The entrance to Woodlawn Cemetery

The entrance to Woodlawn Cemetery

Exhibit Gallery

Photo credits: Josef Schneider (all Woodlawn photogragraphs) and Larry Leach (Doria and Thomas T Tracy).

Historic Woodlawn Cemetery was recognized as a National Historic site in 1998. The overall landscape design, which follows the principles of the rural cemetery movement, is a significant feature of the district and has been counted as a site. Woodlawn Cemetery has maintained its integrity as a fine example of the "rural cemetery" plan. The rural cemetery incorporates the natural beauty of the landscape with carefully planned lots, and this is what the founders of Woodlawn Cemetery had in mind when they chose the present site. The cemetery association has been careful to maintain the natural landscape and high quality grave markers. Kirk Holdcroft, current Director of the cemetery (1993) and President of the Board of Trustees (1994), is committed to ensuring the cemetery continues in this tradition.

*What is a necrology? In short, it means "obituary" (Meriam- Webster), a "list of deaths" (Oxford), or a notice of deaths including a biography (vocabulary.com). In older practices (e.g., in monsteries, cemeteries), necrologies were "registers containing the entries of deaths of persons connected with, or commemorated by" an institution or organization (based on a definition in The Compact Edition of the Oxford English Dictionary, 1970)

About the University of Toledo's Historic Woodlawn Cemetery Project (1995)

During the 1995 winter term, members of Dr. Diane Britton's public history practicum class at the University of Toledo researched and wrote a history of Woodlawn Cemetery. Students worked with sources at the cemetery's administrative offices, the local history collection of the Toledo Lucas County Public Library, the Toledo Blade, the University of Toledo's Canaday Center Archives, and the Lucas County Auditor's Office. They also conducted field surveys and spoke with people in the community familiar with the cemetery's past. The study of Woodlawn provides an example of the way that public history at the University of Toledo focuses on community outreach activities and cooperative projects. The program emphasizes the application of historical knowledge and methodology beyond academe that encourages a consideration of the past in daily life. As a cultural and historical institution, Woodlawn Cemetery tells us much about Toledo's past and provides an important resource for studying local history.

Woodlawn Necrology Index

Toledo's Woodlawn Cemetery

From "Notes from the Editors" by Charles N. Glaab. Northwest Ohio Quarterly, Winter 1996

The subject of this issue-the history of cemeteries in Northwest Ohio-presents an opportunity for more tranquil observations than our editorial comments of late on the current "war against history." But perhaps not entirely. Much of the rancorous debate on the effort to establish national standards for the teaching of history or for exhibits on the Enola Gay, Sigmund Freud and slave life assumes the existence of an irrefutable body of historical knowledge that can be uncovered by trained historical scholars to produce a true conclusion-perhaps not a scientific truth but something nearly so. But this is not the history we seek when we visit a cemetery. The single-minded analysis that is a part of contemporary debate overemphasizes the unity of historical knowledge. In his famous critical essay, "The Use and Abuse of History," Frederick Nietzsche pointed out that history exists at different levels of comprehension, all of which have a measure of validity -or in his view, more exactly, a lack of validity. Among these are the "antiquarian," which connects an individual with a place and creates the impulse to survey "the marvelous individual life of the past" and identify oneself "with the spirit of the house, the family, and the city." For the individual the "history of the town becomes the history of himself." 1

It is ordinarily this antiquarian imperative that impels people to visit country graveyards, the remaining burial grounds in our cities and the modern cemeteries of recent times-to observe the tombs of the famous, and to wonder at the creativity of monuments to death. The antiquarian impulse strengthens, of course, with age. The young fear the graveyard, as they experience the first shudder of mortality. The japery imposed on every child who grew up in a small town-"I went out to the cemetery today; I saw everyone I know there"-acquires new dimensions as years pass. But a visit to a graveyard seldom evokes a sense of one kind of historical reality, that the mountebank and the reprobate, the cruel and the avaricious-the villains who fill our academic histories-lie there. More often, as Nietzsche observes, one simply "looks back to the origins of his existence with love and trust; through it he gives thanks for life." 2

Nietzsche’s antiquarian impulse, which takes many to the historical museum or historical site, or the graveyard, may be as much a mystical as a historical experience. When we visit these places seeking historical dimensions, we seldom are searching for the historical truths of the academy. Nevertheless, a tour of the cemeteries of the Toledo region, some of which are portrayed in a photographic essay in this issue, provides a few obvious insights into historical forces that shaped American society. Notably demonstrated is the unity of Western civilization; there is little cultural diversity in the iconography of Christianity. Christ figures, cherubim and angelic hordes abound alongside the symbols of the civilization of Greece and Rome. The omnipresent obelisks and occasional pyramids represent part of a nineteenth-century cultural effort to tie Europe and America to ancient Egypt, the first civilization, it was thought, upon which had been built the civilization of Europe. The 20th-century temperament replaces ornate Victorian statuary with cubes and spheres and the occasional minimalist mausoleum, while a continual fascination with technology makes trains and airplanes the celestial omnibus. (The World Wide Cemetery on the Internet and laser sealing of durable pictorial images on tombstones represent the latest homage to technology in memorializing the dead. 3) In the latter years of the century, the traditional cemetery of monuments and statuary has often been succeeded by the ultimate in minimalism-the memorial park with acres of grass and occasional shrubbery, but with no raised tombs to disturb the sublimity of nature.

