Paul Laurence Dunbar and Herbert Woodward Martin

Paul Laurence Dunbar and Herbert Woodward Martin

Exhibit Gallery

Dunbar and Martin: Printed with the Same Ink

By Patrick Cook

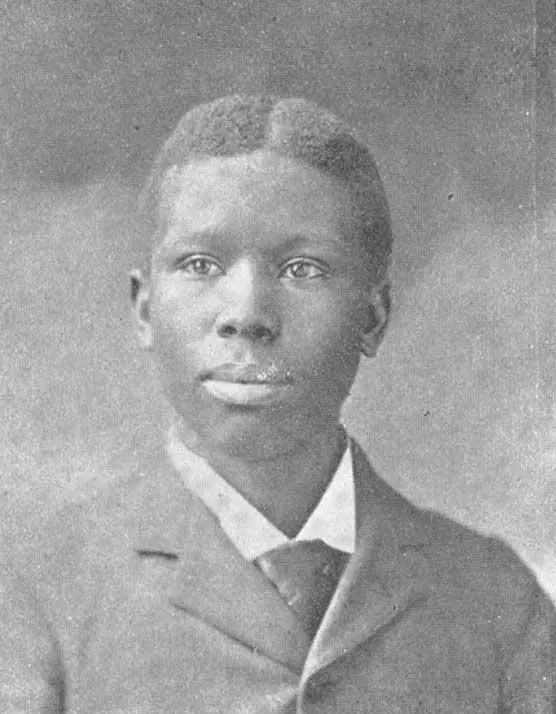

Paul Laurence Dunbar

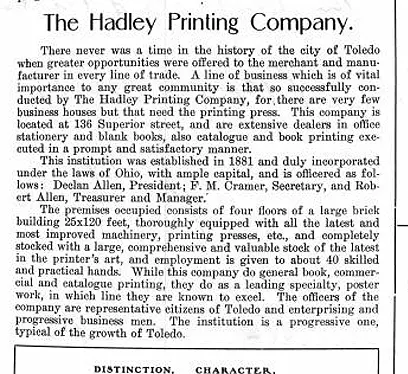

Paul Laurence Dunbar was born in Dayton, Ohio, in 1872 as the son of former slaves. Showing potential from a tender age, Dunbar was the first African American poet to be widely read, especially by the white population, and commented on racial relations at the time through his use of dialect in some poems and traditional writing in others. He was a forerunner in African American writing and set an example for those who would gain success after him. While Dunbar was successful as a novelist, poet, and short story writer, it is his poems that gained him the most acclaim and attention throughout his career. [1] Dunbar performed his first public poetry reading in 1892, and garnered enough success at that time to publish his first book of poems, Oak and Ivy. This collection gained the attention of a Toledo area lawyer, Charles Thatcher, who promoted Dunbar’s work in the area. Through his work in Toledo, Dunbar also met Dr. Henry Tobey, who assisted Thatcher in getting Dunbar’s second book of poetry, Majors and Minors, published in 1895 in Toledo by Hadley & Hadley Printing. In addition to getting his collection published, these individuals also put him into contact with famous progressive Toledoans such as Samuel “Golden Rule” Jones and Brand Whitlock. This second work was positively reviewed by William Dean Howells in Harper’s Weekly, although it favored the works using dialect. It was this review that launched Dunbar to fame and resulted in the wide sales of his later work. [2] Dunbar married Alice Ruth Moore in 1897 and began to experience health problems, though that did not affect his work. He continued to produce poetry, which typically portrayed black life in America and the issues experienced by African Americans. Dunbar and Moore’s marriage was a tumultuous one, resulting in their separation in 1902. Dunbar, suffering from alcoholism and tuberculosis, continued to write and publish his work until his death in 1906.

Though Dunbar has gained criticism for his portrayal of African Americans according to the typical stereotypes of the times, in more recent years his work outside of dialect poems has become increasingly popular and celebrated by modern African American poets and writers. Dunbar was a pioneer for African American writers, and the connections he formed with various patrons in Toledo were crucial to his success and rise to fame.

Herbert Woodward Martin

Herbert Woodward Martin was born in 1933 in Birmingham, Alabama, and moved to Toledo in 1948, where he attended Scott High School and the University of Toledo. Martin’s connection with Paul Laurence Dunbar began at an early age, as his schoolmates teased him for his physical likeness to the poet as they studied Dunbar's works in school. He reconnected with the poet’s work in later years, and went on to become one of the foremost Paul Laurence Dunbar experts in the United States, publishing multiple collections of his work, organizing events to celebrate him, and giving readings of Dunbar's works dressed as the poet himself. [3] Martin established himself as an outstanding poet and writer prior to his work on Dunbar, and became closely interested in Dunbar when he became a professor and poet-in-residence at the University of Dayton, Dunbar’s hometown. He organized the Paul Laurence Dunbar Centennial Celebration in 1972, and continued to gain acclaim not only from his own works which studied African American struggles in his own lifetime, but from his enthusiastic and extensive study of Dunbar’s life and works. He celebrated Dunbar as an inspiration for African American writers and published collections of his unpublished works, contributed to an opera celebrating Dunbar, and organized and produced a video project of him performing Dunbar’s poetry. [4] As a notable alumni of the University of Toledo, celebrated as an actor, singer, poet, and writer, Martin has been honored by the University on multiple occasions and has been nominated for several alumni awards and honors.

