Alanson Wood

Alanson Wood

Exhibit Gallery

by Timothy Messer-Kruse

Toledo has had more than its share of inventors. Some are well remembered - Michael Owens, inventor of the automated glass-blowing machine, and Allen DeVilbiss, inventor of the spray atomizer, both of have schools named after them. The fame and fortunes of many of the familiar names of Toledo - Libbey, Miniger, Stranahan, Ross, Spicer, Dana, Doehler, were built on a foundation of technological innovation. All of these inventors are remembered not merely because of the importance of their inventions, but because they managed to build successful businesses upon them. But there are other inventors from this area who are now forgotten, because they were unable to exploit their own ideas. As a society we tend to remember the inventors who were financial successes and forget those who never turned much of a profit.

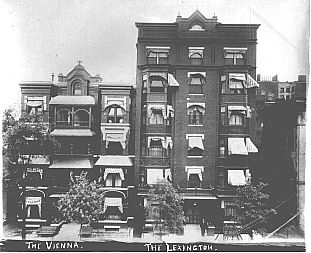

Photograph of the Vienna and Lexington Apartments, circa 1893

Photograph of the Vienna and Lexington Apartments, circa 1893 Photograph of the parking lot on Tenth St., The present day site of the Vienna and Lexington Apartments, February 2000

Photograph of the parking lot on Tenth St., The present day site of the Vienna and Lexington Apartments, February 2000

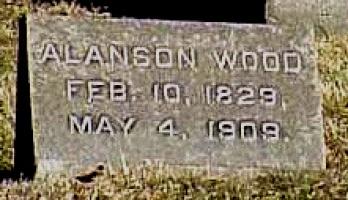

One such inventor was named Alanson Wood. Born in New York State in 1829, Wood settled in Toledo just after the Civil War, where he lived until his death in 1909. Wood, like others of his generation, was a tinkerer and thinker and while he managed to make a modest living from his patents, his success was never sufficient to attach his name to one of his inventions. Though hailed upon his death as an inventor of note and "one of the most interesting characters in Toledo," he was soon forgotten. No books, indexes, or journals devoted to local history contain a single mention of him. He does not even appear in the obituary index of the local library. He had no children to carry on his name. The only trace of his life left nearly a century after his death is his simple tombstone in Woodlawn Cemetery. Even the apartment buildings he constructed with his patent royalties are now just another downtown parking lot.

Alanson Wood deserves better because he was arguably the original inventor of the modern roller coaster.

____________________

The date of the invention of the roller coaster is murky. Contraptions that bore a resemblance to modern-day roller coasters were built in Paris as early as the late eighteenth century. But these were primarily undulating ramps lined with rollers that sent an unwheeled sled on a noisy one-way trip. Various 'inclined railways' were built before the Civil War in America, but these were crude imitations of sluices and chutes - they were all linear and they all began at a high point and ended somewhere far below.

What is undisputed is that the first wheeled ancestor of the modern roller coaster was built along the beach at Coney Island, New York, in 1884. It was the project of another Ohio native, LaMarcus Adna Thompson, who is the man remembered as the father of the roller coaster. This claim is not without merit - over Thompson's lifetime he built dozens of coasters around the country and eventually accumulated close to thirty patents on various coaster technologies. Though he was clearly the promoter who got the coaster craze rolling, Thompson wasn't its inventor.

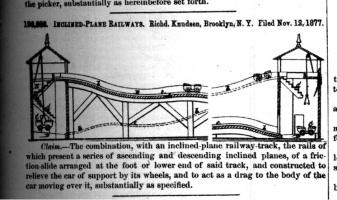

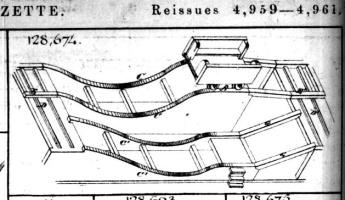

The first roller coaster patent issued in America dates from 1872, when John G. Taylor patented his "Inclined Railway." Like all other roller coasters of the period, Taylor's device was linear - his patentable innovation connecting a pair of parallel tracks with sliding switches that allowed the cars to be reset for another go round.

