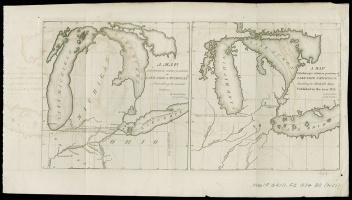

Michigan and Ohio borders in 1830 and 1755

Michigan and Ohio borders in 1830 and 1755

Exhibit Gallery

Introduction

This little known but very important "war" shaped the borders of the states of Michigan and Ohio, with the final outcome granting Toledo, MI and what is now the upper corner of Northwest Ohio to Ohio. Michigan did not leave empty handed, however – the then-territory was granted what is now known as the Upper Peninsula of the state.

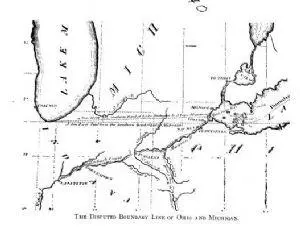

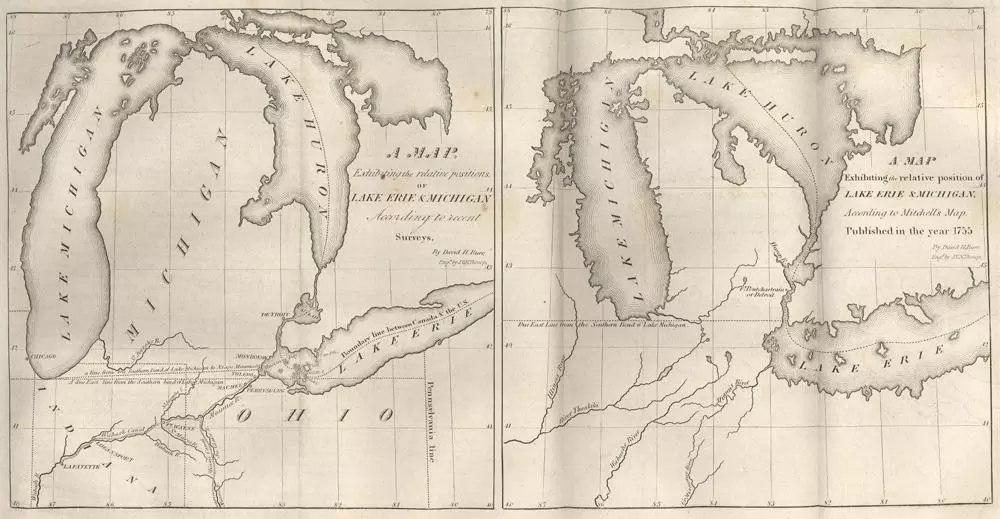

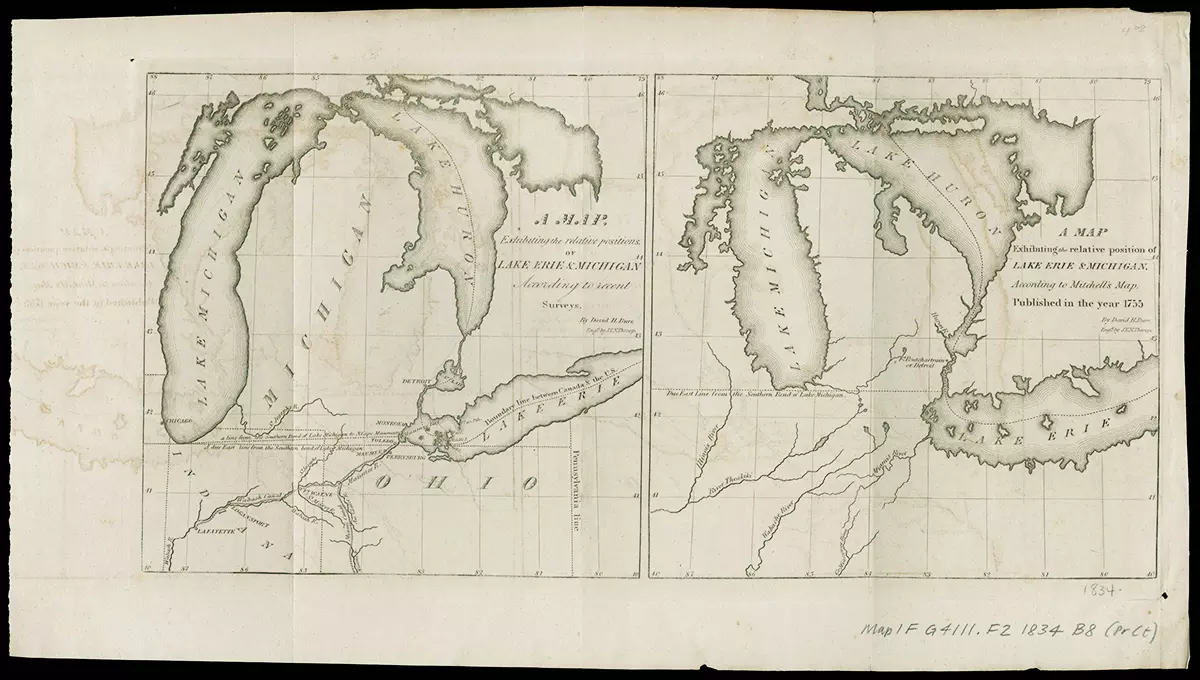

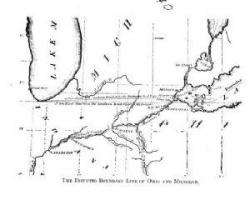

The disputed boundary line of Ohio and Michigan: on the right is a comparison of maps by Michell (1755) and Burr (1830)

The Original Ohio and Michigan Borders

Mitchell's map showing the Ohio border after the passing of the Northwest Ordinance

Mitchell's map showing the Ohio border after the passing of the Northwest Ordinance

In 1787, the young United States began expanding westward, with the passing of the Northwest Ordinance resulting in the creation of the Northwest Territory. Based on this new legislation, five states were slated to be created in the new territory: the present-day states of Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin (the region also included part of what is now Minnesota). All were to be non-slave-holding states.

As the Territory of Ohio prepared to join the United States, borders for the new state had to be drawn up. In 1802, Congress drafted the borders for the future state. In accordance with the Northwest Ordinance, the northern border of Ohio was to be a line that could be drawn due east from the southernmost point of Lake Michigan.

