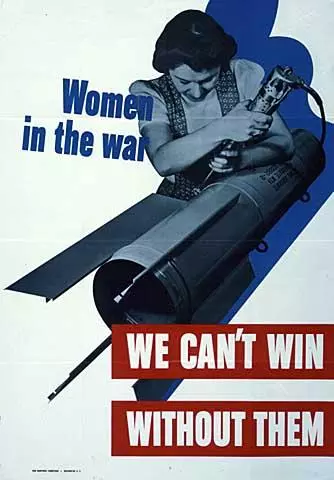

In World War II, Toledo did its part to help the war effort. A silent, but equally important, part of that team was made up of local women who entered the workforce.

Prior to the War

The Great Depression of the 1930s had thrown America into flux. The American family did not escape unscathed as jobs became scarce. With the continual drop in family incomes, which in turn led to a drop in the birth and marriage rates, the battle over the place of woman in the household and her place in the work force raged.

Those women who were in the work force prior to the depression quickly found themselves unemployed. In the instance of the United States federal government, Section 2134 of the Economy Act of 1932 required a massive reduction in the growing government workforce. Although the act did not require it, more than 75% of the workers released were women. But even with the reduction in the government workforce, by the end of the depression the number of women working outside the home actually increased, rising to 25% of the total workforce.

Even though there were gains in the number of women in the workforce, the number of women working in skilled positions remained low. Conservative estimates state that more than one third of employed women worked in the clerical field, with most of the other positions available usually as domestic workers or unskilled labor.

War Time Conversions at Work and Home

The war brought about massive changes for everyone. Automobile manufacturers began producing aircraft engines and tanks, steel workers began producing bullets, and clothing manufacturers began producing uniforms.

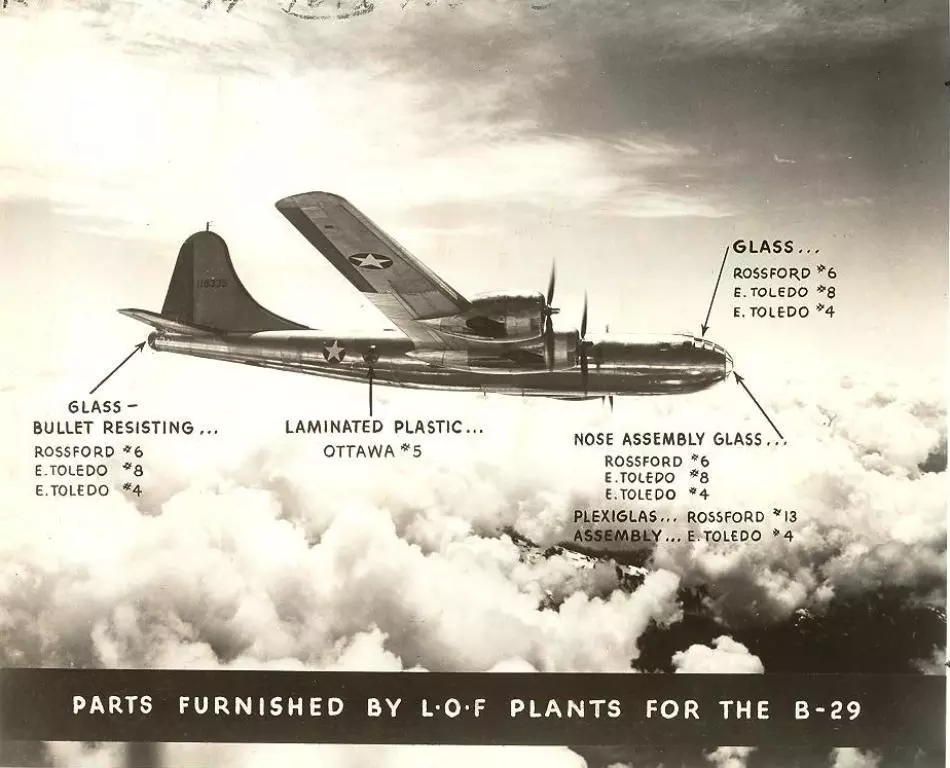

The factories of Toledo were no different during the war. Libbey-Owens-Ford, then a producer of industrial and automobile glass, began manufacturing nose cones and canopies for various military aircraft such as the B-17, B-25, B-29, and P-47.