Visit the Ward M. Canaday Center's Finding Aid MSS-015, 095 to discover their collection of original material (both academic and creative) written by Martin, as well as interviews and more.

You can also see the 2004 Kent State University Press publication Herbert Woodward Martin and the African American Tradition in Poetry by Ronald Primeau, a longtime friend of Martin's, which can be found in the Finding Aid MSS-015, 095.

Paul Laurence Dunbar Partnering with Herbert Woodward Martin

Doctor Herbert Woodward Martin, a renowned scholar on Paul Laurence Dunbar, has become known for reciting Dunbar’s poems in ways that Martin believes they would have been performed at Dunbar's own performances. [5] The important function of these readings is to allow the listener or reader of Dunbar’s work to get a better grasp on the cadence of a poem written in a dialect style, to better allow for contrasting those dialect poems with those written in a more traditional style. The dialect poetry of Dunbar was by no means Dunbar’s sole writing style, though they did gain him a great measure of his popularity and financial success.

The Hadley Printing Company Advertisement

The Hadley Printing Company Advertisement

Dr. Herbert Woodward Martin unearthed plenty of evidence of Dunbar’s attempts to become renown for more, especially in the discovery of an unpublished play titled Herrick which had no African-American characters and also seemed to make use primarily of the English dramatic style. Martin believed that Dunbar wrote the play as a means of displaying his mastery over many forms of the English language, not just the dialect of those from the antebellum south. Dunbar did live in England for a time, before returning to America and marrying his wife, therefore it only makes sense that he would have first-hand experience with yet another way of speaking English. [7] It was as though he was attempting to master the language for better compositions in his written work as a songwriter might master different genres of music for better musical compositions.

While Dunbar gained popularity as a poet, he also wrote short stories, novels, and plays. Dr. Martin, on the other hand, seems to have primarily written poetry, aside from critical academic works in his field. Martin’s poetry can vary greatly, though he does little work in dialect poetry. Martin gains publicity for his poems by reciting them after a performance as Dunbar, as well as readings devoted to his own work. Martin states that he and Dunbar have an understanding; after Martin performs Dunbar’s work to bring him a little fame, Martin performs his own work so that they can both prosper a little. [5]

While Martin writes in the modern style, he primarily connects his poetry with Dunbar’s by attempting to capture a sort of lyricism or melody in his work. Martin often sees this inspiration by song in Dunbar’s poetry, even pairing selections of folk or hymnal music in his performances of Dunbar’s poetry. He feels this helps to bring out that lyrical quality that the poem contains, or may have been inspired by. [8]

Martin, as a scholar, puts a great amount of thought into his poetry. He is also adept at articulating the meaning behind his poetry, which limits some of the conjecture that usually surrounds the interpretation of such artistry. It is one of the advantages of a living poet like Herbert Martin when compared to a deceased poet like Paul Dunbar.

You can listen to Herbert Woodward Martin perform various works by Paul Laurence Dunbar and others here.*

"My Mother's Voice" by Herbert Woodward Martin and "An Easy-Goin' Feller" by Paul Laurence Dunbar both exercise a dialect style. But more than that, they also center on easily discernible advisory themes.

A side by side comparison of the two poem.

|

An Easy-Goin' Feller by Paul Laurence Dunbar THER' ain't no use in all this strife, See Martin perform "An Easy-Goin' Feller" by Dunbar on YouTube.*

|

My Mother's Voice by Herbert Woodward Martin (Transcribed from a Canaday Center Audio Cassette) [9] Lord child, I done told you a million times Listen to Martin's performance of "My Mother's Voice"

(digitally published with the permission of Dr. Herbert W. Martin) [9] |

These two poems seem to connect rather well, because the message of advice is so parallel between the two speakers. Beginning with Paul Laurence Dunbar's "An Easy-Goin' Feller," the reader is given the image of a speaker that is content to take life easy, even though that means being somewhat on the level of a vagabond. The speaker only wants to work enough to eat and otherwise wants to be left alone, and he is trying to convey to the reader that this is the way to live life; a simple person with simple tastes. This poem is also an excellent example of Dunbar's connection to music, as it contains a reference in the line "limber up my soul with song," suggesting the power of it is able to lift even this speaker to something other than mellow mediocrity, even if it is only temporary.

