Birmingham Days: Life and Times of Toledo's Hungarian Neighborhood

by John F. Ahern, Thomas E. Barden, and Andrew Ludanyi

Introduction

From the beginning, Birmingham's strategic location near the mouth of the Maumee River was attractive to settlers in northwest Ohio. The locale's easy access to Lake Erie, its abundant fresh fish, and its situation under a major migratory bird route made it appealing to Native American tribal groups even before the first Europeans arrived. What was to become the Birmingham neighborhood was inhabited early on by French, German, and Irish farmers who were impressed with the setting's rich, loamy soil. Streets and park names such as Collins, Valentine, and Paine commemorate these early farming settlers.

The shift from agriculture to industry as the primary activity in Birmingham can be attributed specifically to the establishment of a foundry by the National Malleable Castings Company, which transferred a number of Hungarian workers from its home plant in Cleveland to its new East Toledo site on Front Street in 1892. This was the origin of the neighborhood as it is presently known. With approximately two hundred workers moving in, Birmingham quickly became a working-class Hungarian enclave. Their arrival is documented in the registers kept at the Sacred Heart Catholic Church, where many of the first Hungarian settlers recorded their baptisms, marriages, and deaths before St. Stephen's Church was built in 1899. Moreover, this dating of the origin of Birmingham is confirmed in a profile of Hungarian-American communities that was published at the turn of the century by the Cleveland Hungarian daily newspaper Szabadság (Freedom).

Local records show that most of the populace had emigrated from the so-called Palóc counties of North-Central Hungary: Heves, Abauj, and Gömör (now in Slovakia). Most, though far from all, were Roman Catholic. Although assigned to Sacred Heart, a nearby Toledo parish, the newly arrived Cleveland Hungarians were visited regularly by a Hungarian priest from Cleveland, and in 1898 their own parish was established, the Church of St. Stephen King of Hungary. Its registry showed about one hundred families in 1899.

Birmingham's name, like that of the "Irontown" neighborhood just to its north, was meant to invoke a thriving iron and steel manufacturing center, and by the time of the First World War, it did resemble its English namesake, with National Malleable having been joined by United States Malleable; Maumee Malleable Castings; two coal yards; a cement-block manufactory; and the Rail Light Company (later Toledo Edison). The population of East Toledo was growing rapidly, going from 17,935 in the 1900 census to 39,836 in 1920. With this increase came civic amenities such as sidewalks, paved streets, grocery and dry goods stores, banks, bakeries, and saloons. Often, the owners of these establishments lived above the store.

The ethnicity of East Toledo and Birmingham in particular continued as the total population increased. The number of persons of Hungarian birth in East Toledo grew from 647 in 1900 to 3,041 in 1920. The main ethnic group in Birmingham was Hungarian from the beginning, but others were present as well. Immigrant Slovaks, Czechs, Germans, Poles, Bulgarians, and Italians all appear in the WWI-era census records. Like the Hungarians, they lived in modest homes built by real estate speculators. What preservationists would later call "worker cottages" were small one-story houses without basements or indoor plumbing. The backyards were small and front lawns smaller. Some sites had smoke houses, and most kept chickens in fenced-in areas. In time, the privies were torn down and indoor facilities added. At first, most homes were without front porches, but that changed quickly and front porch socializing became an important element of Birmingham life. Gardening occurred in a "green belt" commons area along the railroad tracks that marked the eastern and northern boundary of the neighborhood. Moreover, many Birmingham houses became sources of revenue as families took in boarders, usually single male workers who paid rent to live with established families until they were able to start households of their own.

Until World War I, the major challenge to the first wave of immigrants was adjusting to their new conditions of work, neighborhood, and language. In this adjustment the role of the religious institutions was crucial. Some early organizational efforts came from religious societies, which eventually became the basis for the neighborhood churches. The first important group was the King Matthias Sick and Benevolent Society (Mátyás Király Egylet), which provided the equivalent of social security and disability insurance for members through dues and fundraising. The association split when Catholic members established their own Saint Stephen (Szent István) Roman Catholic Society. This move was followed by the formation of the Saint Michael Society for the Greek Catholics and the John Calvin Society for the Hungarian Reformed Protestants. In terms of community support and fundraising, the Society of Reformed Women and the Saint Elizabeth Roman and Greek Catholic Women's Society were equally important. These groups were the foundation on which the neighborhood's three beautiful churches--Roman Catholic, Greek Catholic, and Calvinist--were built before World War I.