The cemeteries of the Toledo region are for the most part a product of the modern period of cemetery building-the era of the "rural cemetery" movement, which began in Europe and America in the early years of the nineteenth century. Before then the dead were interred in church burial grounds, producing such familiar reflections on death as those in Gray's "Elegy." One of the more moving passages in early American letters is to be found in the famous diary of Samuel Sewell, the Puritan magistrate instrumental in the hangings of Salem witches. The day after the sudden death of his two-year-old daughter Sarah on December 23, 1696, he laments his part in the Salem trials. On Christmas day, his entry records the events of the burial, the reading of Biblical passages by his three young surviving children and friends bearing "my little daughter to the Tomb." After a visit earlier in the day to the brick-lined excavation located in Boston's New (afterward the Granary) Burying Ground, he wrote: "Twas wholly dry, and I went to see in what order things were set; and there I was entertain'd with a view of, and converse with, the Coffins of my dear Old Father Hull, Mother Hull, Cousin Quinsey, and my Six Children: for the little posthumous was now took up and set in upon that that stands on John's: so are three, one upon another twice, on the bench at the end. My Mother ly's on a lower bench, at the end, with head to her Husband's head: and I order'd little Sarah to be set on her Grandmother's feet. 'Twas an awfull yet pleasing Treat: Having said, The Lord knows who shall be brought hether next, I came away." 4

In late-eighteenth-century Europe a new concern with the dead started a movement for large burial grounds in natural settings away from populous areas of cities. The use of the term "cemetery" (cimetière in French) instead of the more common Old English-derived word "graveyard" reflected in part an effort to relate death to the natural universe posited by Romanticism. The word cemetery came from the Greek word for sleeping chamber, a place of repose. The new model for the rural cemetery, Père la Chaise in Paris, opened in 1804 with hundreds of acres on the city's eastern outskirts. Its founding was the result of the 1765 Parliament of Paris decree that closed all cemeteries in the city and required the movement of corpses outside its limits. By the end of the first decade four rural cemeteries had been established around Paris, with Père la Chaise's plan for a vast, rustic, garden-like burial ground followed shortly in London, Genoa and Vienna. The new cemeteries became popular gathering places for lovers and families on Sunday promenades. 5

Within American cities, in particular New York, Philadelphia and Boston, early- nineteenth-century church burial grounds had become overcrowded and badly maintained, while the great demand for urban land forced the reburial of many. In addition, before midcentury when the germ theory of disease first began to gain credence, prevailing medical thought emphasized the dangers of disease-causing miasmas from contamination.

Public health authorities warned about exhalations arising from graveyards, while physicians argued that decaying corpses contributed to the devastating yellow fever epidemic of 1822. These influences, along with Romanticism's conception of nature's positive effect on mind and body, contributed to the movement for rural cemeteries in the United States.

The first American cemetery tied to this movement was Mount Auburn, established in 1831 on a seventy-two-acre site on the Charles River, four miles from Boston, an area described at its dedication as having "vigorous growth of forest trees" on land "beautifully undulating in its surface, containing a number of bold eminences, steep declivities, and shadowy valleys." 6 The quick success of Mount Auburn influenced leaders in other U.S. cities to establish rural burial grounds; it, Laurel Hill in Philadelphia (1835) and Greenwood in Brooklyn (1838) were the three cemeteries that influenced the national movement. In 1849, when Toledo was just beginning to grow as a city, Andrew Jackson Downing, popular advocate of nature in the early years of the century, declared, "There is scarcely a city of note in the whole country that has not its rural cemetery." 7 The establishment of this movement was related to the emergence of the urban park movement in the mid-nineteenth century. Early advocates of parks, such as popular nature poet and New York editor William Cullen Bryant, noted that urban dwellers were finding their way to the new cemeteries in large numbers. Nature's benefits to body and soul, he argued, should be brought to the city itself.

The two cemeteries represented in articles in this issue- Woodlawn in Toledo and Oak Grove in Bowling Green-represent well the characteristics of American rural cemeteries, as do many others in the region, in particular Wolfinger Cemetery in Secor Metropark and Swan Creek Cemetery, west of the city of Maumee on Highway A20 in Monclova Township. The former is enveloped by the metropolitan area's most naturalistic park setting, while the latter, although properly a church graveyard, seems to extend almost organically into a heavily wooded ravine with creek. Forest Cemetery, the oldest in the city of Toledo, contains the most elaborate statuary in the region and provides the most striking vistas of the natural park cemetery surrounded by a modern city. The iconography of Roman Catholicism in America is probably best represented in Calvary Cemetery. That cemetery is related to the effort to bring nature to the city through the establishment of parks (in this case nearby Ottawa Park) connected throughout the metropolis by tree-lined boulevards (in this case, Parkside Boulevard). There are also significant reflections of the past in smaller sites such as Haughton Cemetery, which is completely surrounded by the continuous strip mall of the business section of West Toledo. Most motorists would scarcely notice it, although children from a neighboring school continue to visit it yearly as part of the formal observances of our sole important pagan holiday, Halloween. The modern cemetery can still provide the kind of haven it did in the early years of the nineteenth century. The popularity of bicycle touring in the latter part of this century, for example, has led to a rediscovery of the cemetery as the "charming pleasure-ground" of which Downing spoke. A splendid guide to the back roads of Ohio for bicycle touring, published in various editions by Jeff and Nadean Disbato Traylor under the series title of "Life in the Slow Lane," identifies many of the state's most attractive cemeteries. 8 One of this writer's favorites from the guide is the 1808 Hopewell Church Cemetery, located south of West Florence and Highway 22 on Fairhaven Road, with its unusually attractive stone wall fronting the site. Not listed in their work is the Auglaize Church of God Cemetery near Fort Brown and the town of Grover Hill, which provides a tranquil bird watching spot and in the summer the near certainty of seeing groups of deer in the field and woods that encapsulate the small grave site that runs alongside a flowing creek. Harrington Cemetery in the heart of the town of Elmore, surrounded by wrought iron fencing, contains splendid grave markers from the early nineteenth century. St. Elizabeth Cemetery, to the west of Toledo, and Oak Hill on the southern edge of the metropolitan area are two of the scores of cemeteries that provide tiny natural havens from the mile upon mile of flat cultivated farmland that make up the region.