Another local factory, Acklin Stamping, began a conversion process as well. During the war, Acklin manufactured shell casings for the various large shells used during the war.

On the domestic front, the lives of Americans went through another form of conversion. As husbands went off to fight, non-working wives began to look for work. The government tried to help these working mothers with the passage of the Lanham Act, which created more than 3,100 day care facilities for children of single parent homes.1

Other government initiatives included the creation of the Women's Land Army of the US Crop Corps in 1944. The Women's Land Army asked for women over the age of 18 who could handle manual labor to volunteer or apply for work in various agricultural areas.2

Women who did not join the few branches of the military that allowed women worked in various industries. Although most performed "unskilled" tasks such as farm work or light labor in factories, all were vital to the war effort.

Unions and the War Effort

One major hurdle that women had to overcome was the large union presence in manufacturing. These issues ranged from sexual discrimination in hiring to lower wages, with a large number of male workers believing that a woman’s place was not in the workforce.

As more and more men were drafted into the conflict, this stance had to bend for industry to continue to support the war effort. Even though hostile unions now needed women to take the place of men shipped off to war, they still fought against securing the same rights for females that their male counter-parts enjoyed. Other unions, such as the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks (an AFL union), passed union legislation that was targeted directly at women. In 1943, the Brotherhood passed legislation that required all female laborers to resign upon marriage. This was not a requirement for male workers.3

Wages earned by women were on par with those made by men during the wartime period. If the union did allow women to work at their facility, it was imperative to their own economic survival that women did not earn less than men, as the company could possibly lay off male workers and replace them with cheaper female labor. Union workers saw this happening at shops in Detroit's Hoover Company, Baker Rouland Company, as well as others that had fired male laborers and employed more than 85% women during the war. AFL unions such as the Amalgamated Clothing Workers; the United Auto Workers (UAW); the United Electrical Workers (UEW); and the United Rubber Workers (URW) recognized this, as well as the need to protect their own (male or female), and all pushed for increased female wages as well as equal protection.4

Women at War at Libbey-Owens-Ford

More items on wartime production at Libbey-Owens-Ford can be found at the Ward M. Canaday Center at the University of Toledo in the Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991. These records contain an extensive photograph collection on the conversion of the plant to wartime production, as well as news articles from various local newspapers and memoranda from plant executives on aiding the Allies in World War II. The collection also contains an extensive amount of information on the post war conversion back to non-military production.