Birmingham got its own neighborhood school early in its history. The first mention of it in the public record comes in 1894 in the annual report of the Toledo Public Schools. The report had this to say: "Near the Craig Shipyard on the east side of the river in a settlement known as Birmingham, a four-room brick building was erected which is now wholly occupied, furnishing ample school facilities for the people of this neighborhood." Early records list Miss Lillian Patterson as the school's principal in 1899 at a salary of $750 a year. The Birmingham School saw numerous additions and by 1916 it was sixteen rooms in size. A gymnasium was added in 1926, which completed the school as it stood until 1962 when it was torn down and replaced by the current structure on Paine Street. Throughout this period of Birmingham's history, the school was a social as well as an educational center, since it was used for public gatherings and adult night classes in reading and writing.

The pre-WWI era also saw the heyday of Birmingham's military marching bands, the first of which was assembled in 1903. John Lengyel and later Julius Bertok were the organizers of these musical ensembles, which served social and ethnic purposes as well as patriotic and musical ones. The most impressive was the Rákóczy Band, named after Prince Francis Rákóczy II, who led the anti-Habsburg rebellion of 1703-1712. The band, which dressed in genuine Hungarian military uniforms, performed in Courthouse Park in Toledo and in Cleveland as part of the dedication of the Louis Kossuth Monument.

Social forces outside of Birmingham were starting to exert influence during this period. The "Americanization Movement," a nativist response to the mass European immigration to Northern industrial cities, was exerting subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, pressure on ethnic communities around the country to abandon distinctive traits and conform to an "Anglo" model. Israel Zangwill's 1908 hit play The Melting Pot notwithstanding, the Americanization Movement urged immigrants to forsake their ethnic identity and abandon 'old country' loyalties. Major pressure in Birmingham came from the Birmingham (Public) School and a citizenship drive that took on a particularly aggressive tone during World War I.

These pressures can be seen in the address Superintendent William B. Guitteau gave in 1916 to mark the opening of the enlarged sixteen-room brick building of the Birmingham School. After comparing the school opening to the launching of a great ship at the Toledo shipyard, Guitteau noted that several men had taken out naturalization papers and several more had enlisted in the Army or Navy, "thereby proving their loyalty to the country of their adoption." He went on to say that "each year brings to us thousands and hundreds of thousands of Germans and Irishmen and Russians and Italians and Hungarians. And yet we have no German-Americans, no Irish-Americans, no Hungarian-Americans. We are all Americans, whether born here or abroad." For the first generation of immigrants in Birmingham (and around the country), this was the constant message: Americanize! And Americanization meant Anglo-conformity. It wasn't until the rise of the idea of multi-cultural identity in the 1960s that this meaning came into question and a more pluralistic conceptualization of society emerged, one that saw America metaphorically more as a tossed salad than a melting pot.

The United States' entry into World War I was an especially trying test of the neighborhood's loyalties. As it was for Germans, this was a difficult time for Hungarian-Americans. Their old homelands were now at war with their new country, forcing them to prove their American patriotism and loyalty. Acquiring citizenship and purchasing Liberty Bonds were two of the easiest ways to do this. A neighborhood businessman named János (John) Strick, for instance, was declared the "first citizen of Toledo" for purchasing $20,000 worth of Liberty Bonds during the war. Commitments to the new homeland were also reinforced by the post-war dismemberment of the historic political units of East-Central Europe. The Austro-Hungarian Empire vanished from the map, and residents of northeastern Hungary found themselves in the southeastern region of the newly created Czechoslovakia. Thus, for many in Birmingham, there was no longer even a homeland to return to. Many residents were convinced that their fate had been decided by the war. Like it or not, they were now destined to become Americans.

The period between the World Wars was one of neighborhood consolidation and psychological adjustment to life in America. Due to changes in U.S. Immigration laws, large-scale immigration came to an end at the same time that post-war realities discouraged the thought of returning to Hungary. A generation was coming into its own that had learned the assimilation lesson and grown up speaking primarily English. Birmingham's secular organizations and the three established churches encouraged neighborhood residents to secure American citizenship, become fluent in English, and get involved in American society and politics. These second-generation Birmingham residents broke into the American mainstream through the professions, business, and politics. The 1920s and 1930s saw the rise of such Hungarian-American owned businesses as Kinsey's (Kigyossy's) Funeral Home, the Weizer-Mesteller's furniture store, and Tony Packo's restaurant.