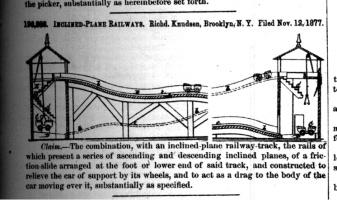

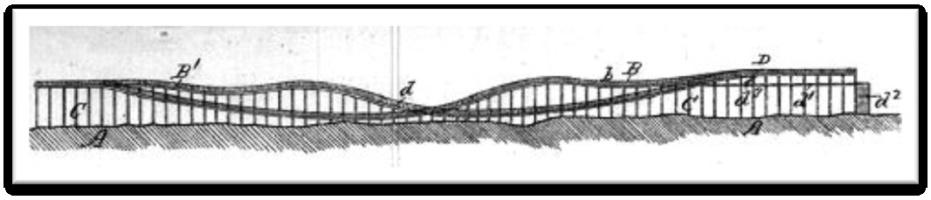

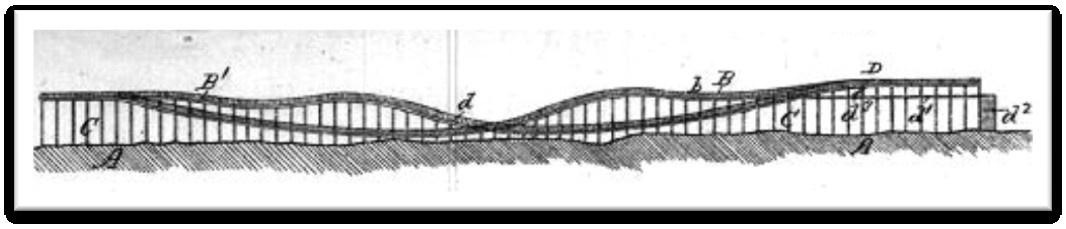

Richard Knudsen's patent for an 'Inclined-Plane Railway' - U.S. Patent #198,888 (Jan. 1, 1878) Source: U.S. Patent Gazette, vol. 13, p. 35Six years later, another inventor, Richard Knudsen, attempted to allow for a greater slope than Taylor's railway did by employing a pulley hoist to reset the cars from track to track.

Richard Knudsen's patent for an 'Inclined-Plane Railway' - U.S. Patent #198,888 (Jan. 1, 1878) Source: U.S. Patent Gazette, vol. 13, p. 35Six years later, another inventor, Richard Knudsen, attempted to allow for a greater slope than Taylor's railway did by employing a pulley hoist to reset the cars from track to track.

John Taylor's patent for an 'Inclined Railway', - U.S. Patent # 128,674 (July 2, 1872)The coaster that LaMarcus Thompson built in Coney Island was essentially of Taylor's design. Because the slope was limited to the incline that attendants could push the cars up, the ride was slow and gentle - about twice walking speed. But this wasn't an inconvenience for Thompson, because he billed his railway as a "scenic" ride along the beach, not a thrill machine.

John Taylor's patent for an 'Inclined Railway', - U.S. Patent # 128,674 (July 2, 1872)The coaster that LaMarcus Thompson built in Coney Island was essentially of Taylor's design. Because the slope was limited to the incline that attendants could push the cars up, the ride was slow and gentle - about twice walking speed. But this wasn't an inconvenience for Thompson, because he billed his railway as a "scenic" ride along the beach, not a thrill machine.

