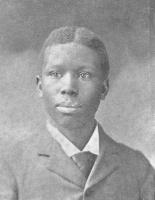

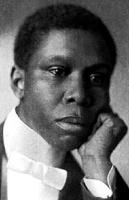

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Exhibit Gallery

By Timothy Messer-Kruse

February 2002

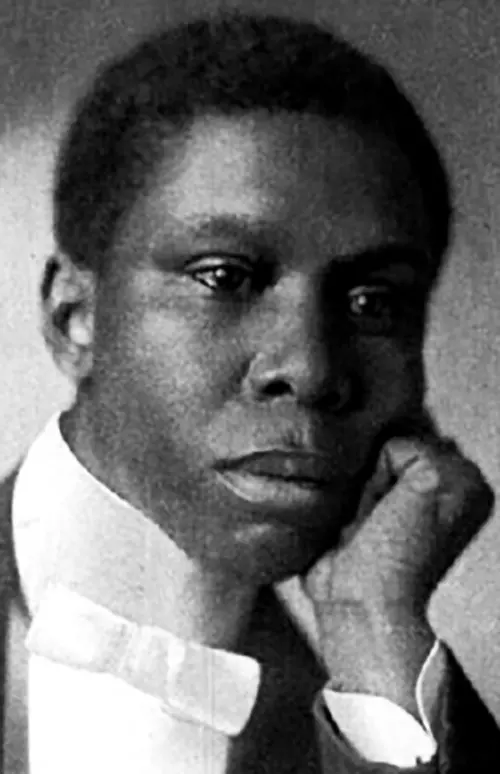

Paul Laurence Dunbar was a young man who witnessed firsthand the fruits of struggle. His father escaped slavery in Kentucky and made his way to Canada through Ohio, and then returned to fight with a Massachusetts regiment against the system that had held him in bondage. His mother fled the memory of her own captivity at the end of the Civil War. From them and others, Dunbar knew the value of action and dreams.

Dunbar applied action and dreams from a young age and excelled in school, advancing to become the only African-American student in the Dayton high school he attended. Though graduating highly, with a well rounded record that included president of the school's literary society, editor of the school newspaper and even having had articles published in the local daily newspaper, the barriers of race in America ordained that upon receiving his diploma Dunbar would be destined to apply his knowledge and training to operating an elevator for a living.

Undeterred by such a fate, Dunbar continued to work on his poetry and in 1892 gave a reading before the Western Association of Writers, then meeting in Dayton. His verses received some notice in local papers in scattered spots around the country, and this favorable response encouraged him to publish his first book, Oak and Ivy, which he did by arranging loans from friends and contracting with a local printing company who took it on with the security of Dunbar's $4 a week job. Oak and Ivy was not a commercial success and Dunbar resorted to hawking copies to the riders in his elevator.

A Helping Hand

In the spring of 1893, Dunbar's self-published book found its way into the hands of a Toledo lawyer, Charles A. Thatcher, who was well read in literature. Thatcher arranged for Dunbar to give a reading before the West End Club, an exclusive literary society with its clubhouse at 1709 Adams Street, where he was a member of the Board of Trustees. Dunbar himself described it as "a very wealthy and aristocratic private club."[1] Though this event proved a turning point in Dunbar's career, it must have been a very uncomfortable evening for the young poet.

Dunbar was not the only man on the evening's schedule. He was preceded by a Dr. W.C. Chapman who, according the Blade ("The West End Club," n. d.), recounted his recent trip to the South and declared "that the old-time feeling of white against black in the south is just as important as it ever was. The blacks are lazy and unambitious in spite of the many educational advantages offered them." Despite such a challenging introduction, Dunbar smashed Chapman's narrow-mindedness with his dignified bearing and overflowing talent. Even the normally subdued business sheet, the Toledo Commercial, was ebullient in its praise of Dunbar's performance that night:

"[Dunbar]…succeeded in astonishing his hearers. Black as the blackest of his race, almost without education, he has still succeeded in producing verses that have the true ring of poetry about them... Besides being a clever writer, Dunbar is an excellent elocutionist, possessing a full, rich and deep voice, which he uses with remarkable discretion. His recitations were received with great favor by the audience." (Toledo Commercial, n.d.n.d.)