Perhaps this special issue of the Quarterly will not only stimulate interest in the historical significance of American cemeteries but also create some awareness of the neglected fact that cemeteries in this region and elsewhere preserve in part a natural world that we seem to be losing in modern metropolitan America.

NOTES:

1 Quoted in Michael Kammen, Selvages & Biases: The Fabric of History in American Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1987), 162.

2 Quoted in ibid., l62.

3 The Detroit News and Free Press, 27 May 1996.

4 M. Halsey Thomas, The Diary of Samuel Sewell, 1674-1729, 2 vols. (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, l973), 1:364.

5 For a concise discussion of the origins of the rural cemetery movement in Europe and America, see David Schuyler, The New Urban Landscape: The Redefinition of City Form in Nineteenth-Century America (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986), 37-56.

6 Quoted in ibid., 43.

7 Quoted in ibid., 47.

8 Life in the Slow Lane: Fifty Backroad Tours of Ohio, rev. ed. (Columbus: Backroad Chronicles, 1992).

Text of National Parks Service Historical Site Nomination for Woodlawn Cemetery (NPS Form 10 900 OMB No. 1024 0018) by Linda Jeffrey.

WOODLAWN CEMETERY, LUCAS CO. OH.

Narrative Description (Section 7: pp1-6)

Historic Woodlawn Cemetery is nominated to the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. The overall landscape design, which follows the principles of the rural cemetery movement, is a significant feature of the district and has been counted as a site. Woodlawn Cemetery has maintained its integrity as a fine example of the "rural cemetery" plan. The rural cemetery incorporates the natural beauty of the landscape with carefully planned lots, and this is what the founders of Woodlawn Cemetery had in mind when they chose the present site for the cemetery. The cemetery association has been careful to maintain the natural landscape and high quality grave markers. Kirk Holdcroft, currently the Director of the cemetery (1993-) and President of the Board of Trustees (1994-), is committed to ensuring the cemetery continues in this tradition.

The cemetery was originally situated outside Toledo’s city boundary, but by 1900 the rapidly growing city had enveloped the site. The area surrounding the cemetery reflects the sprawling nature of the city of Toledo. The area is a mixture of residential housing, city park, and semi-industrial zones. The housing situated across West Central Avenue on the southern boundary is an outer lying part of the Old West End historic district (NR, 1973; 1984), while across Jackman and Hillcrest Roads is modest residential housing. Willys Park marks the cemetery’s eastern border. Across from Willys Park is the nationally renowned Jeep plant. Today the cemetery’s natural landscape remains unblemished amidst the urban sprawl as a monument to the people and the spirit that built Toledo. The cemetery is not only a park, but also an arboretum, a bird sanctuary, museum, historical archive, and an important cultural and social landmark for Toledo.

The cemetery was laid out according to the landscape lawn plan which was promoted by Adolph Strauch, Superintendent of Spring Grove Cemetery (est. 1845) in Cincinnati (NR, 1976). Strauch also designed Greenwood Cemetery in Hamilton, Ohio (NR, 1994) This was a modification of the original rural cemetery movement as a response to problems that became apparent in early rural cemeteries. The landscape lawn plan, with monument only, was an effort to restrict patrons who decorated their individual lots with disregard to the general effect on the landscape. This threatened to detract from the landscape effect, which was a principle feature of the rural cemetery movement. Woodlawn’s parklike appearance and careful attention to ensuring grave markers, tree plantings, and roadways best compliment the landscape is an example of the movement to form a consistent whole. Strauch’s idea was that the best effect is obtained "when broad undulations of green turf prevail, adorned here and there with a noble family monument, and at proper intervals shaded with suitable trees. Such lots, blending the elegance of a park with the pensive beauty of a burial place, confer on the whole a grace and dignity which can never be obtained in situations where every foot of ground is occupied with ornamental puerilities[sic]" (Description of Woodlawn Cemetery, 1883).

Woodlawn made a conscious effort to obtain the best talent during initial planning in order to develop "one of the finest cities of the dead in the West" (Description of Woodlawn Cemetery, 1883: 9). Schwagerl and Co. of Philadelphia drew up the original lawn plan map for Woodlawn’s lots and sections. The cemetery continues to follow this design to this day. The natural landscape is one of gently undulating terrain. A stream that flowed into cemetery grounds fed a ravine that cut through the site. By damming the lower end of the ravine with soil and stone masonry an artificial lake was allowed to form. The cemetery has two connecting ornamental lakes that feature three small islands. The lakes are central features of the site (see Map 3).

Woodlawn’s natural terrain was complemented with plantings and roadways that were subject to a general plan. Trees were planted in groupings according to variety, and interspersed with shrubbery, to obtain the best effect. Winding roadways, instead of rectangular roads, provide access to the sections and complement the landscape effect (see map 2 and 3). Although the roads have been resealed they are basically the same width as they were historically and maintain the integrity of the rural cemetery movement. The sections and lots are of various shapes, sizes, and positions to cater for different tastes and requirements. Those that are in prominent positions (by roadways or overlooking the lakes) were the more expensive sites.