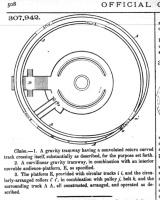

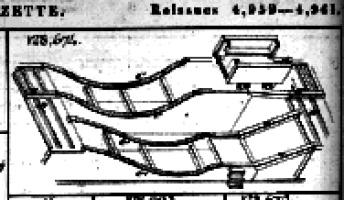

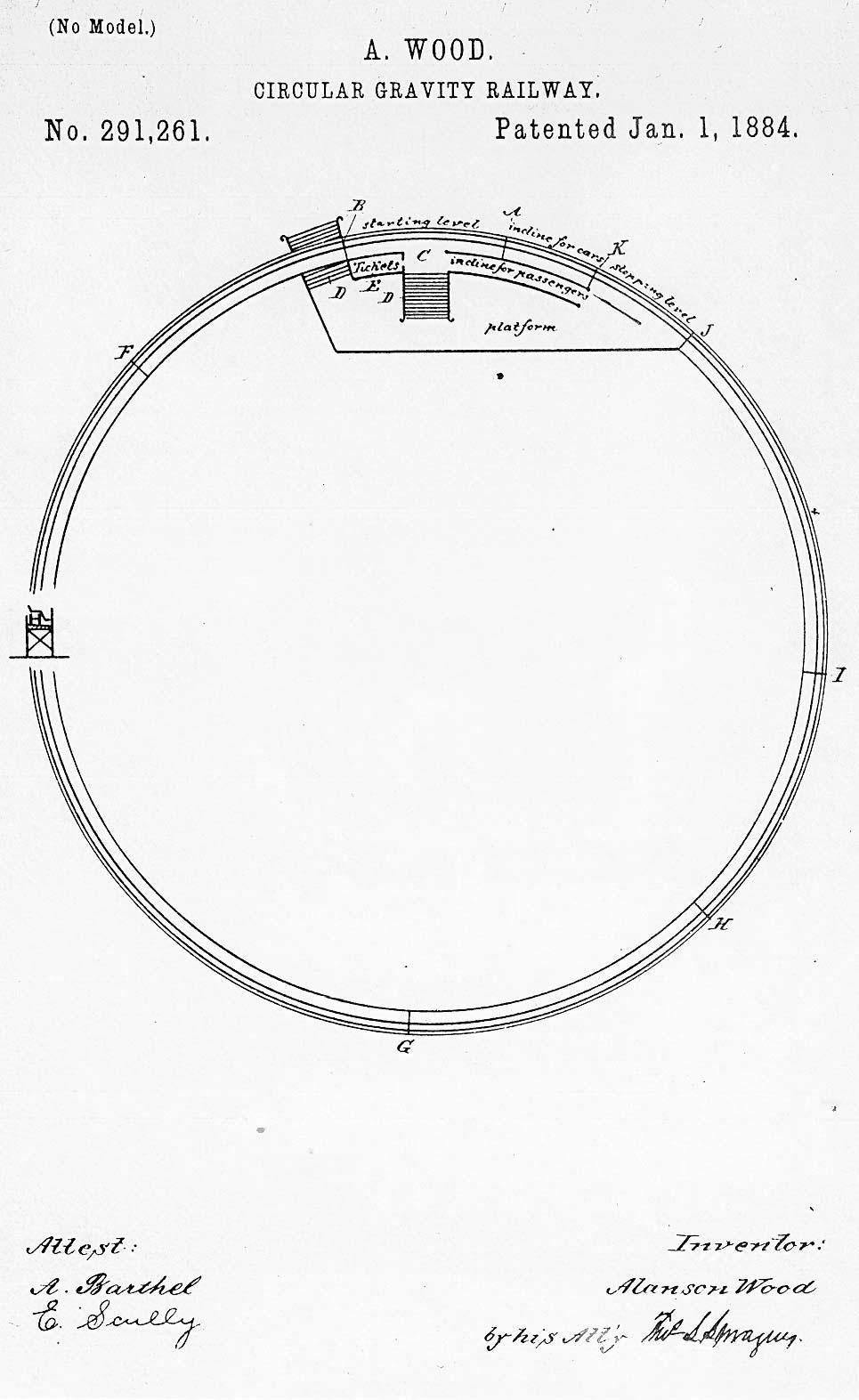

LaMarcus Thompson's patent for his 'Roller Coasting Structure' - U.S. Patent #310,966 (Jan. 20, 1885 - U.S. Patent Gazette, vol. 30, p. 207Before Thompson's so-called "Switchback Railway" was opened, Toledo's Alanson Wood was awarded patent No. 291,261 for his "Circular Gravity-Railway." In his patent, Wood seems to envision not a slow sight-seeing ride, but one intended to thrill. He writes that his invention is designed for cars to "travel by means of different inclines at an increasing rate of speed. . ." Speed seems to be his object: "I find that the level and grades given insure rapid speed in the transit. . ." and "a car traveling on said track will acquire a great velocity...."