It should be noted that the West End Club suspended its normal rules of prohibiting sales in its rooms to allow its members to purchase copies of Oak and Ivy from Dunbar. He sold 28 copies that night (in Dunbar's words "financially…a very successful night"), though not all purchased them for their literary merit alone - Thatcher made a pitch for club members to help pay for Dunbar to go to college through buying his books. (Toledo Blade, Jan 5, 1940).

After this success, Thatcher took the role of Dunbar's patron, writing to him: “I have for some time felt that since nature has endowed you with such gifts that you should have an opportunity of acquiring a thorough education so that you may be fitted for future work" (Apr. 21, 1893). Thatcher offered him $50 per year to enroll in college and helped secure other pledges from Toledoans to supplement his own, badgering university presidents to admit Dunbar for the coming term. He also used his contacts with Toledo papers to get Dunbar's poems in the Toledo Bee and the Toledo Blade. He worked to book Dunbar with the Sunday school Encampment at Lakeside, Ohio (March 29, 1895), a very large annual gathering at that permanent camp meeting resort. Thatcher also extended to the young poet his professional assistance, writing letters on his behalf to an agent who had booked Dunbar for a recitation and never paid.[2] For all this, Thatcher also added a bit of his own, somewhat patronizing, personal wisdom: "You should keep up your work and above all things strive to preserve the modesty which you now possess. You know that the attention you are receiving would turn some persons' heads but I do not think you will fall.” (Apr. 25, 1893)

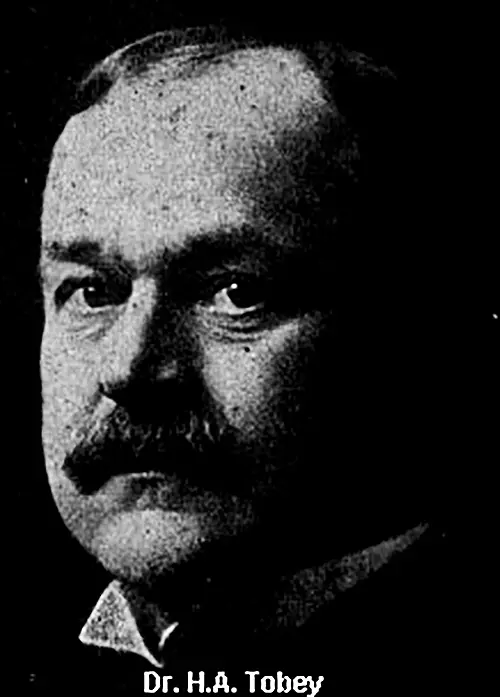

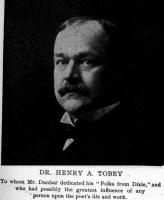

But of all the small favors Thatcher gave to Dunbar, perhaps the greatest was singing Dunbar’s praises to his friend, Henry A. Tobey, the progressive-minded doctor and superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital. In July of 1895, Thatcher wrote Dunbar, "Dr. H.A. Tobey, superintendent of the Toledo State Hospital has become much interested in your welfare and would like to meet you. Please let me know whether you expect to come to Toledo soon..." (July 7, 1895). Tobey would become not only a close friend of Dunbar, but would also play a greater role in his future career than any other person.

A Local Toledo Sensation

Dr. Henry Tobey took on a difficult job when he agreed to head the newly built Toledo State Hospital in 1885. This facility for the mentally ill was the first of its kind in America to break with the cell-like, prison environment of previous public hospitals of its kind. Instead of a central building that housed all the inmates, Toledo State Hospital was designed as a complex of cottages surrounding shared dining halls. As stated in the hospital's annual report, "We have sought in the construction to eliminate so far as possible all the prison-like appearances so prevalent in the old-style hospitals, and in treatment to substitute kindness for force, and to omit to the farthest extent possible all restraints, and to give our people all the amusements we could devise." Laudable ideals indeed, though how they actually fared alongside the daunting task of running a hospital for 1,000 patients whose main illnesses were poorly understood and mostly untreatable is not well documented.

