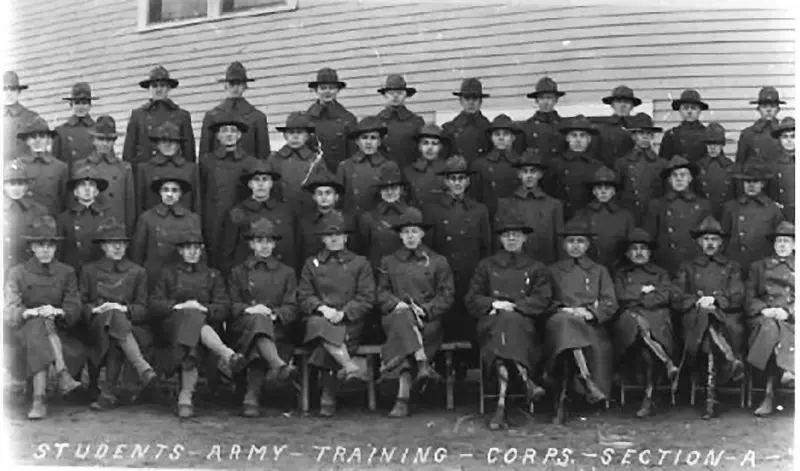

When the United States entered the war in 1917, enrollment dropped as students left to serve their country. The Committee on Education and Special Training of the U.S. War Department proposed a program to the university to train automobile mechanics for the war effort. A machine shop and dormitory were built on the Scott property on Nebraska Avenue for this purpose, as was housing for the Toledo University Section of the Students Army Training Corps. This program, the forerunner of ROTC, provided army training for many soldiers. Many of these students returned to the university after the war and enrolled as full-time students.

At the end of nearly 50 years of existence, Toledo University had emerged as a growing municipal university. While its critics, including Albert Macomber, continued to attack it, the institution had established the legality of its existence, had divorced itself from a manual training curriculum, and was accredited by a national agency. It continued, however, to be housed in several inadequate buildings, and in the next decade would be forced to find a permanent home.

Students Army Training Corps in front of the Gymnasium on the Scott land, 1918. In 1918, the U .S. War Department created the Students Army Training Corps at colleges throughout the country to train young men for World War I. The Toledo University Section was housed in a dormitory building constructed on the Scott land on Nebraska Avenue. The building, seen here in the background, later became the Gymnasium when the university moved here in 1922. (Photo by Cull and Howard, 1918.)