By Timothy Messer-Kruse

February 2002

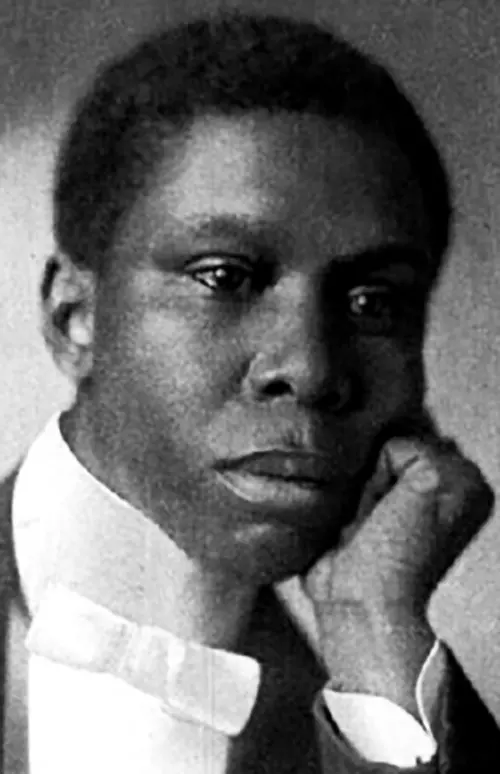

Paul Laurence Dunbar was a young man who witnessed firsthand the fruits of struggle. His father escaped slavery in Kentucky and made his way to Canada through Ohio, and then returned to fight with a Massachusetts regiment against the system that had held him in bondage. His mother fled the memory of her own captivity at the end of the Civil War. From them and others, Dunbar knew the value of action and dreams.

Dunbar applied action and dreams from a young age and excelled in school, advancing to become the only African-American student in the Dayton high school he attended. Though graduating highly, with a well rounded record that included president of the school's literary society, editor of the school newspaper and even having had articles published in the local daily newspaper, the barriers of race in America ordained that upon receiving his diploma Dunbar would be destined to apply his knowledge and training to operating an elevator for a living.

Undeterred by such a fate, Dunbar continued to work on his poetry and in 1892 gave a reading before the Western Association of Writers, then meeting in Dayton. His verses received some notice in local papers in scattered spots around the country, and this favorable response encouraged him to publish his first book, Oak and Ivy, which he did by arranging loans from friends and contracting with a local printing company who took it on with the security of Dunbar's $4 a week job. Oak and Ivy was not a commercial success and Dunbar resorted to hawking copies to the riders in his elevator.

A Helping Hand

In the spring of 1893, Dunbar's self-published book found its way into the hands of a Toledo lawyer, Charles A. Thatcher, who was well read in literature. Thatcher arranged for Dunbar to give a reading before the West End Club, an exclusive literary society with its clubhouse at 1709 Adams Street, where he was a member of the Board of Trustees. Dunbar himself described it as "a very wealthy and aristocratic private club."[1] Though this event proved a turning point in Dunbar's career, it must have been a very uncomfortable evening for the young poet.

Dunbar was not the only man on the evening's schedule. He was preceded by a Dr. W.C. Chapman who, according the Blade ("The West End Club," n. d.), recounted his recent trip to the South and declared "that the old-time feeling of white against black in the south is just as important as it ever was. The blacks are lazy and unambitious in spite of the many educational advantages offered them." Despite such a challenging introduction, Dunbar smashed Chapman's narrow-mindedness with his dignified bearing and overflowing talent. Even the normally subdued business sheet, the Toledo Commercial, was ebullient in its praise of Dunbar's performance that night:

"[Dunbar]…succeeded in astonishing his hearers. Black as the blackest of his race, almost without education, he has still succeeded in producing verses that have the true ring of poetry about them... Besides being a clever writer, Dunbar is an excellent elocutionist, possessing a full, rich and deep voice, which he uses with remarkable discretion. His recitations were received with great favor by the audience." (Toledo Commercial, n.d.n.d.)

It should be noted that the West End Club suspended its normal rules of prohibiting sales in its rooms to allow its members to purchase copies of Oak and Ivy from Dunbar. He sold 28 copies that night (in Dunbar's words "financially…a very successful night"), though not all purchased them for their literary merit alone - Thatcher made a pitch for club members to help pay for Dunbar to go to college through buying his books. (Toledo Blade, Jan 5, 1940).

After this success, Thatcher took the role of Dunbar's patron, writing to him: “I have for some time felt that since nature has endowed you with such gifts that you should have an opportunity of acquiring a thorough education so that you may be fitted for future work" (Apr. 21, 1893). Thatcher offered him $50 per year to enroll in college and helped secure other pledges from Toledoans to supplement his own, badgering university presidents to admit Dunbar for the coming term. He also used his contacts with Toledo papers to get Dunbar's poems in the Toledo Bee and the Toledo Blade. He worked to book Dunbar with the Sunday school Encampment at Lakeside, Ohio (March 29, 1895), a very large annual gathering at that permanent camp meeting resort. Thatcher also extended to the young poet his professional assistance, writing letters on his behalf to an agent who had booked Dunbar for a recitation and never paid.[2] For all this, Thatcher also added a bit of his own, somewhat patronizing, personal wisdom: "You should keep up your work and above all things strive to preserve the modesty which you now possess. You know that the attention you are receiving would turn some persons' heads but I do not think you will fall.” (Apr. 25, 1893)

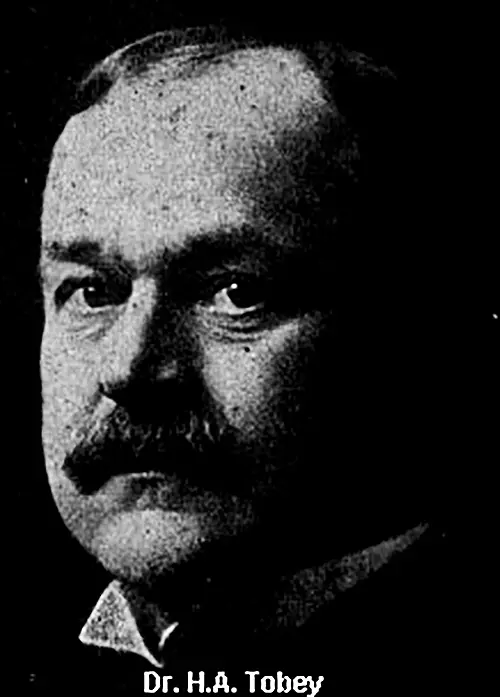

But of all the small favors Thatcher gave to Dunbar, perhaps the greatest was singing Dunbar’s praises to his friend, Henry A. Tobey, the progressive-minded doctor and superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital. In July of 1895, Thatcher wrote Dunbar, "Dr. H.A. Tobey, superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital has become much interested in your welfare and would like to meet you. Please let me know whether you expect to come to Toledo soon..." (July 7, 1895). Tobey would become not only a close friend of Dunbar, but would also play a greater role in his future career than any other person.