The site features six buildings, four contributing and two non-contributing. The four that have been categorized as contributing resources are the office, crematory chapel, comfort station, and cemetery residence. The non-contributing buildings are the new crematory and service building. The cemetery is encircled by an iron fence, and includes two connecting lakes. A bridge spans the larger lake, while a land bridge is situated where the larger lake runs into the smaller lake. Other objects on the property include exquisite private mausoleums and monuments. The forty-two mausoleums or monumental tombs, and the bridge and fence are classified as contributing structures, while the G.A.R. Civil War monument, Ludwig, and Gunckel monuments have been classified as contributing objects.

The Stewert Iron Works Company of Cincinnati, Ohio erected the two-mile iron fence that surrounds the cemetery in 1915. The entrance, which faces the intersection of Auburn and Central Avenues, features six stone pillars, three on either side of the gate. Each pillar is decorated with ornate ironwork. The large iron gates hang on the pillars, one on either side of the driveway (photo #4).

The unique office building, which was built in 1903, is situated at the entrance gates (photo #5). This irregular and unusual building is dominated by a bell tower which is believed to be the centerpiece remains of an old windmill that was located on the site in the late nineteenth century. The office building seems to be "wrapped around" the tower. The tradition of tolling the bell to signal the arrival of a funeral procession continues today.

The building is Romanesque in style. Its walls are of rock-faced coursed Ohio limestone and a roof of slate tops it. The belfry is similar to a battlement and has a large square window on its front and rear, while on each side of the belfry there is an arched window. None of the windows have panes or shutters.

The office building has retained its historical integrity, and appears on the exterior much as it did when it was built. The interior was completely renovated in 1985 to create more room. This included the modification of the entrance door to the building as well as one of the windows to allow for more light. This is the most distinctive building in the cemetery (photos # 5, 6, and 7).

Asphalt lanes gently wind their way through the valleys and rolling landscape of Woodlawn Cemetery. A concrete bridge, built in 1913 by engineers Wyncoop and McGormley, traverses the lakes. It was rehabilitated in 1965 at a cost of nearly $35,000 (photo #8).

The chapel is situated on the northwest side of the bridge and overlooks the lake. It was dedicated in 1883 and is the earliest remaining building on the property. The chapel was built on top of a receiving vault, which was used to house those who died in the winter months. At this time of the year the ground was frozen, and at the turn of the century technology had not been developed to dig the frozen soil. Bodies were placed in the vault to wait for the spring thaw. The vault, featuring a domed ceiling, was turned into a crematory chapel in 1923. Woodlawn was the first and only cemetery offering cremation as a service in northwestern Ohio, and as late as 1952 Detroit was the closest city with cremation services. The original crematory retort is still found in the basement of the chapel (photo #9) (Glimpses of Woodlawn:9-13, Manuscript Collection).

The exterior of the chapel has undergone extensive remodeling due to the deterioration of the woodwork and effects of fire and smoke. The crematorium created the need for a chimney that was erected on the right side of the chapel. It is assumed that around this time the cupolas that existed on the four corners of the roof were removed. The central cupola still exists. The frieze was also removed. The ornate canopy covering the entrance to the chapel was removed and replaced with a simple suspended overhanging cover (date unknown). A transom is featured over the canopy. Unfortunately the original stained glass windows were destroyed in the 1973 chapel fire and were replaced with green and yellow glass. After a second fire in 1991-2 the existing purple (blue) and clear plexiglass was installed. The frames have retained their original "round arch" shape, although the windows are now less intricate (photos #10, 11 and 13).

In a 1952 remodeling, the chapel stucco was removed and replaced with brick veneer. Eight years later the old asbestos and shingles were removed from the chapel roof. All the rotten sheathing was also removed at that time and replaced with new shingles and gutters. The brickwork on the corner buttresses has been covered with brick veneer and the walls have been plastered with stucco (probably to combat the smoke stains caused by the crematory emissions). The chapel has maintained its basic structural integrity despite undergoing superficial alterations.

The interior has remained intact and retains its integrity. The chapel is symmetrical and is particularly notable for its vaulted ceiling (photo #12). The double door has a fanlight overhead and each of the three arched multipaned windows is framed by a pillared arch (photo #13).

The chapel interior instills a sense of softness and serenity. The design is simple and in the secular tradition of the rural cemetery movement. The chapel is no longer used for services or cremations. A modern service building was constructed between the residential house and office in 1986. The new crematory, which began services in 1995, is located between the office building and service building (photo #14). These two modern buildings are considered non-contributing.

Next to the chapel is the comfort station that was erected in 1923 (the same year the crematorium was installed). The comfort station is constructed of Ohio limestone and is also simple in style. It consists of one rectangular room and has a hip roof with an end interior chimney. The building is split-level, and the front of the building has a single centered door with two multipaned windows on either side. The rear of the building is two stories, with four windows. A door to the basement is located at the side of the building. Today the comfort station is largely unused. During the winter the cemetery peacocks are housed on the lower floor (photos #15, #16, and #42).

Located on the Central Avenue side of the cemetery, 500 feet west of the office building, is the cemetery caretaker’s residence (c. 1917). The residence is commonly thought to be a Sears house, unfortunately there is no documentation to confirm this belief. It is still occupied today (photos #17 and 18).

At Woodlawn Cemetery there are forty-two private mausoleums dating from the 1880s. The last was built in the 1950s. Some of the notable mausoleums belong to the Chesbrough (one of the first built in the late 1880s), Stranahan (1935), Spitzer (c.1900), Berdan (c.1900), and Snyder (c.1930) families. The mausoleums provide eloquent examples of funereal architecture (photos #19, 20, 21, 22, and 23).