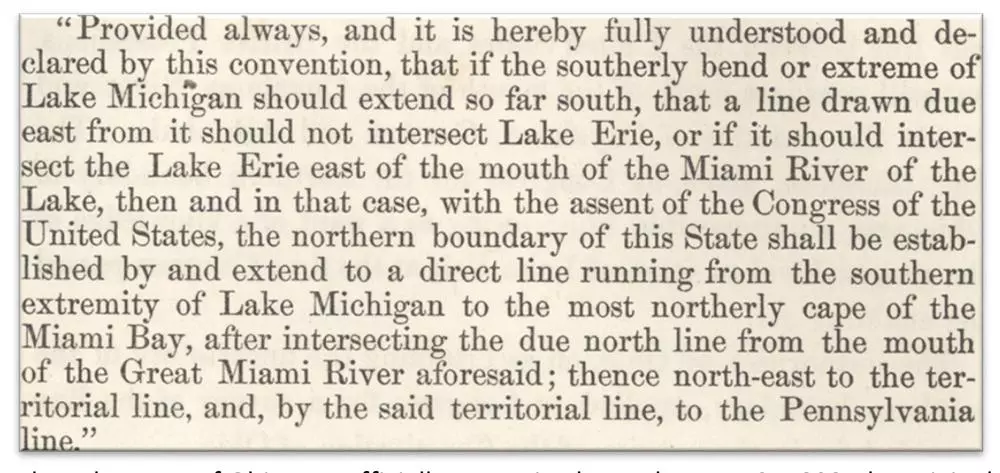

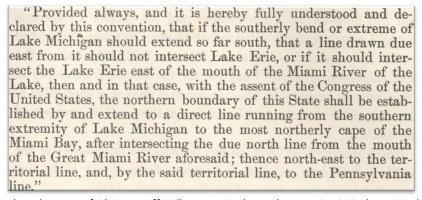

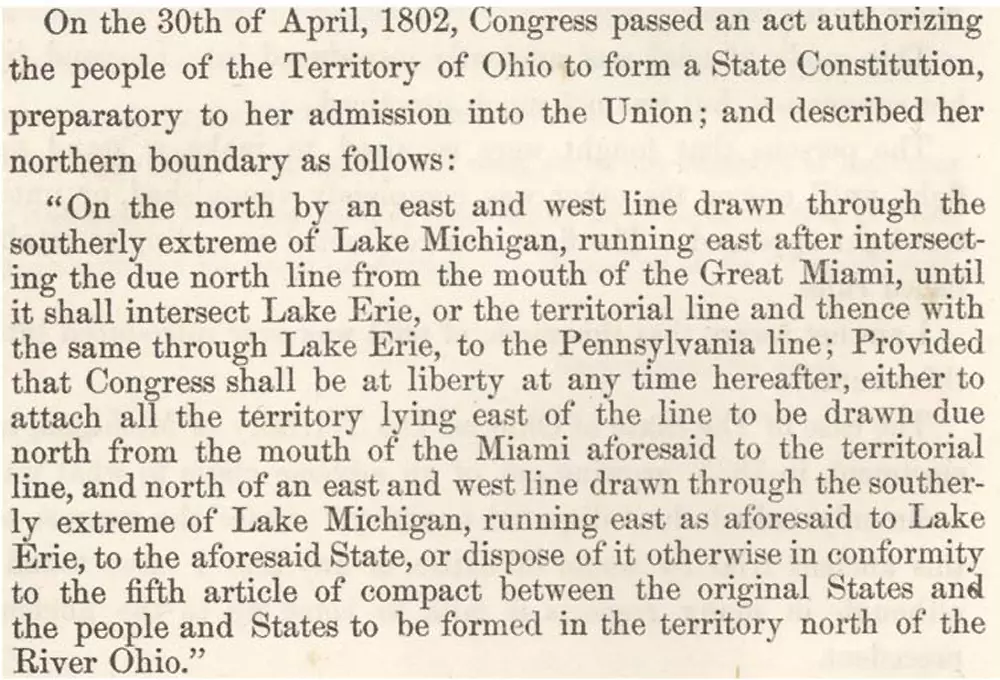

State constitution for he Territory of Ohio

State constitution for he Territory of Ohio

Later, in November of 1802, a constitution was drafted for the new state and included an additional section pertaining to its northern border. This addendum included the areas consisting of the future city of Toledo as well as most of Northwest Ohio. (For reference purposes, Miami River = Maumee River, Great Miami River = Ohio River in the SW corner of Ohio).

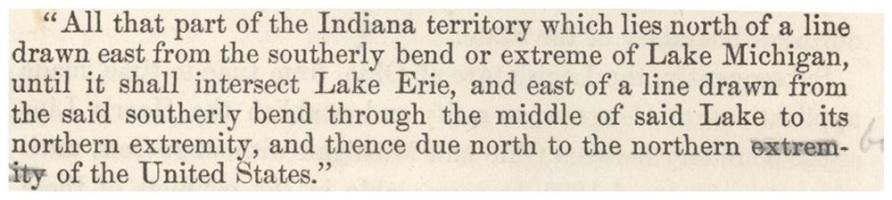

When Ohio was officially recognized as a state on February 19, 1803, the original border demarcations – not the border passed by the people of Ohio – were concluded to be the official borders of the state. Establishing Ohio state linesThe Territory of Michigan was officially formed on January 11, 1805. At the time of its creation, the borders of the territory were also determined. These borders created an overlapping area in what is now Northwest Ohio, which both Ohio and the Michigan Territory assumed they had legal jurisdiction over.