Birmingham did not escape the effects of The Great Depression, but the neighborhood's cohesion, the support of the churches and social organizations, and the overall spirit of kinship and solidarity saw most of the residents through the hard times. As the interviews in this volume tell repeatedly, people took care of each other, and the community institutions supported their efforts. An example is the way the people cooperated to "liberate" coal from trains coming through Birmingham, with the tacit blessing of the priests.

Two prime movers in sustaining Hungarian consciousness in Birmingham during this period of its history were Monsignor Elemér Eördögh and Dr. Géza Farkas, both of whom are important enough to merit detailed discussion. Elemér Géza Eördögh was born in Kassa, Hungary (now Kosice, Slovakia) on July 4, 1875, into a family tracing its roots to 1232 when it was ennobled by King Andrew II of the House of Árpád. Eördögh received a solid university education, including seminary training at Kalocsa, and was ordained a priest on November 18, 1897 at the age of twenty-two. Initially, he ministered to the needs of a Slovak and German parish in Hungary. He came to the United States in 1911. After a stay in Throop, Pennsylvania, he arrived in Toledo in 1913 and was installed as the pastor of the Magyar parish. From the beginning, Father Eördögh put his heart and soul into his assignment. Though plans for a large new church building had been made before his arrival, he took charge as the actual construction and fund-raising began. From his installation until his death, Father Eördögh provided the church's goals and the strategies to achieve them. Almost all of the present structure was built under his supervision.

After World War I, Father Eördögh's family fell victim to Hungary's dismemberment: his brother and sister were separated by the new international borders. Since he himself associated "home" with upper Hungary, which became part of Czechoslovakia, his commitment to staying in Toledo was surely reinforced. Henceforth he would be a Hungarian-American priest, in spite of his strong links to an aristocratic past in Hungary. His mission became more inextricably intertwined with the fate of the working people of Birmingham. He was still old world upper-class in his personal habits, his ability to "wine and dine" guests, and in the selection of some of his official visitors, which included such luminaries as Countess Bethlen, Otto von Habsburg, and Cardinal Mindszenty.

He saw the parish as his primary concern, but even here his mode of operating was still "old school." He was a hard task-master and a strict disciplinarian, establishing a 9 P.M. curfew for the parish children and managing to keep the youngsters, at least until they were sixteen, out of the local saloons. The force of his personality alone was enough to contain most of his congregation within behavioral limits that he personally defined.

Recognition came from the Toledo city fathers, prominent citizens of Birmingham, the Church hierarchy, and even officials in his former homeland. He became Monsignor Eördögh on November 9, 1929, and received Hungary's second highest award, the Hungarian order of Merit, for his work on behalf of Hungarian-American immigrants. In 1938, he became chairman of the U.S. Hungarian contingent of the International Eucharistic Congress, and in 1939 he was appointed the U.S. Representative to the St. Ladislaus (László) Society of Hungary. Msgr. Eördögh offered his Golden Jubilee Mass on November 16, 1947. But ill health began to take its toll, and in the last eight years of his life assistant pastors took over most of his responsibilities.

The other seminal figure in this period of Birmingham's history was Dr. Géza Farkas, editor and publisher of the Hungarian-American newspaper Toledo, which began publication in 1929. A first-generation immigrant who received his formal education in Hungary, Farkas shared the editing work on the newspaper with his wife Rózsa until her death in 1948. After that he worked alone, often even setting his own type to bring Toledo to its readers. Born in 1878 in the western Hungarian town of Egerszeg in Zala County to upper middle-class parents, Farkas initially saw his vocation as the priesthood, but soon turned to legal studies and received a law degree from Pázmány Péter University in Budapest in 1899. Law did not appeal to him, however, so he started to work for newspapers.

Farkas visited the United States in 1904. He had intended only a brief stay, but settled in Cleveland and within a short time became the city editor of its Magyar Napilap (The Daily Hungarian). He stayed in Cleveland until 1908, when he moved to Toledo. In Toledo he worked for the Imperial Austro- Hungarian Consulate and also started a steamship ticket and foreign exchange agency. Farkas became well known as a major travel agent in Birmingham. He became involved in national politics quickly and served as the Hungarian- American manager of William Howard Taft's 1908 presidential campaign. He acquired American citizenship in 1911.