The message in "An Easy-Goin' Feller" also seems to almost directly contradict Dunbar's lifestyle, as he wasn't content with doing only enough to get by. As we know, he worked hard to become a self-made individual, and continued to work at bettering his craft right up to his early death from tuberculosis. It seems as though Dunbar was capturing the voice of some of his peers of the era and their willingness to avoid any difficulties by isolating themselves from the public majority. As the speaker states "Ther' ain't no use in all this strife / An' hurryin', pell-mell, right thro' life," suggesting that the speaker would rather stagnate and live slowly rather than trying to make real progress and improve himself.

As for Herbert Woodward Martin's "My Mother's Voice", the reader is again approached with a speaker trying to give advice. In this poem, it is the voice of a mother speaking to her child who is trying to become a poet, as Martin did. This poem, however, is a bit more humorous than Dunbar's, because the speaker is willing to admit by the end that her generation has made plenty of mistakes by saying "Lord, Lord, these children are gonna be the death of us all. / Not that we ain't givin' 'em plenty of kindlin' wood." This token has another side as well, by the speaker subtly telling the reader that the previous generation doesn't really know how to advise the next, it implies that their advice perhaps isn't valid and their way of doing things should fade with them.

It also illustrates that the speaker doesn't really understand the drive behind authorship as a way of building a legacy and gaining a measure of renown. The speaker doesn't even understand the desire for it, "Attention ain't no good when you're dead. It don't make no sense." It is something like the speaker of "An Easy-Goin' Feller"'s desire to keep a simple and low impact lifestyle to avoid conflict. Both of these speaker's don't want to have a success which the authors managed to gain. They don't want to understand the drive that people like the authors have that causes them to work for something great, and not worrying about whether or not they will succeed financially. As in "My Mother's Voice", "If you ain't got no money, you ain't got nothin' to say", seems to be the attitude of both of the speakers while being inconsequential to the authors themselves.

In both cases, we see that the authors Martin and Dunbar are expressing the voices of their opposers, or if not in opposition, the voices of those without ambition. Whether or not these are based on real encounters that these authors had is fairly difficult to tell. All we know of Martin's poem is his slight introduction to the piece by stating that he talked to his mother about it, and she commented, asking if that poem was supposed to based on her. It doesn't necessarily mean that it summarizes the thoughts of the author's actual mother, but it does imply that there is a basis for the content in reality.

It is clear that Paul Laurence Dunbar and Herbert Woodward Martin are important for essentially the same reason: They are artists that use the medium of words to convey themselves. They are both authors that have important impact and influence on writing, and in this case specifically, writing with cultural content. They make use of their experiences and imaginations to gain insights into the human experience. This also lends to Martin's academic pursuits of the topic as not only important from a literary standpoint, but from an anthropological one as well. This leads me to believe that these two authors, while separated from each other by time, are very similar in their valuable contributions to a cultural heritage for future generations to reflect upon. They have both laid the groundwork for future artists to imitate and build upon as Martin has done with his predecessor of Dunbar.

If you would like to hear more about the life of Martin and his interests in poetry and academics, a biographical film can be found here, which offers a video of Martin's early performances as well as a free trailer for the film.*

If you would like to read Paul Laurence Dunbar's poetry, his entire collection can be found as a free e-book under the public domain at Google Books, Project Gutenberg, and as a kindle edition at Amazon.*

Herbert Woodward Martin's poetry or academic works can be purchased on Amazon or at select bookstores.*

Physical materials can also be found in the Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections, the specific collection's contents for Herbert Woodward Martin's papers are MSS-015, 095.

*These links are to external websites not under the domain of Toledo's Attic. As such, we cannot be held responsible for the maintenance or content of these sites. Concerns over external website material should be directed to their respective owners, unless a link is broken.

Bibliography

[1] Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 6: Paul Laurence Dunbar." PAL: Perspectives in American Literature- A Research and Reference Guide. URL:http://www.csustan.edu/english/reuben/pal/chap6/dunbar.html (January 20,2012).

[2] “Paul Laurence Dunbar Biography: 1872-1906.Poetry Foundation. URL http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/ paul-laurence-dunbar. (January 20, 2012).

[3] Murphy, Maureen. “Action Profile: Herbert Woodward Martin.” University of Dayton Campus Report. February 10, 1989: [no page number].

[4] Rizvi, Teri. “A Poet and His Song.” University of Dayton. URL http://www.dunbarsite.org/rizvi.asp. (January 28, 2013).

[5] Stephen Burd. "A Poet Gives Life to His Fascination." Chronicle of Higher Education. URL http://www.dunbarsite.org/chigher.asp. (February 7, 2013).

[7] Ronald Primeau. "Herbert Woodward Martin and the African American Tradition in Poetry." page 154.

[8] Ronald Primeau. "Herbert Woodward Martin and the African American Tradition in Poetry." page 168.

[9] Herbert Woodward Martin Papers. MSS-015, 095. Papers II. Box 3, Folder 5. Cassette: College Reading Side 1. Time Marker 362.