The Spitzer and Snyder mausoleums, which face each other on the main driveway near the entrance to the grounds, complement each other. The grand and imposing Spitzer mausoleum is neoclassical. Three levels of granite steps lead up to the six columns and two doors at the entrance of the mausoleum (photo #24). The Snyder mausoleum is delicate and modest in scale, yet artistically perfect. Its four columns and rounded sculpture design in a park setting provide a good contrast to the Spitzer mausoleum (photo #25). The Browning mausoleum is a good example of Egyptian Revival architecture. This style was popular during the mid-nineteenth century, and especially popular during the 1920s with the discovery of King Tutankhamen’s tomb. (Gordon: 82) The Browning mausoleum features reeded columns with horizontal banding. Roman numerals on the steps read 1910. (Photo #26)

In addition to the excellent examples of mausoleum architecture are numerous monuments. Woodlawn Cemetery has prided itself on encouraging the originality of monuments and mausoleums. The Lloyd Brothers (Walker) Monument Company continues to emphasize individuality of design and style for every sculpture they work on, as reflected in the unique and distinctive monuments found in the cemetery. Some of the mausoleums on the property also contain impressive examples of Tiffany glass dating from early in this century (photos #33 and 34). The Stranahan and Tiedtke (c. 1920) mausoleums have examples of fine bronze relief work on their doors (photos #35 and 36).

The Ford monument is also an interesting example of neoclassical architecture. A colonnade of imposing granite frames the large urn that sits on a pedestal. Stairs lead to the urn (photo #37). The James B. Bell monument, also neoclassical, consists of a benchseat that is canopied by an arch. The arch has the relief of a tree on the square pillars either side of the bench. The arch has two pillars at each end, which support an entablature of simple design that reads "Until The Day Break And The Shadows Flee Away."(Photo #38)

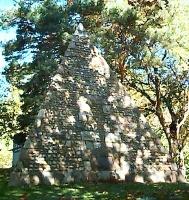

Some of the well-known and more unusual monuments include the pyramid erected for John E. Gunckel in 1917 (Photo #39), the Bessie Ludwig chair monument, 1930 (Photo #40), and the G.A.R. Civil War monument, 1901. Two graves that are included in the section are those of Civil War veterans Henry G. Neubert (Photo #41) and Major General James B. Steedman. Both monuments feature a bronzed bust.

Woodlawn also displays examples of the late Victorian "fad" which incorporated monuments that resembled trees instead of common styles. The trees are truncated and have had all the branches cut off; this is to represent an unfinished life (photo #27). An organization called the "Woodsmen of the World" offered a $500 subsidy if its logo was allowed to appear on such monuments.

The site is important regionally due to the exceptional architecture and artistic design of buildings and structures that are found within its boundaries. The property consists of a carefully planned and developed landscape, which emphasizes nature and a park like setting. The Cemetery Association has been careful not to mar the historical and architectural integrity of the cemetery. The four notable buildings, fence, and bridge that are located on the property date from 1883 until 1923. Woodlawn cemetery is maintained in the spirit in which it was founded and is a good representation of a rural cemetery. Everything in it is, as Adolph Strauch said of rural cemeteries, "tasteful, classical, and poetical" (Linden-Ward: 31).

Narrative Statement of Significance (Section 8: pp7-13)

Woodlawn Cemetery is eligible for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places under criterion C and criteria consideration D in the areas of landscape architecture and architecture. Woodlawn cemetery is a "historical document" which provides insight to changing American burial practices in the nineteenth century and reflects the physical and cultural development of Toledo. Woodlawn Cemetery maintains the integrity of the principles on which it was founded and the original designed landscape remains the organizing feature of the cemetery (see maps provided).

Woodlawn Cemetery is significant for cemetery and landscape planning in Toledo as it represents both the reform of Toledo’s burial customs and a concerted effort to provide city dwellers with a sylvan place to escape urban life and return to the pastoral ideals of nature. The founding of Woodlawn Cemetery in 1876 introduced the landscape lawn plan, a modification of the rural cemetery movement, to Toledo. (David Sloane in The Last Great Necessity (1991) recognizes Toledo’s importance as part of this movement: 121). The rural cemetery movement became popular in the nineteenth century as city leaders realized burial grounds had to be reformed. Graveyards within cities had become offensive and posed serious health hazards. They were depressing, neglected, crowded, and revolting. Graveyards had degenerated into little more than "stinking quagmires." Nor did they provide the dead with a permanent resting place because as the city grew, and close relatives moved away, the properties were often seized by land hungry developers who would uproot the dead (French: 42).

During the early nineteenth century attitudes towards death and commemoration were undergoing a dramatic change. The harsh views of the Puritans, which emphasized fear and finality, gave way to a gentler spirit of sentimentality and melancholy. It was also believed that rural cemeteries would provide cultural and moral uplift for city dwellers in an increasingly urban world, as well as inciting a sense of historical continuity and a feeling of social roots. Rural cemeteries were therefore important social and cultural institutions. (French: 59)

A large emphasis was placed on nature and art. The rural cemetery included lakes, gently undulating land, trees, originality of monuments, and carefully planned lots. The term "rural" was used as the cemeteries were originally built outside the city on large pastoral tracts. Today the cities have grown up around them and they have become "pastoral oases in the midst of urban sprawl."(Clendaniel: 6) Woodlawn Cemetery was the first effort to provide Toledo with a large and magnificent park.