Between 1908 and 1929, Farkas was an advisor to the Birmingham community in legal, personal, and even family matters. He was an active and public-spirited citizen who helped his people organize churches, fraternal societies, and benefits for the sick and poor. He was also a respected spokesman for the neighborhood and an important link between the Hungarian community and city authorities.

Farkas's many-sided but practical personality is mirrored in the pages of Toledo. It was not a sophisticated paper but a simple weekly concerned with providing working people with useful information. Toledo straddled an important period in the history of Birmingham, the United States, and the world. Beginning publication at the start of the Great Depression, it remained the sole voice of the Toledo Hungarian-American community until the end of 1971. Forty years of history are reflected in its pages, including the perspectives of the editor and the reactions of his readers to such international developments as World War II, the Soviet occupation and communization of Hungary, the Korean conflict, and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. But it also covered events in the civic life of Toledo and Ohio, interweaving them with the day-to-day concerns of the churches, clubs, businesses, and cultural institutions that connected Birmingham's citizenry to the nation and world.

Even though assimilation continued, old Hungarian customs, festivals, and food practices continued in Birmingham during these decades. During this period it was not seen as contradictory to be a fiercely patriotic American while maintaining traditions from the old country. These customs were not practiced in any conscious effort to preserve the Hungarian heritage. They were simply the way one lived life. Summer was greeted by the Corpus Christi procession. Young girls in white dresses and boys in their best clothes marched down the street to pray at highly decorated outdoor altars set up in front of homes. Flowers were scattered on the streets and tree trunks were painted white to make the neighborhood look cleaner. The Harvest Dance was celebrated in autumn when all the backyard and vacant-lot gardens had yielded their crops. Children dressed in traditional costumes and marched behind a band wagon (later a truck) to inform everyone that Harvest Dance was that night. At the dance hall, grapes would be strung from a temporary arbor, and the adults would dance the Csárdás. They would attempt to steal the grapes as they danced, and the children were responsible for arresting the culprits. Everyone was caught, and then they would be brought before the "judge," who would levy a fine. The proceeds always went to a worthy neighborhood cause.

Christmas was not only the celebration of Christ's birth and the occasion for bringing out the best Hungarian food, sweets, and delicacies, but also the time when the Bethlehemes folk play was enacted on the streets, in the bars and neighborhood homes, and finally at midnight Mass on Christmas Eve. The players would collect donations of food, drink, and money from their audiences. [See the appendixes for a translated text of the play.]

The feast of St. Patrick was also a major celebration in Birmingham. While many Toledoans flocked to the local bars to celebrate Ireland's patron saint, March 17th found the people of St. Stephen's participating in a solemn novena honoring the Virgin Mary and celebrating the Hungarians' Irish Madonna. An interesting and little-known story lies behind the celebration. During the English Civil War, the persecution of Catholics in Ireland led many Irish clergymen to escape to mainland Europe. Bishop Lynch was given sanctuary by the Bishop of Györ in Hungary, was made an auxiliary Bishop of that diocese, and eventually died there. After his death, it was reported that a painting he had given to his benefactors was seen to sweat blood for three hours. A copy of the painting was given by the Bishop of Toledo to St. Stephen's Church, and led to the adoption of Ireland's patron saint in a Hungarian parish.

Easter was a tradition-rich time in Birmingham as well. On Palm Sunday, parishioners at St. Stephen's brought pussy willows to church to be blessed as they had done in Hungary, where palms were unavailable. On the Saturday before Easter, baskets of Easter food wrapped in native embroidery were brought to the church to be blessed. The folk art of decorating Easter eggs was practiced. This was a time of jubilation, when the fasting and sacrifices of Lent were over. The climax of the season was the Easter Sunday Mass, but the folk customs continued into the next week. The Monday following Easter was dousing day, a tradition that originated in the villages of Hungary. Originally, the young men would throw buckets of water on the young women, or pick them up and drop them in horse-watering troughs. In Birmingham, the ritual became more stylized and dignified. Young men would ask to sprinkle the young lady of the house, sometimes with a bottle of perfume and sometimes with a homemade concoction. In some cases, they would enter the bedroom and sprinkle the girl before she awoke. But the most common setting, especially among family members, was the breakfast table. For outsiders, including potential or actual boyfriends, the entrance of the house was the customary site. Often the sprinklers would be given coins or Easter eggs. For the younger boys, this custom became an excuse to throw water balloons at the girls. On Tuesday, it was the females' turn to douse. It is said that even the U.S. Mail carriers stayed away from Birmingham on Easter Tuesday.