LaMarcus Thompson's patent for his 'Roller Coasting Structure' - U.S. Patent #310,966 (Jan. 20, 1885 - U.S. Patent Gazette, vol. 30, p. 207Before Thompson's so-called "Switchback Railway" was opened, Toledo's Alanson Wood was awarded patent No. 291,261 for his "Circular Gravity-Railway." In his patent, Wood seems to envision not a slow sight-seeing ride, but one intended to thrill. He writes that his invention is designed for cars to "travel by means of different inclines at an increasing rate of speed. . ." Speed seems to be his object: "I find that the level and grades given insure rapid speed in the transit. . ." and "a car traveling on said track will acquire a great velocity...."

Wood's patent for a 'Circular Gravity Railway' - U.S. Patent #291,261 (Jan. 1, 1884)

Wood's patent for a 'Circular Gravity Railway' - U.S. Patent #291,261 (Jan. 1, 1884)

Wood's innovation was in conceiving of bending the railway into a circle, eliminating the need for switches, and using a final incline as a brake on the car's momentum, eliminating the friction brakes that were part of earlier patents. His patent also covered an efficient arrangement of ticket booth, stairs, platform, and exit to smoothly accommodate the flow of riders. In sum, Woods' patent covers far more of the elements of the modern roller coaster than any other had before him. Because it covered the concept of a circular gravity railway, it may have allowed him to collect royalties from the actual builders and operators of roller coasters for years to come.

Two years after Wood patented the concept of the circular gravity railway, a promoter by the name of Charles Alcoke built such a ride to compete with Thompson's Switchback Railway at Coney Island.

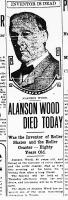

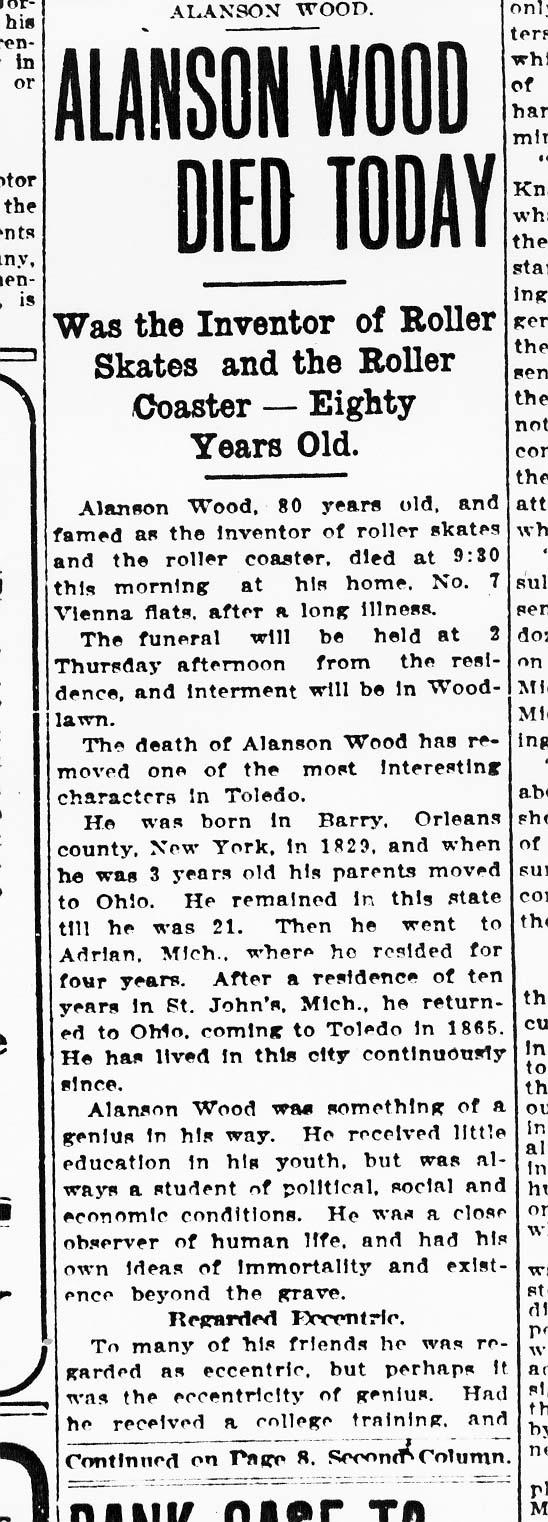

Alanson Wood never built a roller coaster of his own design. His obituary mentions that his opportunities were limited because he never went to college and had "been forced in his youth to bear the privations of pioneer life." Thompson, in contrast, had accumulated a large fortune from the hosiery business before embarking in the business of amusement rides. Nevertheless, Wood apparently realized some income from his invention as his obituary mentions that he sold his patent for a royalty and earned $17,000 in one year.

Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 1

Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 1 Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 2

Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 2 Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 3

Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 3 Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 4

Wood's Obituary from the Toledo Blade, May 4, 1909, page 4

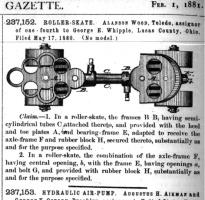

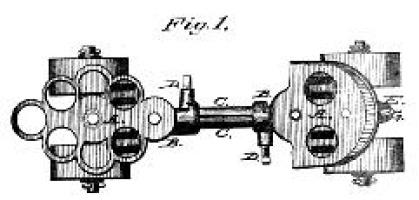

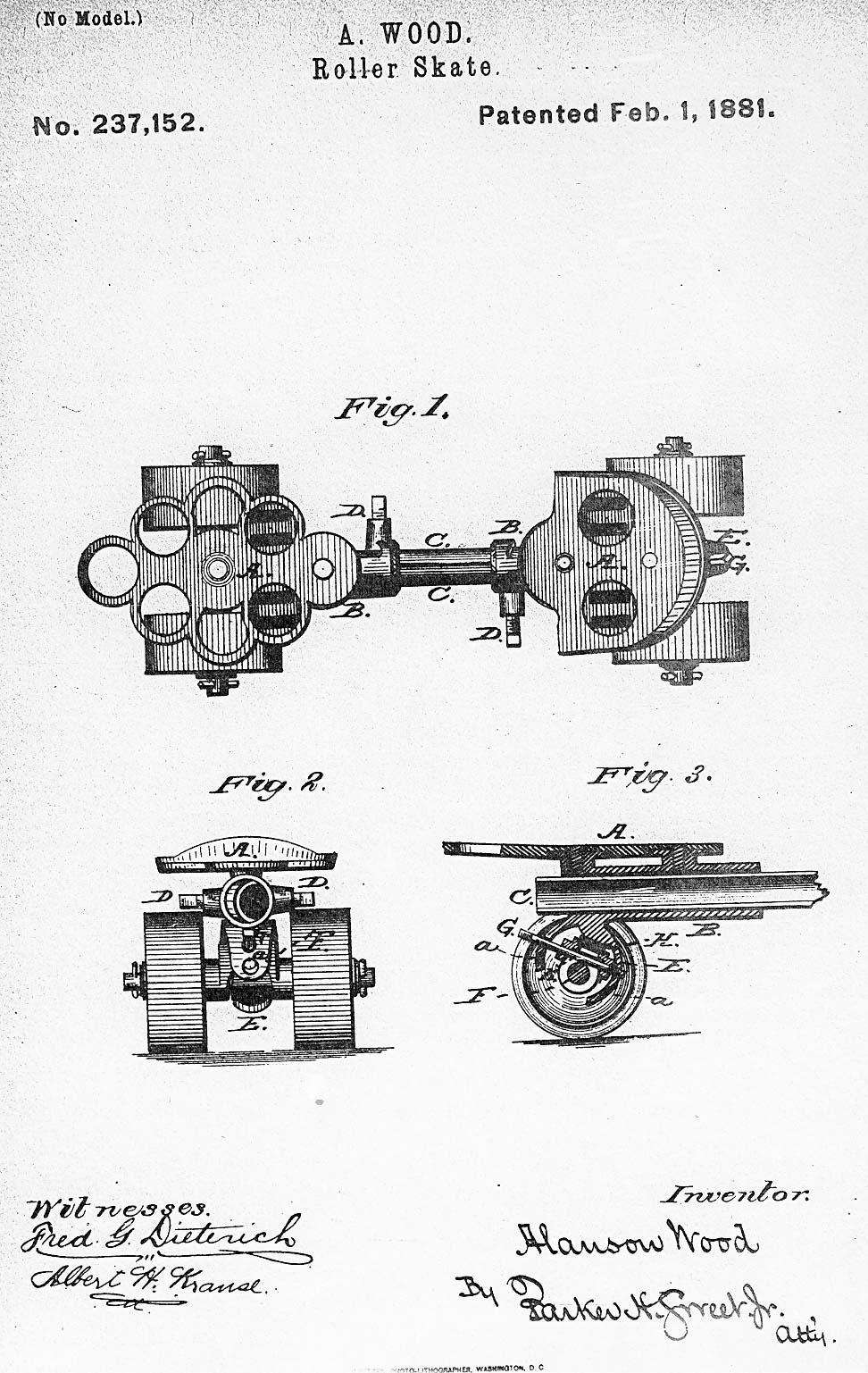

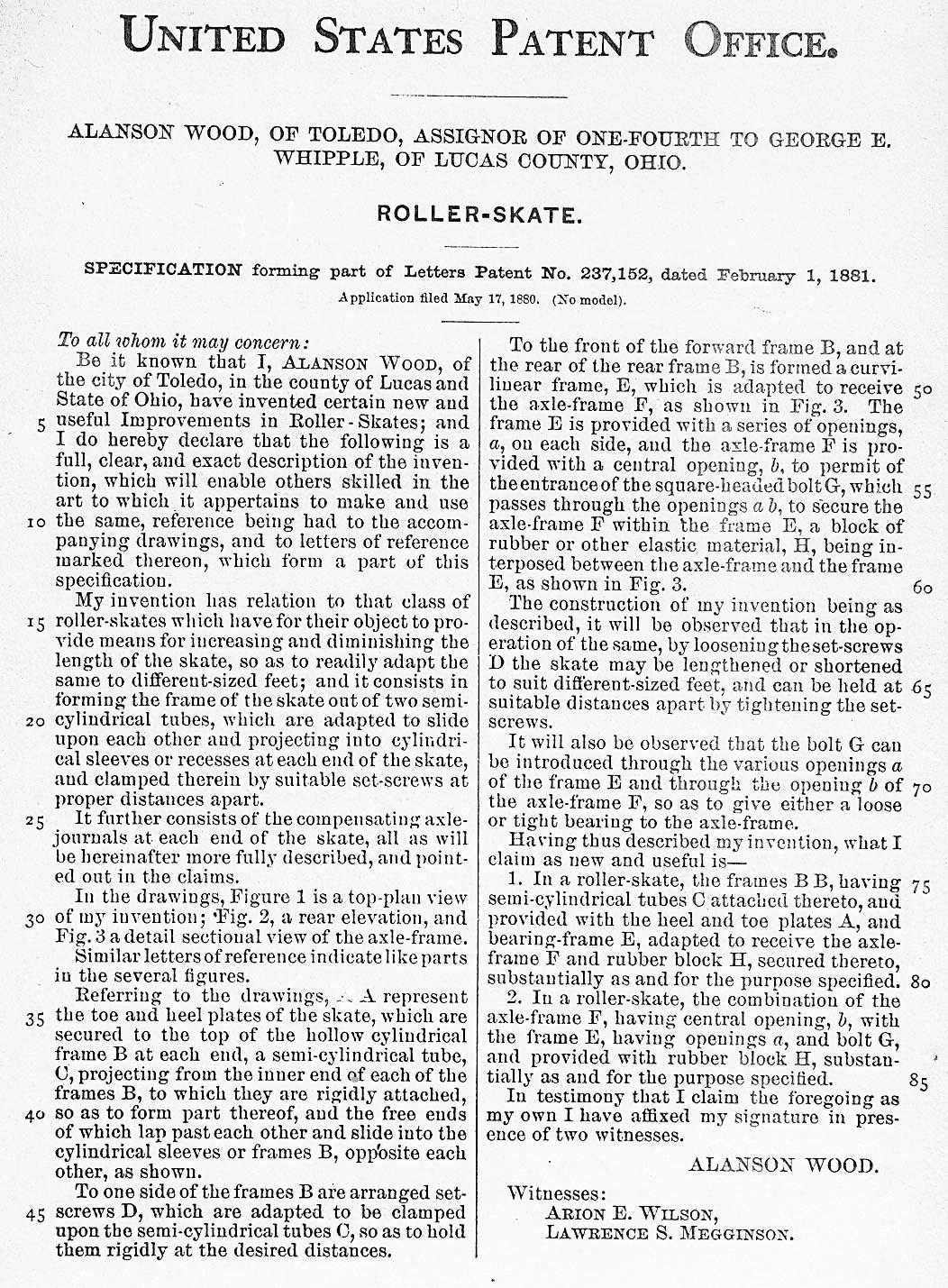

He also realized some income from an improved roller skate he patented in 1881. Wood then seemed to have caught Toledo land fever and invested his nest-egg in a couple of apartment buildings, the Paris Flats on Michigan Avenue and the Vienna and Lexington Flats on Tenth St.