The "rural cemetery" movement began in America in 1831 with the establishment of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Boston. Forty-five years later Toledo followed the national trend and founded Woodlawn Cemetery three miles from downtown. (There are four "rural cemeteries"in Ohio that are included on the National Register. These are Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati (1845); Woodland Cemetery, Cleveland (1853); Union Cemetery, Steubenville (1854); and Woodland Cemetery in Dayton (1841) which is listed on the National Register for its gateway, chapel and office and is one of the nation’s five oldest rural cemeteries.

The first permanent provision for burial of the dead in Toledo was Forest Cemetery, which was established in 1839 on eight acres of land outside the city. By 1865 the land was filled and the city decided to expand the cemetery by buying some of the land adjacent to it. It was apparent that a new cemetery would have to be established in the near future.

In 1865 a committee composed of local businessmen met to discuss solutions for the burial problem and eventually selected a site in Washington township three miles from the city. The selection was rejected by the city council, however, because it was too distant from the city. Even though the land was not chosen then, the committee was able to see the possibilities it presented. Ten years later this site would be selected as the site for Woodlawn Cemetery by a group of citizens who met at the Boody House in 1876. The location was favored because it had undeveloped land around it that would allow the cemetery to be easily enlarged when required. (Woodlawn Cemetery 1882:2)

It is interesting to note that Frank J. Scott was present at this first meeting. At the same time Scott, an architect, was involved in the development of the Old West End which is recognized as one of the largest collections of late Victorian and Edwardian mansions left in America (Historic Places marker located in Old West End). Located near the cemetery many who lived there now reside at Woodlawn, their monuments and mausoleums as grand as their homes.

The Woodlawn Cemetery Association was organized in 1876. The charter members were: William St. John, D. W. Curtiss, Henry S. Stebbins, Edward Malone, Herman D. Walbridge, Terome L. Stratton, C. P Griffin, Henry Phillips, George Milburn, J. Kent Hamilton, Horace S. Walbridge, Charles E. Phillips, George B. Brown, Albert E. Macomber, Charles H. Eddy, E. B. Hall, and Benjamin F. Griffin. At a later meeting the first officers were elected. Horace S. Walbridge and Charles B. Phillips were elected President and Vice President respectively, and Herman D. Walbridge was made the treasurer.

Woodlawn Cemetery was developed according to the landscape lawn plan which was promoted by Adolph Strauch, Superintendent of Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati. Strauch identified problems that had been exposed through the experiences of earlier rural cemeteries. He had visited Spring Grove and was critical of the cluttered lots. Objects that were added to individual lots in different cemeteries included "[N]umerous tin cans, old broken vases, broken pitchers, cracked glasses, lidless coffee pots, lard buckets," iron gates, fences, and benches. This was a custom that most cemeteries would have trouble combating.(Linden-Ward:29-30, Manuscripts, Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Convention 1897:22-23)

In 1854 Spring Grove hired the young Prussian as landscape gardener and appointed him superintendent in 1859. Strauch reformed the "rural cemetery" movement by emphasizing simplicity. He encouraged less ornamentation of individual lots, restrictions on lot enclosures, and less development of the natural form of the land. The aim was to provide a park for the city. Woodlawn was part of the modified "rural cemetery" movement and was the first effort in Toledo to provide the city with a large and magnificent park.

The first superintendent at Woodlawn, Frank Eurich (1876-1900), is credited with much of the original landscaping and early tree planting on the site. Woodlawn is not only a place for the dead but has also become an arboretum of national recognition. Eurich had been a member of the staff at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia and helped in the construction of the Memorial hall. He was an authority on horticultural matters and had a distinguished career in cemetery management. Letters were sent to him from across the nation requesting information on plants and trees and he kept up a lively correspondence with cemeteries, both regionally and nationally, concerning cemetery matters. He often received letters complimenting him on Woodlawn Cemetery and the chapel. (Emch: 48, Correspondence 1880s-1900).

Eurich was cofounder of the Association of American Cemetery Superintendents that was formed in Cincinnati in 1887. The association met to discuss problems, and recent trends and developments in the cemetery business. He assisted in the creation of some twenty-five cemeteries based on the "lawn plan" that was pioneered by Strauch. Much of the landscape and plant life at Woodlawn is the result of the hard work and vision of Frank Eurich. He desired a mixture of both national and international influences, both rare and common, to create a cemetery that adhered to the ideals of the rural cemetery movement. (Emch: 48) The 300 different species of trees at the cemetery include Tupelo, Iron Wood, American Elm, Purple Beech, Chanticleer pear, Siberian Pea, and Pecan. There are two state champion trees at Woodlawn Cemetery. One is a 75 ft White Fur while the other is a Purple European Beech, both were planted during the early years of the cemetery between 1876 and 1900. ("The Trees of Woodlawn Cemetery" by Glenn Firebaugh, printed in the 1976 Naturalist Yearbook, includes extensive identification of the trees at Woodlawn and provides their locations). The cemetery is also a bird sanctuary featuring 200 different species. It is an attraction for botanists, birdwatchers, and school children alike.

Edward O. Schwagerl, from Philadelphia, was also prominent in the early landscaping of Woodlawn Cemetery. Schwagerl, consulting landscape architect and engineer, provided early sketches of the landscape and worked with Eurich on designs for the chapel. Schwagerl had designed the Riverside Cemetery in Cleveland on the "lawnplan." (Emch: 45-46)

The "conservatory chapel" at Woodlawn was dedicated in 1883. Although much grander in conception the conservatory that was to be added later never was due to recurring financial problems and World War I. These factors saved the chapel in the 1930s. The association considered demolishing the original chapel and constructing a new chapel and public mausoleum but the outbreak of the Great Depression and World War II put the plans permanently on hold.