As is true in most European and American ethnic communities, social rites of passage, like the seasonal events, were centered on the church. Births were marked with baptisms, and young adulthood was recognized by confirmation. The biggest celebrations surrounded weddings. Divorces were extremely rare; marriage was for keeps and for bearing children. Once a marriage was announced, Birmingham watched for male members of the wedding party to walk the neighborhood with a ceremonial cane tied with ribbons proclaiming the event. Some wedding celebrations would last for days. Gypsy orchestras would play and beer and wine would flow freely. Father Eördögh, in fact, confined weddings to the early days of the week so St. Stephen's parishioners would not be suffering from too much celebrating by the time of Sunday Mass.

Funeral rites are well documented in the interviews in this volume. The bells of St. Stephen’s were rung when a member of the congregation died, with one sequence for a man and another for a woman. Between the death and the burial there was a vigil, a time when men stayed in the deceased's home guarding the body in tribute to their lost friend. During the night they would talk of their loss, but they would also play cards, tell stories, and drink beer. After the funeral, especially if the person had been important or affluent, a band would lead the procession to the cemetery.

World War II brought profound changes to Birmingham. Some of these were part of a natural evolutionary cultural process in which the first American-born generation breaks away from the ways of their parents, while their children, reconciled to the past but fully "Americanized," move more smoothly into mainstream, Anglo society. More of Birmingham's citizens began to go through the procedure of naturalization during the war years. In 1941, the year of America's entry into the war after Pearl Harbor, the number of Birmingham residents becoming citizens doubled from the previous year. The numbers remained high throughout the war years. While the old Hungarian traditions did not die out, a marked community reaction against 'old country' ethnic consciousness did set in. This was no doubt due in part to Hungary's status once again as an enemy country, but also by the general groundswell of American patriotism generated by the war. This attitude is apparent in a series of articles in Toledo. They were sponsored by the Common Council for American Unity and designed to give guidelines on raising children who would not be hindered by local, parochial attitudes, but who viewed issues globally. The articles warned against being "hamstrung by ethnic or neighborhood loyalties."

The socioeconomics of the war years also played a part in Birmingham's changes. Young women, housewives, and mothers moved out of the home for the first time to "man" the war industries while their boyfriends and husbands were drafted into the armed forces and were shipped to far-off locales. These experiences re-oriented both groups, giving them connections to different ethnic peer groups in the military and in the workplace. The family and the local community were no longer their only social influences, and a wider view of the world inevitably resulted.

This broadened horizon and the attitudinal changes accompanying it were accelerated by the general technological transformation of American life in the post-war period. Like most Americans, Birmingham residents were moving up and out, and the automobile and the television were the major spurs to the move. Cars were the means by which people could leave their neighborhoods and shop elsewhere, or even move to other parts of the city. This newly found mobility facilitated a migration to the suburbs, particularly to nearby Oregon and Rossford. The June 15, 1945, headline of Toledo proclaimed the departure of one of Birmingham's foremost citizens: "Strick János kiköltözik a magyar negyedünkböl" [John Strick is moving out of our Hungarian neighborhood].

Television's effect was more subtle. Its premiere in the neighborhood was a communal event. Toledo's August 13, 1948, headline read "Television a Monoky-Arvai üzletben" [The Monoky-Arvai bar now boasts a television]. At this juncture, TV was still a novelty and was viewed in a community context. Although TV switched public discourse from Hungarian (or Hunglish) to English, it still brought people in the neighborhood together. Only as television moved into individual homes did its full force begin to be felt in the erosion of Birmingham's sense of community. Television began to replace grandmothers as babysitters and thereby lessened the Hungarian-language link between the generations. It also provided free entertainment at home, which lessened the importance of group activities in the community.