Tobey's interest in Dunbar seemed to grow out of both his recognition of Dunbar's immense talent and his political interest in overcoming racial prejudice. It was Tobey who first raised the issue of race in a letter to Dunbar:

"When I first received your book I learned from the donor that, in a biblical sense, God Almighty has placed the stamp of Cain upon you, or, in other words, your skin is black...I am so thoroughly Democratic in my sentiments that race or condition with me ‘cuts but little figure’ in my estimation of men." (July 6, 1895)

Tobey invited Dunbar to the State Hospital to read for his patients in the spring of 1895. One of the stories told about that visit, though it cannot be firmly documented, is that Tobey sent a carriage to the Toledo railroad station to pick up Dunbar and waited with Charles Cotrill, a prominent member of Toledo's African-American community, for it to return. When Dunbar stepped down from the coach, Tobey exclaimed, "Thank God, he's black!" Cottrill was properly offended, and Tobey tried to save his embarrassment by saying, "Whatever genius he may have cannot be attributed to the white blood he may have in him," a comment that probably did not help much with the lighter-skinned Cottrill.

But Tobey's literary appreciation did seem sincere as well. "I believe you possess real poetical instinct," Tobey wrote:

"In these modern times, when it seems the chief aim and object of man is to obtain the Almighty Dollar, poets and poetry are below par and by the common mass of mankind their real intrinsic value is not appreciated. This condition of society I very much deplore, as I look upon poetry as only a higher philosophy: so subtle, so ethereal, so divine, that our creator has endowed only a few of our kind with the sacred trust of translating to the masses a representation of the joys and sorrows that every heart has felt….I have read your poems again and again, and the more I read them the more I recognize the divinity that stirs within you." (July 6, 1895)

Like Thatcher, Tobey felt compelled to offer Dunbar some unsolicited advice, saying, "When I was in Dayton I learned that your ambition is to become a lawyer. The world is already too full of lawyers for its good, peace or welfare. What we need is [sic] more persons to interpret Nature and Nature's God."

Along with his first letter, Tobey enclosed a check for $5.00, a seemingly small sum to us today, but an amount that made a world of difference for Dunbar at the time. Dunbar himself explained what this meant to him:

"The time for the meeting of the Western Association of Writers was at hand. I am a member and thought that certain advantages might come to me by attending. All day Saturday and all day Sunday I tried every means to secure funds to go. I tried every known place, and at last gave up and went to bed Sunday night in despair. But strangely I could not sleep, so about half-past eleven, I arose and between then and 2 A.M., wrote the paper which I was booked to read at the Association. Then, still with no suggestion of any possibility of attending the meeting, I returned to bed and went to sleep about four o'clock. Three hours later came your [Tobey's] letter with the check that took me to the desired place."

While in Toledo in the spring of 1895, Henry A. Tobey solicited enough pledges of support to offer Dunbar money to attend college. Dunbar wrote to his mother immediately afterwards. "Dr. Tobey and his friends want to lend me 400 or 500 dollars to spend a year in Boston at Harvard. I am going to take it."[3]

Toledo State Hospital's Amusement Hall where Tobey asked Dunbar to read

Toledo State Hospital's Amusement Hall where Tobey asked Dunbar to read

In the fall of 1895, Tobey again invited Dunbar to Toledo to read at the State Hospital. This reading was, by many accounts, a triumph. One can only imagine the scene: the crowded "amusement hall" of patients, some disturbed, some perhaps murmuring, attendants scurrying about trying to maintain decorum, invited dignitaries and guests seated separately, an atmosphere tense and heavy with pathos. A piano off to one side, played by Tobey's talented young daughter Alice. It was an evening with such emotional power for Dunbar that it prompted him to compose a poem on the spot. He is reported to have remembered the evening this way:

"…while in Toledo, Ohio, I consented to recite at an entertainment given for the Insane. Before the recital, I requested the organist to play for me cardinal Necoman's favorite hymn, "Lead Kindly Light." The music and words, rushed through my brain in so maddening a way, blinding me to all outside influences, surging through my very heart and soul, until I could stand it no longer. I rushed off to my room, jotted down the very words of this poem, "Lead gently". When I returned to the recital to take the place assigned me on the program, I brought with me my newly fledged poem and read it before the audience." (Nov. 25, 1897)

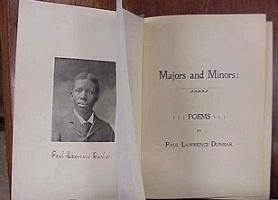

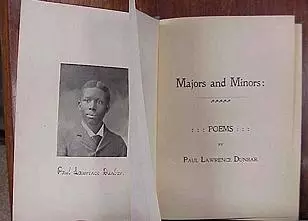

"Majors and Minors" by Paul Laurence Dunbar

"Majors and Minors" by Paul Laurence Dunbar

After this momentous evening, in conversation with his Toledo hosts, Tobey and Thatcher, Dunbar expressed his wish to publish a second book on his own as he did his first. Tobey and Thatcher immediately offered to underwrite the publication on terms that were far more favorable than what the Dayton printer had given Dunbar for Oak and Ivy. With Tobey and Thatcher's help, Dunbar's new book, to be titled Majors and Minors, was contracted with Hadley & Hadley Printing Co. Hadley and Hadley was not the largest printer in Toledo; they operated out of four floors of a building at 136 Superior St. that was located next to a feed lot. Most of its business seemed to be in catalogue and poster printing and a literary book was probably a first for the firm. Perhaps it was chosen because its owners were known as "enterprising and progressive business men" and the company a "progressive one." Though everyone struggled to get out the 1,000 copies before Christmas in 1895, the book appeared a few months later.

Henry Tobey, acting more like the author than the producer, was so eager to get hold of the new poems in printed form that he went to Hadley and Hadley's office, grabbed an unbound volume, and began cutting away pages with his pocket knife. After Majors and Minors was printed, Dunbar tried to sell his books in Toledo, but met with great resistance, as most whites considered him a salesman or agent. Tobey tried to shield his friend from his failure as a salesman and apparently sold copies in advance to friends with instructions to pretend to buy the copies from Dunbar.

The Toledo "Discovery"

Dunbar spent a good deal of time in Toledo in the spring of 1896. Things were not looking very cheery, however - he hated having to hawk his own books. He wrote to his future wife, Alice Ruth Moore, from the city:

"This rainy Sunday finds me still lingering in Toledo - idly busy, lazily industrious. On the last few days, the sun has kissed the face of April into smiles and blushes, - but today she is back at her old tricks of weeping and sulking, like a petulant maiden. And I am like the day, full of moods and changing feelings, now sad, now pensive, now gay. Just at present there is not much gayety in me. The clouds and the wind and the rain depress me."[4]

But while Dunbar lingered, Henry Tobey's enthusiasm for Dunbar's verse proved infectious. The day Tobey received his first finished copy of Majors and Minors, he happened to be staying overnight in a downtown hotel after being called into the city on business, where he met a friend interested in poetry. Together, they sat up reading the poems until almost midnight. Stopping at the desk for their room keys later, they bumped into James O'Neal and his wife and a Mr. Nixon who were acting in "Monte Christo," then appearing on the stage at Toledo's newly opened Valentine Theater. O'Neal went to his room, but Nixon stayed, and Tobey urged him to read some of the poems. At first, Nixon read quietly over the hotel desk, then read "When Sleep Comes Down to Soothe the Weary Eyes" aloud and gave a dramatic recitation in the hotel lobby! The two pored over the poems together until the early hours of the morning, and Nixon pronounced that no one had written such verses since Poe.

