Inside Hines' Farm Blues Club

Inside Hines' Farm Blues Club

Exhibit Gallery

Credits: Prof. Thomas Barden for the donated photographs in this collection.

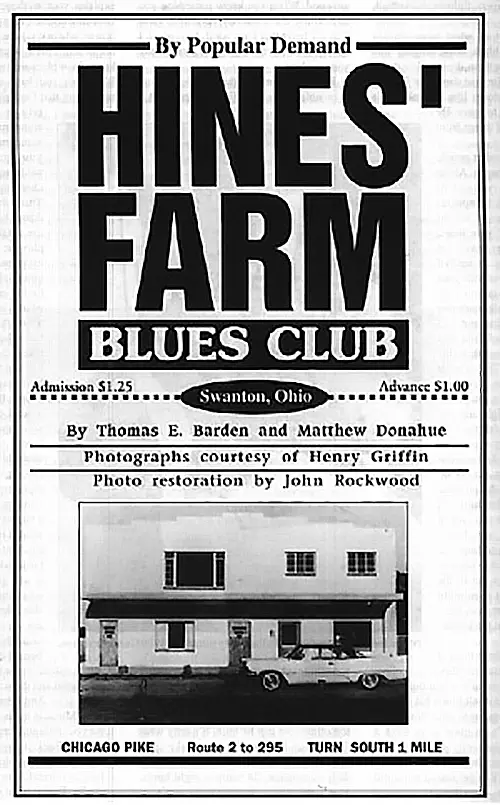

Hines' Farm Blues Club

by Thomas E. Barden and Matthew Donahue

The whole thing started in Frank and Sarah Hines' basement. By the time they built the club itself in 1957, Hines' Farm was already in full swing as a blues center. They had received a state liquor license in the late '40s when they were still operating out of the basement; in fact, they were the first African Americans in Northwest Ohio to have one. Blind Bobby Smith, a Toledo blues guitarist who did session work in the '60s for Stax Records, used to play in their basement in those days. He remembers how the party would start outside, but "after they'd close down outdoors we'd all pile in the basement. In the wintertime he [Frank Hines] just ran it out of the house. It was, you know, everybody talkin' at the same time...passing the bottle around, and Hines wishin' everybody'd get out of there so he could go to bed."

The first real club spot once they moved out of the basement was a shack in the woods at the back of the Hines' property. They built this in 1950. A neighbor who lived across the road said, "Man, it was good to go back there in the woods. See, I never took my car. I'd just walk back there and have me a cold beer and watch 'em dance. See, that place back there, they used to dance. Chicks would come out of Toledo. Some of them ol' gals was good lookin'. I'd sit there and drink beer and watch 'em from mid-afternoon. Hell, I wouldn't leave 'til dark...watchin' them chicks shake it up."

Ordinarily, Frank Hines was the bouncer and keeper of the peace. Henry Griffin, the current owner of the property, was a kid in the '50s, when the shack was the center of the Hines' Farm scene. He remembers that Hines would check everybody for knives and guns and just take them. He would give them back when they left. But he wouldn't let any trouble start. And neither would his wife Sarah. "One time Sarah broke a beer over a guy's head. He got out there and played like he was drunk and was sayin' a lot of filthy talk in front of the women, and she tried to get him to hush, you know, and he wouldn't do it. So she went to him a couple of times. The third time, he started all kinds of that filthy talk, and she just took a beer bottle and went up there and hit that son-of-a-bitch on top of his head. That damned bottle shattered all to pieces, man, and that guy said, 'She tried to kill me.' He grabbed his head and said, 'She killed me. I'm gonna tell Sonny'-that's what everybody called Frank Hines. She said, ‘I don't give a damn if you tell Sonny-just get the hell out of here.’ And it was peaceful the rest of the night."

The shack was full-service. It had electricity for amplifiers and lights, and a kitchen with a barbecue pit that could handle two full hogs. They served catfish and chicken, too. There was a beer bar and a stage and lights strung off into the woods. They even built a home-made, nine-hole miniature golf course in the woods beside the shack. Altogether, it could accommodate over a hundred customers and keep them entertained night and day.