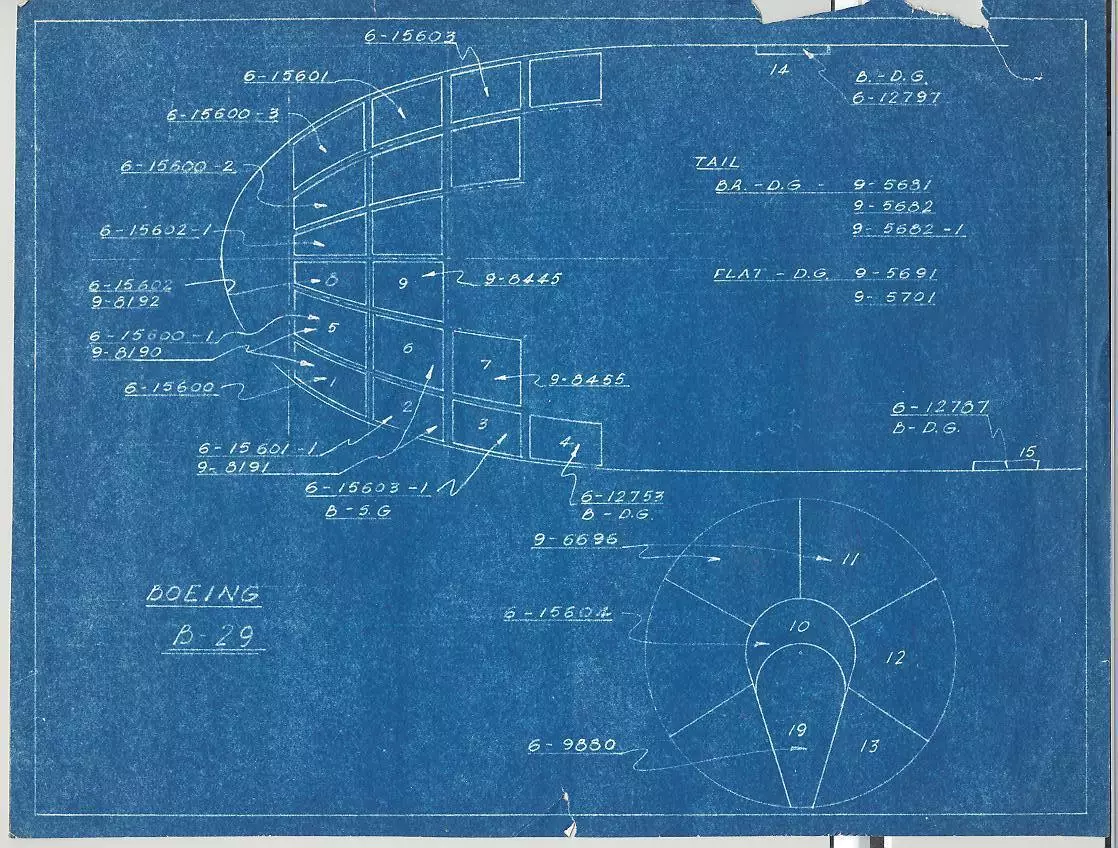

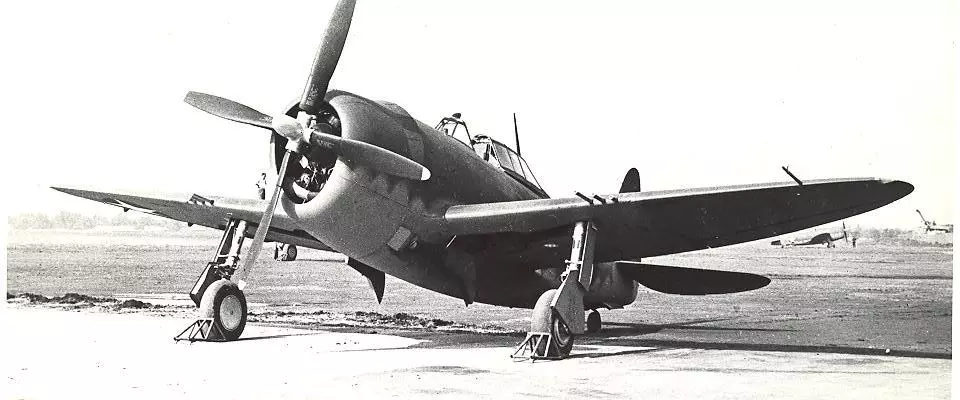

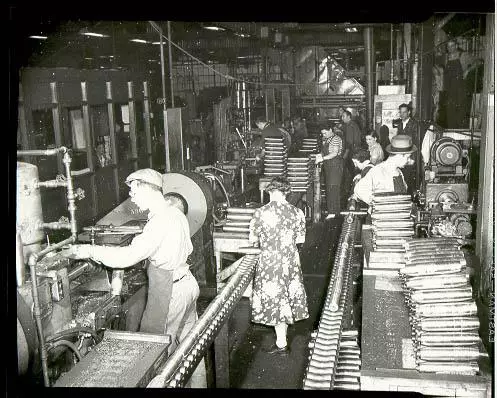

Below are photographs focusing on the role women played in wartime production at the Libbey-Owens-Ford plants in the Toledo area. Included are photographs and schematics for the aircraft that they supplied parts for.

Parts furnished for B-29 (left); Blueprint of the nose of a Boeing B-29 bomber from World War 2 (right)

The “bullet-resistant” windshield for the P-47 Thunderbolt was constructed at the Libbey-Owens-Ford Plant.

The “bullet-resistant” windshield for the P-47 Thunderbolt was constructed at the Libbey-Owens-Ford Plant.

By the war’s end, the plant has built more than 35,000 windshields for the P-47.

Here are a “forest of bubbles,” canopies for the P-47, under inspection prior to shipment to Ottawa, Illinois for final fab (left)

Kate Schmidt (left) and Ann Seman (right), displaying the 5,000th nose cone constructed at the Libbey-Owens-Ford plant (right)

Women at War at Acklin Stamping

Acklin Stamping, now a division of ICE Industries, was also a large contributor to the Toledo war-time effort. Acklin workers were given the responsibility of completing 20, 40, 75, and 105mm shells for various weapons. Other efforts included making parts for Willys-Overland Jeeps, making artillery mounts, and making some of the parts for the atomic weapons dropped on Japan.