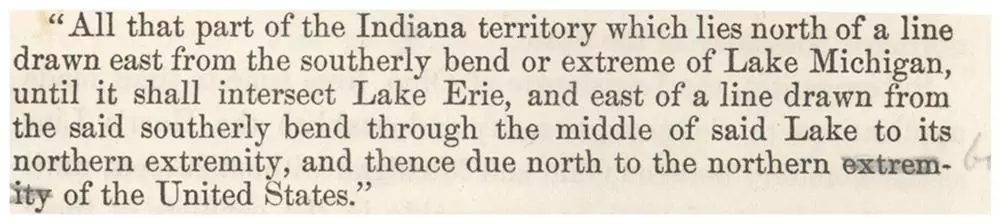

Establishing Ohio state linesThe Territory of Michigan was officially formed on January 11, 1805. At the time of its creation, the borders of the territory were also determined. These borders created an overlapping area in what is now Northwest Ohio, which both Ohio and the Michigan Territory assumed they had legal jurisdiction over.

Determining the True State Borders

Not surprisingly, the state of Ohio took umbrage with the new territory extending into land Ohio believed was its own.

After several years of lobbying, the Michigan Territory called for a survey in 1812 to determine the northern border of Ohio. Due to the renewed conflict with Great Britain in the War of 1812, however, it would take another five years for the survey to be completed. Upon its completion, surveyor William Harris found that the border was in line with the wishes of Ohio (ironically, the survey had been called for by Governor Cass of the Michigan Territory, with the borderline named after Harris). The survey was quickly ratified by the state legislature in January of 1818.