Woodlawn Cemetery has been actively involved in events associated with the growth of the community. The history of the site is a monument to the immense growth the city of Toledo has experienced in 120 years. The location was originally part of Washington township and was initially rejected because it was deemed to far away to serve the city. In 1887 the Cemetery Association wanted to make the grounds more accessible to the city and discussed the possibility of a streetcar railroad. In 1892 the cemetery Board gave permission to the Metropolitan Street Car Railway Company to "construct, maintain and operate" a single track railway on and along Central Avenue, from the westerly city line to the cemetery gates opposite Auburn Avenue. The railroad was built providing access to the cemetery for Toledoans who lived in the city. (Minutes)

The city spread quickly, and by 1908 the city limits had reached the Central Avenue boundary of the cemetery. The increased use of the park-like settings that was permitted by the street cars, close proximity of the city, and the advent of the auto caused problems for cemetery management. The rural cemetery proved so popular that the majority of visitors were not visitors but sightseers and people seeking recreational space. The role of the cemetery had changed to one of a park and outdoor museum. The crowds and holiday mood became so great that cemetery management had to pass rules and regulations that restricted the excesses of some of the patrons. The association was uncomfortable with the increased public use of the cemetery as a place of leisure and passed rules and regulations to protect the ambiance and serenity of the grounds. The Board of Trustees cited problems with straying horses, shooting guns, loud music, and an influx of spectators to funerals. It was mentioned that as soon as an open grave was visible scores of people flocked to the cemetery grounds to watch the burial, especially on Sundays. Officials were disgusted that such a somber occasion provided entertainment for the masses. Rules were passed prohibiting children from using the lakes for skating, fishing and swimming. Other cemeteries also expressed dismay at the thought that they had become little more than theme parks. (Minutes, Rules and Regulations handbook, Zanger: 24-26).

The cemetery was responsible for providing the traffic lights at the entrance gates in 1935. The intersection at Auburn and Central Avenues was considered so dangerous that the cemetery paid for and owned the lights until the city took them over a few years later. In 1946 the cemetery was again actively involved in the affairs of the city when it loaned a parcel of unused land on the Hillcrest side of the property to the city for veterans housing at the end of World War II.

The office building was constructed in 1903 and it provided an impressive sight for the visitor at the entrance gates. About 1917 the caretaker’s house was built. In 1923 the comfort station and crematory were added to the cemetery. The date chosen to end the period of significance is 1946 as it marked the end of construction of the notable buildings and mausoleums.

Lloyd Brothers Monument Company, based in Toledo, created many of the monuments and mausoleums on the site. It is also one of the oldest monument firms in the country. Lloyd Brothers was established in 1846 and is today one of a few firms that continue to do all of their creations by hand. Lloyd Brothers has done significant architectural work both nationally and regionally. Their work includes the new Toledo Court House, the Fort Meigs battle monument, the Booker T. Washington Monument in Tuskegee, Alabama, and the General Robert E. Lee and Lewis and Clark Monuments in Charlottesville. Woodlawn Cemetery has an unequaled collection of their monuments and mausoleums.

Located in section 41 is the Lucas County Civil War Monument, also constructed by Lloyd Brothers, which commemorates the area’s veterans. The granite monument was dedicated on May 25, 1901, and is 65 feet tall and weighs 32,000 pounds. The architectural design is of a Grecian needle, although it is commonly and incorrectly referred to as Cleopatra’s needle. The memorial is surrounded by 295 graves that at the time of the dedication were of unknown soldiers. Today all except one of the 295 soldiers have been identified; his only identification is the initials F. W. C. on his marker stone. The graves that lay around the base of the monument are laid out in the shape of a five-pointed star, the symbol of the Grand Army of the Republic.

The cemetery contains the graves of several Civil War officers. One notable grave is that of Colonel Henry G. Neubert. Neubert participated in General William Tecumseh Sherman’s "march to the sea" in November 1864. Colonel Neubert’s grave has a bronze bust that weighs between 150-200 pounds. On either side of his grave there is a stone bench. The monument’s stone pedestal has a bronze relief sculpture showing the Colonel on horseback next to General Sherman. They are apparently looking toward Savannah, Georgia, the goal of the march. Neubert thought of the monument design himself (photo #41). James B. Steedman, who fought at Chickamauga during the Civil War and rose to the rank of Major General, is also buried in the cemetery. His monument is a seven-foot tall pedestal upon which a bronze bust of Steedman is perched.

The Gunckel Monument, a pyramid, is a memorial to John Gunckel the founder the Toledo Newsboy Association. The monument was dedicated almost two years after his death on August 11, 1917. It is located a half mile from the Woodlawn Cemetery entrance and overlooks a stream. The pyramid is made of approximately 10,000 small stones and rocks. The stones were contributed by citizens of Toledo and came from all over the world. They include agates from the Holy Land and rare stones from China, Japan, and Alaska. The base of the 1 ton monument is thirty feet in length and the height is 26 feet. The Lloyd Brothers Monument Company (photo #39) did the work on the pyramid.

Just inside the entrance gates sits the unusual and unique monument erected for Bessie Ludwig. The monument features a granite replica of the easy chair upon which Bessie spent the last twenty-five years of her life. After the death of her husband she became a familiar sight reclining in her easy chair. It is reported that she sat and slept in the chair because she feared if she lay down she would never rise again. When Bessie died in 1930 her chair was sent to a Vermont quarry to ensure that an exact replica was carved out. The platform arrived before the chair. Once finished the chair made its journey to Toledo by rail. It was then transferred onto a special car that carried the monument down the trolley line on Central Avenue. A special line was laid from Central, through the gates of the cemetery, so the chair could be transported to its final resting-place. The Lloyd Brothers Company (photo #40) designed the Ludwig monument.