The cumulative effect of the war, mobility, and the rise of a television culture was a decline in Hungarian consciousness in Birmingham between 1945 and 1965. This is apparent in the increasing number of English language articles appearing in Toledo, the extensive coverage given to campaigns such as "Loyalty Day" and "I am an American" celebrations, and the Anglicization of many first and last names. Kigyossy's Funeral Home became Kinsey's. Tony Paczko's Restaurant dropped the "z," becoming Tony Packo's. Another telling example is Toledo's dropping of advertisements for the summer Hungarian language school at St. Stephen's Church. In 1948, the only summer notice was for a New York school offering training in "democratic citizenship."

The gradual fading of ethnic consciousness in Birmingham came to a sudden end with the 1956 Hungarian rebellion against Soviet occupation and repression. Hungarian-Americans, who had twice in the twentieth century been characterized as relatives of "the enemy," overnight became relatives of the fearless freedom fighters who had defied the Communists and fought for democracy against overwhelming odds. In Birmingham, self-effacement was replaced by obvious pride. The community pulled together to support the wave of refugees who escaped and made their way to Toledo after the Soviet Union crushed their revolution. 1956 had a distinct revitalizing effect on Birmingham, even though relatively few Hungarian 1956-ers settled there. Community cooperation was enhanced as the newcomers were greeted and efforts were made to settle them in. Only about 300 individuals came to Toledo, and only approximately one-fourth of them settled directly in Birmingham, but general awareness and pride in ethnicity increased in greater proportions. The infusion provided new leaders for the community, too, since a majority of the refugees were well-educated engineers, businesspeople, and professionals.

This transfusion came at an important moment in the neighborhood's history, since its economic base was beginning to fail. One after another, the major riverfront industries had been closing down. While many of Birmingham's residents were already at retirement age, others were laid off involuntarily as Malleable Casting, Unitcast, and Craig Shipyard closed their doors. For the younger generation, this often meant that they were forced to leave the neighborhood for jobs elsewhere. The process was exacerbated by the red-lining policies of real estate agencies and banks that were eager to sacrifice Birmingham for the newly developing suburbs.

The new leadership and ethnic pride the 1956-ers brought with them, although it had significant impact, was not enough to reverse the overall trend of Birmingham's decline. As the 1960s began, the dissolution of Birmingham as a vital neighborhood was increasingly apparent as the younger generation continued to drift toward the suburbs. A telling indication of the changing times was the renaming of the "Hungarian Reformed Church;" it became the Calvin United Church of Christ in 1962. In explaining the name change the minister said that a new era had arrived in which "nationalistic [sic] labels were becoming less applicable."

It is possible that, despite the influx of 56-ers, Birmingham's slow slide into non-existence might have run its course, as the German ethnic enclave known as Link's Hill had decades earlier. But two events occurred in 1974 that brought Birmingham back from the brink, both as an ethnic community and as a political force in the city of Toledo. The first was the proposed closing of the Birmingham branch of the Toledo Lucas County Library. Birmingham residents organized a group called "Save Our Library" out of the churches and the 20th Ward Democratic Party Club, and, after several reversals, convinced the library board to keep the neighborhood branch open.

The other significant event in 1974 was an attempt by the city planners to widen Consaul Street and build an overpass which would have split Birmingham into two parts. St. Stephen's Father Martin Hernady, Nancy Packo, Oscar Kinsey, and other Birmingham civic leaders organized a response. They mobilized a protest and blocked traffic in front of St. Stephen's church along Consaul Street, the main thoroughfare to the Maumee River. Teachers and their students together streamed out of St. Stephen's school and stopped the cars and trucks. These demonstrations, sympathetic coverage in Toledo's major daily newspaper, The Blade, and some effective lobbying enabled Birmingham to "beat City Hall." Father Hernady, as spokesman for the newly formed "Birmingham Neighborhood Coalition," addressed Toledo City Council and in April convinced the members to postpone the Consaul Street project for ninety days for further study. That summer the issue was voted down unanimously in Council, and The Blade trumpeted, "Residents Triumphant in Birmingham Area." The bells of all three of Birmingham's churches were rung simultaneously for the first time since the end of World War II.

These two civic successes revived Birmingham's sense of community. Furthermore, the energy and political power unleashed by the events had numerous ripple effects. They launched the successful political careers of current Toledo City Councilman Peter Ujvagi and two-term County Commissioner Francis Szollosi. They led to the formation of the Birmingham Neighborhood Coalition and the East Toledo Community Organization (ETCO). They also inaugurated the Birmingham Ethnic Festival, which was originally a victory celebration, but has since become an annual occurrence. Held continually since 1974 on St. Stephen's Day in August, the event is considered one of Toledo's best summer ethnic festivals. Proceeds go to Birmingham's "self-defense fund."