This lobby literary spectacle led to a copy of Majors and Minors falling into the hands of the playwright James Herne, who happened to be in town to oversee production of his play “Shore Acres.” It was the Boody Hotel's desk clerk who made sure Herne was given a copy. Herne wrote Dunbar immediately from his next theatrical stop in Detroit:

MY DEAR MR. DUNBAR:

While at Toledo, a copy of your poems was left at my hotel by a Mr. Childs. I tried very hard to find Mr. Childs to learn more of you. Your poems are wonderful. I shall acquaint William Dean Howells and other literary people with them. They are new to me and they may be to them. I send you by this mail some things done by my daughter, Julia A. Herne. She is at school in Boston. Her scribblings may interest you. I would like your opinion….

I am an actor and dramatist. My latest work - "Shore Acres" you may have heard of. If it your way, I want you to see it, whether I am with it or not. How I wish I knew you personally! I wish you all the good fortune that you can wish for yourself.

Yours very truly,

James A. Herne.

Herne did indeed send a copy of Majors and Minors to William Dean Howells, the former editor of the influential Atlantic Monthly, famed literary critic, and acclaimed "modern" novelist. This was Dunbar's big break. Few literary figures had the contacts or the influence that Howells commanded in the 1890s. Howells assessment of Dunbar's work was that it was sublime, and Howells eventually let everyone know of "his" discovery.

In the meantime, Dr. Tobey, who traveled widely for professional conferences, energetically introduced reporters and critics to Dunbar’s' works. He introduced the editor and author Robert G. Ingersoll to Dunbar's works:

"I know you are too busy a man to read all the poems in this book, so I take the liberty of marking a number which I consider the stronger ones. I do not profess to be literary, but think I probably have ordinary human feeling and common sense, and I would like you to read over the poems I have marked, and which I think unusual. If after reading them you feel the same way, it would be great consolation to Mr. Dunbar in his poverty and obscurity if you would write a letter of commendation."

To which Ingersoll replied:

No. 220 Madison Ave.

April, 1896, New York City

MY DEAR DR. TOBEY:

At last I got the time to read the poems of Dunbar. Some of them are really wonderful - full of poetry and philosophy. I am astonished at their depth and subtlety. Dunbar is a thinker. "The Mystery" is a poem worthy of the greatest. It is absolutely true, and proves that its author is a profound and thoughtful man. So the "Dirge" is very tender, dainty, intense and beautiful. "Ere Sleep Comes Down to Soothe the Weary Eyes" is a wonderful poem: the fifth verse is perfect. So "He Had His Dream" is very fine and many others.

I have only time to say that Dunbar is a genius. Now, I ask what can be done for him? I would like to help.

Thanking you for the book, I remain.

Yours always,

R.G. Ingersoll

Howell’s review of Majors and Minors appeared in Harper's Weekly, one of the largest circulating magazines in the nation. It coincidentally came out in the same issue that featured a report on the nomination of William McKinley and therefore boasted a larger than normal circulation. The issue was dated June 27, 1896 – Dunbar's 24th birthday. Dunbar bought a copy from a Dayton newsstand and as he stood there in the street he was overcome with emotion. Around this time his mother was away from the house for a time and when she returned found a pile of some two hundred letters for her son.

From this point on, Dunbar's fame was never in doubt. He was soon overwhelmed with invitations to write for leading papers and journals and make personal appearances. By 1898, it was reported that he was earning over $3,000 a year with his pen.

Claiming Credit for Celebrity

After the Harper's success, Tobey again invited Dunbar to Toledo for a series of readings at the Asylum near the Fourth of July (as holidays are so difficult for the institutionalized). Without telling his guest, Tobey invited dozens of dignitaries, including the Governor of Ohio, Charles Foster, who said later, "Of all things I have ever heard, I never listened to anything so impressive as his rendition of the "Ships that Pass in the Night." Like the previous time Dunbar appeared in the Asylum, he was inspired to write an original poem on the occasion, and on that night he wrote his poem "The Crisis."