In 1819, the federal government intervened and called for its own survey, which was to be perfected by John Fulton at the bequest of President Monroe. This survey found the border to be in line with the original borders of the state of Ohio and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. With the acceptance of the Fulton Line by President Monroe, the Ohio border officially remained intact and unchanged until the showdown in 1835.

The Land in Question

It is possible that Congress failed to act in the determination of the border because the area in question was mostly inhabited by Ohioans or persons from the newly created territory of Michigan. The land contained valuable natural resources – such as the natural gas that would later power the Toledo glass industry – as well as valuable farmland, in addition to an important western port on Lake Erie. The land was also perfectly suited for an extension of the Miami and Erie Canals.

Conflict Begins to Boil

The first settlers of Toledo (which had been known by such names as Swan Creek, Port Lawrence, and Vistula) were originally subject to the laws of the Michigan Territory. As Toledo continued to grow, boosted by canal work sponsored by the state of Ohio throughout the area, the city began to notice that its continued growth was tied to being part of Ohio.

Michigan, under Governor Cass, began the statehood process in late 1833, which brought the border issue back to Congress. Congress quickly sent two surveyors to determine the actual border between Michigan and Ohio. Even though this survey concluded that the Fulton Line was correct, Congress still maintained the Harris Line as the official border.

Delegates of the young states of Illinois and Indiana supported Ohio in their border claim, mostly due to the fact that they, too, failed to follow the Fulton Line/border guidelines from the Northwest Ordinance and feared losing land to the new state of Michigan or the Wisconsin Territory. Even though Michigan was in line with all of the requirements for statehood, with the support of Illinois and Indiana, as well as that of Ohio and President Andrew Jackson, its first effort to gain statehood was denied. Former President John Quincy Adams, in discussing the blocking of Michigan's attempt to join the Union, stated: "Never in the course of my life have I known a controversy of which all the right was so clearly on one side and all the power so overwhelmingly on the other."

In 1834, with the support of a majority of Toledoans, a petition was forwarded to Ohio Governor Robert Lucas, urging that the boundary question be resolved and for the land to become part of Ohio.

The new Governor of the Michigan Territory, 22-year-old Stevens T. Mason, tried to formally negotiate a solution to the crisis in late 1834, but his request was denied by the Lucas government, who believed that this was an issue between Ohio and the United States, not Ohio and Michigan.

Lucas supported the idea of taking the Toledo Strip (as the area was now called) for Ohio and quickly passed legislation claiming the land belonging to the state. In 1835, county governments were created in the Toledo Strip; the portion of the Strip occupied by Toledo became known as Lucas County. Mason and Michigan acted quickly to this denial by passing the Pains and Penalty Act six days later. The new act called for all persons in the area in question to maintain loyalty to the Michigan Territory under the threat of "severe penalties," which included a $1,000 fine and up to five years in prison. To give teeth to this new legislation, Governor Mason appointed Brigadier General Joseph Brown to defend the area – but not start a conflict – against any Ohio actions that violated the new law. Governor Lucas also sent Ohio forces, now stationed just south of Toledo in Perrysburg. Governor Mason moved 1,000 Michigan soldiers further south into Toledo.

Battles of the Toledo War

Although one person was injured and there was one fatality (a horse belonging to Lewis E. Bailey of Michigan) during the conflict, there was only one recognized "battle." Even then, the Battle of Phillips Corner was not much of a battle by traditional standards.

Despite full knowledge of growing hostilities due to Mason's continued enforcement of the Pains and Penalties Act, in March of 1835, Governor Lucas instructed a group of men – led by Uri Seely of Geauga County, Jonathan Taylor of Licking County, and John Patterson of Adams County – to re-mark the northern border of the state according to the Harris Line. The project began on April 2, the day after Michigan elections in the Toledo area (Ohio would have theirs four days later).

On April 25, a small group of men from Adrian, Michigan encountered the "line-runners" from Ohio, intent on enforcing the Pains and Penalties Act. When the line-runners tried to flee arrest, warning shots were fired over their heads. All of the line-runners were arrested and taken to nearby Tecumseh, but the three men commissioned by Lucas escaped and reported back to him in Perrysburg.

The only casualty sustained during the "war" occurred in mid-July (the date is disputed), when Two Stickney, son of Major Benjamin Stickney and brother of One Stickney, stabbed Monroe County Deputy Sheriff Joseph Wood during an attempted arrest in the Toledo Strip. Governor Mason immediately ordered Two Stickney’s arrest. A large force tried to apprehend him, but he managed to escape again. In this attempt, however, the posse was able to arrest the elder Stickney and four other Ohioans. Mason demanded the extradition of Two Stickney to Michigan, but Lucas did not comply.