The 1976 presidential campaign brought Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter to Birmingham, a traditional Democratic Party stronghold, where he and Walter Mondale dutifully autographed Tony Packo's Hungarian hot dog buns, in the tradition of the establishment. Packo's was becoming known nationally during this time through frequent mentions by the character Max Clinger on the popular television show "M*A*S*H." In 1977, with a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Birmingham Neighborhood Coalition produced a professional documentary film of the Abauj Bethlehemes Christmas folk play. The neighborhood has also been the subject of a video documentary. Titled "Urban Turf and Ethnic Soul," this video was made in 1985 with support from the Ohio Humanities Council. The Birmingham Cultural Center was established in 1983 through the Urban Affairs Center of The University of Toledo, and over the years has spearheaded numerous projects to collect and preserve the history and culture of the neighborhood. The present volume, in fact, is one of the Cultural Center's projects.

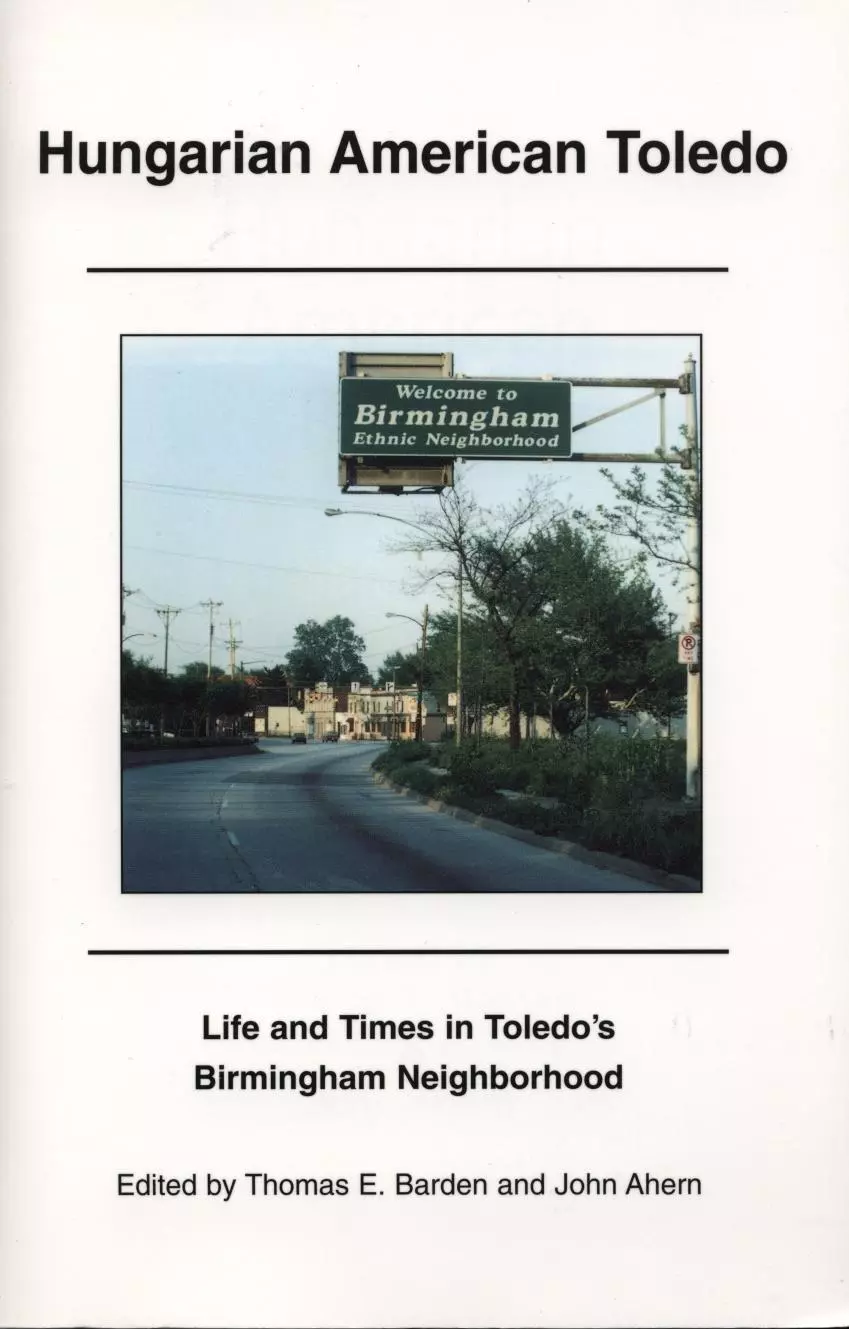

The main effect of Birmingham's revitalization in the 1970s was the rekindling of the idea of Birmingham as a cohesive unit. Birmingham came to be viewed not as a random sprawl of streets and houses with a curious past, but a group entity capable of thinking in terms of "self-defense." It was a community. Today, if you drive into Birmingham from the south along Front Street, you cross an overpass and cloverleaf that shunts traffic on and off of Interstate 280, Toledo's connecting point to Cleveland, Detroit, and Chicago. Over the road, there is a large green highway marker that reads "Welcome to the Birmingham Ethnic Neighborhood." The sign marks the beginning of physical Birmingham, but the actual community is larger than the neighborhood per se. Former Birminghamers return from the suburbs or across the Maumee River on a regular basis--to buy bread at the National Bakery, to get sausage at Takacs' Market [or from Calvin United, which makes traditional Hungarian-style sausage every autumn, winter, and spring], to eat at St. Stephen's chicken paprikash dinners, or to attend church.

In an interview for a documentary videotape, City Councilman Ujvagi, himself a 1956 refugee, commented that there is a large contingent all over the city with an affinity for Birmingham. "Many people have been surprised," he said, "that we have been able to get people who live far, far away--union leaders, teachers, corporate leaders--to come to the rescue of Birmingham. This is because they still come back, to baptize their children, to bury their dead. They may not live in Birmingham anymore, but there is a life-blood in this community that serves not just the people who physically live in it, but involves people throughout the city."