More information on Acklin Stamping and its wartime efforts can be found in the Acklin Stamping Company Records, 1911-1997, which can be found at the Ward M. Canaday Center at the University of Toledo. Further information can also be found in the Acklin Stamping Company -- Faces of Steel exhibit by Benjamin Grillot.

There are numerous photographs of women working at the Acklin Stamping plants in Toledo, OH. These women are working on various sizes of munition shells.

Post War

Women in labor at the end of the of war

Women in labor at the end of the of war

By the end of the war, women made up more than 36% of the civilian workforce, up from 25% at the beginning of the conflict. These gains, unlike the “traditional” positions that these women worked, included skilled and white color positions, such as professors, pilots, or scientists. Some of these gains can be traced back to their war time work experiences in plants that had been converted to specialize in munitions or aircraft production.5

Of course, the end of the war brought about changes in the lives of these women. With conservative estimates of 600,000+ dead and 400,000+ wounded soldiers, the lives of these women changed drastically with the end of the conflict. With the return of the troops came the loss of positions that women had taken during the war. Despite the loss of jobs and the return to domestic life for some, the total number of women in the workforce was still at a higher level than in the pre-war period.6 Although a large portion of the women who had worked in factories were no longer in the workplace, they helped begin changing the national opinion on the place of women in the workplace.

In 1948, women were finally allowed to serve in the United States Armed Forces during peacetime. It would not be until 1975 – three decades after they helped win the war – that women would be allowed in the United States military academies.

Endnotes

1. Litoff, Judy Barrett and David C. Smith, ed. American Women at War: Contemporary Accounts from World War II. Scholarly Resources. Wilmington, DE. 1997. Pg. 167.

3. Campbell, D'Ann. Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era. Harvard University Press. Boston, Ma. 1984. pg. 145-146.

5. Hartman, Susan. The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940s. Twayne Publishers. Boston. 1982. pg. 21.

Bibliography and Other Relevant Sites

Aytes, Rosanna. creator. 2006. Women Changed Wartime Work Patterns. El Paso Community College, El Paso, TX. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

Aytes, Rosanna. creator. 2006. Women Changed Wartime Work Patterns. El Paso Community College, El Paso, TX. Retrieved June 14, 2007.

Campbell, D'Ann. Women at War with America: Private Lives in a Patriotic Era. Harvard University Press. Boston, Ma. 1984.

Hartman, Susan M. The Home Front and Beyond: American Women in the 1940's. Twayne Publishers. Boston. 1982.

Litoff, Judy Barrett and David C. Smith, ed. American Women at War: Contemporary Accounts from World War II. Scholarly Resources. Wilmington, DE. 1997.

Phillips, Julieanne "Do the Job He Left Behind: The Cleveland Womanpower Committee, 1943-1945." Ohio History Vol. 109 (Summer-Autumn). 2000. pg. 144-166.

Siegerman, Harriet, ed. The Columbia Documentary History of American Women Since 1941. Columbia University Press. New York. 2003.

Acklin Stamping Company Records, 1911-1997. MSS-139. Ward M. Canaday Center, Carlson Library. The University of Toledo. [Collection Finding Aid]

Libbey-Owens-Ford Glass Company Records, 1851-1991. MSS-066. Ward M. Canaday Center, Carlson Library. The University of Toledo. [Collection Finding Aid]

Grillot, Benjamin, Faces of Steel: People and History of the Acklin Stamping Plant [Virtual exhibition]

Women in Military Service:

An excellent history of the more than 200,000 women who enlisted in the Women’s Army Corps (WAC) can be found here. (Courtesy of the US Army Center for Military History) For a history on the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services (WAVES) during World War II, please click here.

An online collection about WAVES at Oklahoma State University. [Collection in its current location]

For a history of women working in the Weather Bureau during World War II, please see this essay by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

An excellent collection on the The Women Air Force Service Pilots, or WASP, during World War II.

Women in Industry:

A history of women working in skilled military weapon production: http://www.redstone.army.mil