Wood's patent for an improved roller skate - U.S. Patent #237,152 (Feb. 1, 1881)

Wood's patent for an improved roller skate - U.S. Patent #237,152 (Feb. 1, 1881)

Full-text of Wood's patent for an improved roller skate - U.S. Patent #237,152 (Feb. 1, 1881)

Full-text of Wood's patent for an improved roller skate - U.S. Patent #237,152 (Feb. 1, 1881)

Wood's investments never paid off. The Panic of 1893 caught him overextended and his creditors took all his properties in exchange for a lifetime annuity. The inventor's blood still stirred in him, however, and he sold shares in a new venture of his, building the first true airplane. Working out of his "aerodrome" at Madison and Eleventh streets, he worked on a contraption that seems to have been a cross between a helicopter and a parasail. He never finished it, though he did live long enough to hear of the Wright's accomplishments.

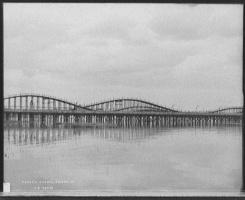

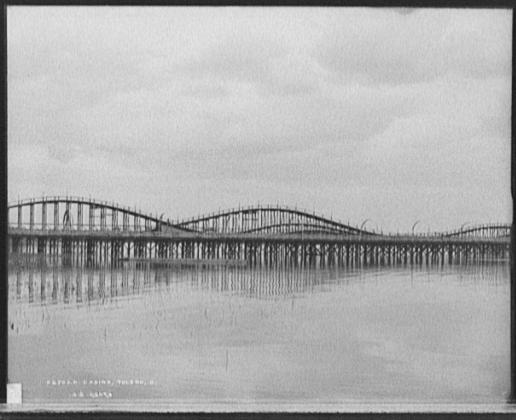

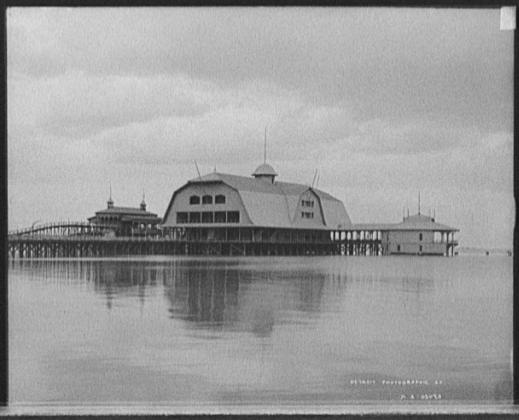

Wood also lived long enough to see the first roller coaster built near Toledo, the Casino coaster at Toledo Beach. Ironically, it was an early linear, double-tracked type, not circular like Wood's invention.

Views of the Casino Amusement Park roller coaster at Toledo Beach (circa 1900-1910)

Views of the Casino Amusement Park roller coaster at Toledo Beach (circa 1900-1910) Views of the Casino Amusement Park roller coaster at Toledo Beach (circa 1900-1910)

Views of the Casino Amusement Park roller coaster at Toledo Beach (circa 1900-1910) Views of the Casino Amusement Park roller coaster at Toledo Beach (circa 1900-1910))

Views of the Casino Amusement Park roller coaster at Toledo Beach (circa 1900-1910))

Source: Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Co. Collection

History should not belong only to the winners, to the men and women who amassed fortunes, whose businesses became growing monuments to their moment of creation. Others, like Alanson Wood, had their flashes of brilliance, their moment of creation, and though they did not ride them to riches and everlasting fame, their achievements deserve our respect.

Bibliography

Al Griffin, "Step Right Up, Folks!", (Chicago: Henry Regnery Co., 1974).

Robert Cartmell, The Incredible Scream Machine: A History of the Roller Coaster (Bowling Green: Bowling Green State University Popular Press, 1987)