Perhaps it was the arrival of the 1956-ers, or maybe the crises of 1974, or both--but whatever the causes, Birmingham has come to be the most visible and politically powerful ethnic community in Toledo. Writing in 1975, just after the library and Consaul Street civic actions, University of Toledo graduate history student John Hrivnyak commented in his master's thesis that "if the Birmingham community suffered from any serious problem in its history, it [was] a lack of political initiative...Birmingham has never had any of its sons or daughters elected to City Council." Ironically, this was written just as Birmingham was about to elect both a councilman and a county commissioner. Few Toledoans in the 1990s would accuse Birmingham of lacking political clout.

By the time a neighborhood puts up a sign to announce its ethnicity or boasts a large-attendance annual ethnic festival, it may well be that its real period as an ethnic community is over. Tony Packo's pickles, sauces, and sausages are sold from kiosks in suburban malls, suitable for mailing around the country. And a book like this one attempts to capture the special essence of a time and place that no longer exists. But visitors, even in the last few years of the twentieth century, still come away agreeing with the residents, the scholars, and the politicians, that Birmingham remains an extraordinary American neighborhood.

The European immigrant experience in America, of which the Birmingham story is a core example, is receding into memory. Nostalgia for it grips those who lived through it, and, to an extent, all Americans who have lived contemporaneously with it. But nostalgia alone is not enough to keep it from fading. Those with shared experiences and common memory of Birmingham's days must speak of their experiences and bring their memories to life in narrations. And those of us who care about the American experience must take those narratives down and preserve them. The novelist Willa Cather, herself a great documenter of the American immigrant experience, called tradition "the story of a group's experience." The people who speak to you across the pages of this book are the sources of that story for the Birmingham community. As they talk about their lives--their work, play, births, marriages, friendships, deaths, customs and rituals, education, and politics--its tradition emerges. Their voices are the pluribus out of which Birmingham's unum was fashioned over the period of a spectacular and eventful American century.

Explore these resources

Hungarian Sound Records Collection, ca. 1982, MSS-111 (Canaday Center finding aid)

Joseph Bistayi Hungarian Sound Recordings Collection, n.d., MSS-086 (Canaday Center finding aid)

Margaret M. Papp Perry Memorial Hungarian Culture Endowment Collection