Rural cemeteries were not exclusively for the upper classes and were open to anybody who could purchase a lot. They are graphic registers of social significance and status, having both "fashionable" and "unfashionable" sections. On most occasions poor people could not afford family plots and would instead buy single lots. Normally these lots would be adorned with modest markers. The wealthy were able to purchase spacious lots where they could flaunt their wealth by building impressive mausoleums or monuments. (Ames: 651)

Woodlawn Cemetery reflects the stratification of society in Toledo. The wealthy were able to purchase lots in prime locations along the lakefronts or on elevated areas (photo #1). The lakes are central features in the cemetery, and the existence of social classes can be seen as they radiate outwards from these features. The cheapest lots are found in the most undesirable portions of the cemetery. These tend to be near the boundary fence on land that is less landscaped.

In Woodlawn monuments and mausoleums are strategically placed to complement the scenery. Each monument is constructed according to location and surroundings. Individuality of style is maintained through strict rules concerning the duplication of unique monuments.

Woodlawn Cemetery is an important cultural and historic landmark in the area of landscape architecture and architecture. It has remained dedicated to the rural cemetery movement. The Association continues to emphasize a landscape of natural beauty and ensures that only monuments of high quality and artistic design are erected on the property. The history of Woodlawn Cemetery reflects the development of the rural cemetery movement, and the growth and evolution of Toledo. The cemetery "resolved the cities’ conflict between memory and progress and provided sanctuary and stability in a dynamic, energized age."(Ames: 642)

Major Bibliographical References

Primary Sources

Bibliography files and Scrapbooks. Local History and Genealogy. Toledo-Lucas County Public Library.

Manuscripts, pamphlets, documents, etc. found at Woodlawn Cemetery. Woodlawn Cemetery Association 1876-1996. Most of the material is now at the Canaday Center, University of Toledo.

Proceedings of the Eleventh Annual Convention of American Cemetery Superintendents 1897

Toledo Blade 1910-1990

Woodlawn Cemetery Association. Description of Woodlawn Cemetery (1883)

Glimpses of Woodlawn. Toledo, Oh., c.1883.

Rules and Regulations Handbook.

Secondary Sources

Ames, Kenneth L. "Ideologies in Stone: Meanings in Victorian Gravestones." Journal of Popular Culture 14 (Spring 1981):641-656.

Bender, Thomas. "The Rural Cemetery Movement: Urban Travail and the Appeal of Nature." New England Quarterly 47 (June 1974):196-211.

Bohan, Ruth L. "A Home Away From Home: Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis, and the Rural Cemetery Movement." Prospects 13 (1988):135-179.

Clendaniel, William C. "Rural Cemeteries: Guardians of Our Nation’s Heritage." Cemetery Management, (January 1995):6-11.

Emch, Lucille B. "Two Anniversaries in Toledo, Ohio, in the American Bicentennial Year: The Hundredth for Woodlawn Cemetery and the Seventy-Fifth for the Lucas County Civil War Memorial." Northwest Ohio Quarterly 49 (Spring 1977):43-55.

Firebaugh, Glenn. "The Trees of Woodlawn Cemetery," 1976 Naturalist Yearbook.

French, Stanley. "The Cemetery as Cultural Institution: The Establishment of Mount Auburn and the ‘Rural Cemetery’ Movement." American Quarterly 26 (March 1974):37-59.

Gordon, Stephen C. How to Complete the Ohio Historic Inventory. Columbus: Ohio Historical Society, 1992.

Jeffrey, Linda A. et al. "Toledo’s Historic Woodlawn Cemetery." Northwest Ohio Quarterly 68(Winter 1996):8-22.

Linden-Ward, Blanche and David C. Sloane. "Spring Grove: The Founding of Cincinnati’s Rural Cemetery, 1845-1855." Queen City Heritage 43(Spring 1985): 17-32.

Lockwood, Charles. "As Near to Paradise as one can Reach in Brooklyn, N.Y." Smithsonian 7 (April 1976):56-62.

Porter, Tana Mosier. Toledo Profile: A Sesquicentennial History. Toledo, OH., Toledo Sesquicentennial Commission, 1987.

Sloane, David. The Last Great Necessity: Cemeteries in American History. Baltimore, MD, John Hopkins University Press, 1991

Stannard, David E. "Calm Dwellings: The Brief Sentimental Age of the Rural Cemetery." American Heritage 30 (August 1979):43-54.

Zanger, Jules. "Mount Auburn: The Silent Suburb." Landscape 24 (1980):23-28.

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Akron Rural Cemetery Buildings, Glendale Cemetery, Akron, OH.

Greenwood Cemetery, Hamilton, OH.

Spring Grove Cemetery, Cincinnati OH.

Union Cemetery, Steubenville, OH.

Woodland Cemetery, Cleveland, OH.

Woodland Cemetery, Dayton, OH.

Verbal Boundary Description

Woodlawn Cemetery is situated in Lucas County, Toledo, Ohio. The district consists of 159.14 acres. It is bounded on the north by Hillcrest Avenue and to the south by Central Avenue. Willys marks its eastern limits while Jackman Road marks it western limits.

Boundary Justification

The district selected for nomination consists of 159.14 acres of land known as Historic Woodlawn Cemetery. This is nearly all of the original 160 acres excluding a small portion on the southwestern corner of the cemetery sold to the city when I-475 was constructed.

See also:

Historic Woodlawn Cemetery Website

Woodlawn Cemetery Association Records, MSS-112 (Canaday Center finding aid)