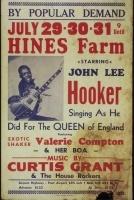

But the shack alone wasn't enough to handle the crowds the Hines were attracting. And it became clear by the mid-50s that they needed a bigger place. Frank's brother George Hines, who had run a night club in St. Louis, helped him with the planning and construction of the main club building that, according to Henry Griffin, was built in a year and was finished and ready for business by the summer of 1958. Sarah ran the bar and restaurant and booked the bands. According to Big Jack Reynolds, one of the regular performers in the club’s early days, "she worked herself to death." Reynolds recalls that the main bar area "could fit 500 people. She had seven waitresses runnin', two cooks runnin', you could go out there to get breakfast. We [Reynolds' band] were from Detroit, we could eat breakfast and if you got sleepy you could go upstairs." There were rooms with bunks above the bar for out-of-town musicians. John Lee Hooker, another one of the Hines' Farm regulars in those days, would come down from Detroit and stay in one of the upstairs rooms. In fact, Hooker actually lived at the Hines' Farm club for two summers.

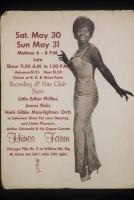

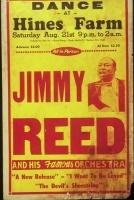

John Lee Hooker is not the only famous blues artist that played Hines' Farm in the '50s. "All the big timers were there," says Roman Griswold, a Toledo bluesman who, with his brother Art Griswold, opened for many of the big-name acts. "They had B.B. King, Freddy King, Jimmy McCracklin, Bobby "Blue" Bland, Little Esther Phillips, Jimmy Ricks." These name musicians made a big impression on the Griswold Brothers. Art recalls the night John Lee Hooker came from Detroit and sat in the B.B. King-"and that was a knockout." He says, "One thing about playing at Hines', though, you had to be a pretty damn good musician 'cause he wanted the best."

Roman remembers one night when Freddy King played. "Hines told the drummer, "When you go back up, tell Freddy King to turn that music down. It's too loud,' he said, 'they can hear you way out on Airport Highway.' And he [Freddy King] got on the microphone and said, "Sonny Hines, they can all hear me on Airport Highway now and I'm gonna turn it up and they're gonna hear me in Toledo now.'"

Even after they had the indoor club and stage, they still played outside in the summer months. Some nights, in good weather, the shack would go on concurrently with the indoor acts, and the musicians playing back there could really turn up the volume. Henry Griffin recalls that "they was out in those woods, and they'd say, 'We're gonna open up the woods tonight.' And it was like that Mississippi stuff, when they go in the woods, that's when they gonna party in the woods." He adds that the music could be heard across the swamp and that's how people would know Hines' Farm was starting up. "You wouldn't even have to advertise, you could hear the music everywhere the blacks stayed."

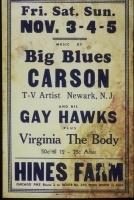

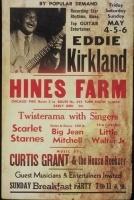

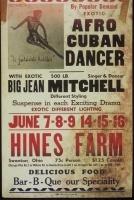

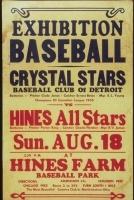

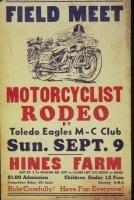

Whether they needed to or not, Frank and Sarah Hines did advertise. They placed posters and flyers, put ads in the local black newspapers, and even drove around the black neighborhoods of Toledo with a sound car. Art Griswold describes it this way: "Sarah Hines had a car with a speaker on top of it. She would drive through town and say what was going on." And what was going on was amazing. The ads in The Bronze Raven, a black arts and entertainment sheet that published from 1951 to 1973, show that Hines' Farm hosted a virtual who's who of African-American performing artists, from the big-name people and national-level acts like the Falcons and the Bill Doggett Band to such second-level acts as Big Blues Carson; Eddie Kirkland; Little Walter, Jr.; Betty Lovett; Johnny Mae Mathews; and Chiquita, the Girl Drummer.