National Involvement and the End of the Toledo War

After discussing the Battle of Phillips Corner and contacting President Andrew Jackson by letter, Lucas dispatched Noah H. Swayne, William Allen, and David T. Disney to confer with the President in person. Jackson, with his Presidency already on shaky ground, wanted an end to this skirmish as soon as possible, preferably with no federal government involvement.

Even after the Battle of Phillips Corner and the Stickney incident, Lucas ordered the continuation of the re-marking of the border line, and again, Mason did not relent. This time, however, the federal government was firmly on Ohio's side. Mason was removed from office at the end of August, with Judge Charles Schuler of Pennsylvania installed in his place. When Schuler passed on the offer, John Horner of Virginia was given the position instead. In a show of support from the Michigan people, Mason was elected Governor (although Michigan had not been officially recognized as a state) and worked alongside Horner. After the crisis ended, Horner moved on to the Wisconsin Territory.

Michigan would continue to operate as though it were a state, electing Lucius Lyon and John Norvell Senators and Issac Crary Representative for the House. Although none of them would be permitted to vote in their respective chambers, they were allowed to stay as observers.

With the border line completed in November of 1835, Congress now took on the border dispute. In early 1836, Norvell and Crary informed Mason that the only way Michigan could gain statehood was to end the border conflict, turn over the Toledo Strip, and accept most of what is now the Upper Peninsula. On June 15, 1836, President Jackson signed into law the Northern Ohio Boundary Bill, which made the offer of the Upper Peninsula in exchange for the Toledo Strip official.

In late September, the delegation met in Ann Arbor to discuss ratification of the compromise. The first attempt at passing it failed. After four days of discussion, the legislature accepted the proposal in October. The second attempt to pass the compromise was convened on December 14, 1836, with the delegates voting to accept the proposal. The “Frostbitten Convention,” as it was called, had officially ended the Toledo War.

Michigan and Ohio Governors Woodbridge N. Ferris and Frank B. Willis declaring truce over state line markers, 1915

Michigan and Ohio Governors Woodbridge N. Ferris and Frank B. Willis declaring truce over state line markers, 1915

The area that is currently Northwest Ohio was officially given to the state of Ohio on December 27, 1836. On January 26, 1837, two years to the day that Governor Mason signed the Enabling Act, Jackson made good on his end of the compromise and admitted Michigan to the Union as the 26th state.

Importance of the Toledo War

What would the futures of Ohio, Michigan, and Wisconsin have been if Northwest Ohio had remained a part of Michigan? Would the city of Detroit have played such an important role in the state’s economy if Toledo were also in Michigan? Would the spike in Toledo’s population and wealth due to the glass and gas booms of the late 19th century have occurred if it were a Michigan city, thus not receiving funds from the state of Ohio for its canals?

What of west-central Ohio? Although this area would be populated eventually, without the canal projects that pushed travelers further south, the growth of these cities might not have occurred until the advancement of the railroad towards the end of the 19th century, or the automobile in the early part of the 20th.

And what would have become of northern Wisconsin if it had acquired the Upper Peninsula’s vast quantities of natural resources that went instead to Michigan, before Wisconsin had a national voice? It is possible that the northern portion of Michigan would not have grown as it has if the valuable resources of the area were under Wisconsin’s control.

Although the Toledo War was a skirmish over a relatively small tract of land, it would have drastically altered the future of these three states and possibly even more of the surrounding area had the outcome been different.

Bibliography

Galloway, Tod. "The Ohio-Michigan Boundary Line Dispute." Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. Volume 1. 1896. Pg. 199-231.

George, Sis. Mary Karl. The Rise and Fall of Toledo. Michigan. Michigan Historical Society. Lansing, MI. 1971.

Jones, Tom. "The War Between Michigan and Ohio." The Detroit News. May 21, 2000.

Mendenhall, T. C. and A. A. Graham. "Boundary Line Between Ohio and Indiana, and Between Ohio and Michigan." Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. Volume 4. 1896. Pg. 127-199.

Way, W.V. The Facts and Historical Events of the Toledo War of 1835: As Connected with the First Session of the Court of Common Pleas of Lucas County. Daily Commercial Steam Book and Job Printing House. Toledo, OH. 1869.

Winter, Nevin O. A History of Northwest Ohio: A Narrative Account of Its Historical Progress and Development from the First European Exploration of the Maumee and Sandusky Valleys and the Adjacent Shores of Lake Erie, Down to Present Time. The Lewis Publishing Group. Chicago. 1917.