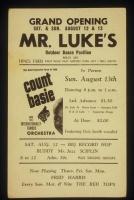

While most of the performers were blues or rhythm and blues musicians, some jazz greats also played Hines' Farm. Local jazzmen like Eddie Abramms were joined by such famous jazz artists as Louis Jordan and Count Basie. Basie and his full orchestra were booked for the grand opening of an outdoor pavilion that was built adjacent to the club building in 1961. The pavilion, which doubled as a roller rink and dance floor, could handle 1,500 people. Hines constructed the stage at the far end of the pavilion so performances could go on there while another group was playing inside. "Outside was great, music under the stars they called it," says Roman Griswold. "All you had to do was kill a few mosquitoes and keep doing what you was doing."

Big Jack Reynolds remembers the outside stage very well too. "Well, I had all my people there, my brother and everything from Detroit, and I got up on the stage and the whiskey told me that I could turn a flip like them other guys. [Reynolds weighed well over 250 pounds at the time]. Now, I'd never turned a flip in my life. But I jumped and said 'I'm gonna blow this sucker [his harmonica]. 'I was blowin' and they was all pullin' for me and I says, 'Shit, I can do it.' to myself. Man, I jumped up and flipped over and come right down on my neck. Goddurn, I'm layin' down there kickin' and they say, 'Look at that sucker blow that harmonica.'"

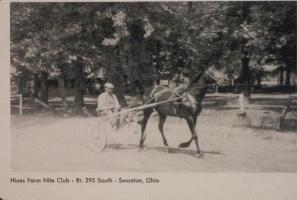

Music was the main thing at Hines' Farm, but it wasn't the only thing. One reason why Henry Griffin bought Hines' Farm after the Hines' death was his memories of all that went on there when he was a boy in the early '50s. He remembers getting hayrides around the property while his parents were dancing back at the shack. There was also roller skating, amusement park rides, exhibition baseball games, horse races, hobo car races, squirrel hunts, and-the one event everybody remembers about Hines' Farm-motorcycle races. Griffin recalls that the motorcycle races were really impressive. "Hines would send out a flyer that he was havin' a motorcycle race and he would have people come from Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and they'd get on their motorcycles and ride right up there. And there'd be thousands of 'em."

There was entertainment besides the music inside, too. There were comedy acts (such as the Boll Weevil), female impersonators, and numerous shake-dancers. In was a black club, but it wasn't segregated in any sense of the word. Big Jack Reynolds says that Mexicans and whites were welcome, too: "there was no discrimination there." And Griffin recalls that the migrant tomato pickers would come in the late summer when they were workin' northern Ohio, "and they'd be welcome too." Also, some groups of gypsies that passed through northwest Ohio had a deal with Hines. He would let them stay on the property, and he even provided them with an old school bus at the edge of a field to store their belongings out of the rain when they set up camp. In exchange, they worked for him on the farm.

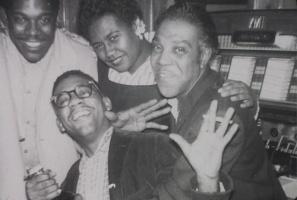

Frank and Sarah Hines

When they were unable to maintain the club, they leased it out to managers, and it went through several of these manager arrangements in the early '70s. Their own children weren't interested in taking it over and by the fall of 1976, Hines' Farm shut down. Roman Griswold went to see Sarah Hines at the Farm in 1978 just before she died. "I remember what she said then. She said, 'You know, I tried to do the best I could for this place. I tried to get the best entertainment I could find. And I liked it. And I don't regret a day." Frank Hines died three years later in 1981.

Hines Farm was the undisputed center of the blues scene in northwest Ohio. It thrived for 20 years on the outskirts of Toledo in the predominantly black rural area called Spencer-Sharples near the little town of Swanton, Ohio. Frank and Sarah Hines imagined it, created it, and maintained it all that time as one of the major stops on the chittlin circuit. In doing so, they provided one area of the Midwest with some of its very best blues and all around good times.

Before his retirement, Thomas E. Barden had directed the American Studies program and taught English at the University of Toledo. His book, Virginia Folk Legends, was published by The University Press of Virginia in 1991. Matthew Donahue was a graduate student in American Studies at Bowling Green State University at the time and lead singer in the rock group Head. (Reproduced with permission of the author from Living Blues No. 103, May/June 1992, pp. 30-37.)