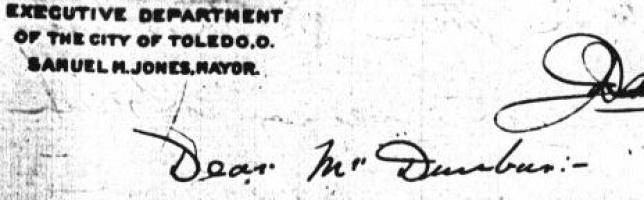

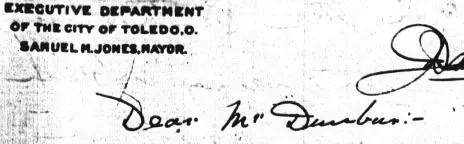

Toledo Mayor Samuel Jones's letter to Dunbar

Toledo Mayor Samuel Jones's letter to Dunbar

As Dunbar's star rose, he remained close to Toledo and made friends with the low and the high of Toledo society. He made an especially firm impression with Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones and with his literary and political protégé, Brand Whitlock. Of course, these reformers tried to push Dunbar into their own streams. Jones urged Dunbar to take up the mantle of the reformer: "I yet hope to hear you sing for the disinherited and downtrodden millions black and white as Lowell and Whittier sang for the black slaves 50 years ago" (December 12, 1898). Whitlock, meanwhile, plied Dunbar with suggestions that he write more about the injustice of capital punishment (December 5, 1900)

Henry A. Tobey continued his knack for lending a helping hand when it was most needed. When, after a lengthy English tour in 1897, Dunbar found himself short of funds for the return passage home, Tobey wired the necessary amount. When Dunbar sought relief from tuberculosis in the mountain air of Colorado, Tobey wrote to a fellow physician in Denver (July 25, 1899) and arranged for Dunbar to receive the doctor’s hospitality and free medical attention (July 31, 1899).

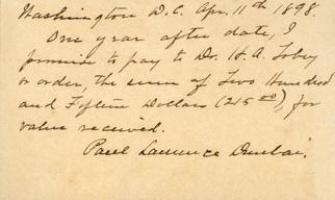

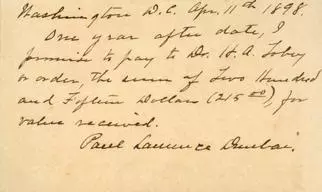

An I.O.U. Written out by Dunbar

An I.O.U. Written out by Dunbar

The relationship between Tobey and Dunbar was a complex one. Dunbar was not only close to Tobey but to Tobey’s entire family. When Dunbar visited Toledo, he often stayed at the Tobeys’ home and enjoyed playing with their children. On one occasion, as Dunbar revealed, this caused him some trouble:

"The girls…and I have been having a jolly good time and they had powdered me and black my eyebrows and under my eyes, - it was lots of fun at the time, but merciful heavens! I forgot to remove it before the company came, and here I sit writing with my head bowed low in order to conceal my shame, just waiting for a chance to make a break for my room."[5]

Tobey continually viewed himself as a father to Dunbar and, in some ways, the poet seemed to have reciprocated. When Dunbar suddenly married his sweetheart in 1898, he wrote Tobey: "I am married! I would have consulted you, but the matter was very quickly done…I hope you will not think I have been too rash." Tobey responded and gave his blessing to the union, though added that he would have preferred the young man have cleared up all his debts before wedding. But this was enough reassurance for Dunbar, who seemed relieved: "I was very glad to get your letter and find that you did not think ill of my step. I must confess I was very anxious as to how you would take it."[6] That year Dunbar dedicated his book Folks from Dixie to Henry Tobey.[7] But Dunbar also hints at a more conflicted and forced relationship as well, saying in one letter that he had to be "deceitful and smiling and affable" in the company of Toledo friends.[8]

He made many appearances in the city over the next decade, including a performance at the request of Mayor Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones at his Golden Rule Hall in 1898 (December 12, 1898). That same year, Dunbar attracted an audience of over one thousand to the City Hall in Bowling Green, Ohio. "No purely literary entertainment in Bowling Green was ever larger attended," observed one reporter, "and none received as unqualified endorsement of hearty approval."

As Dunbar's health deteriorated after 1902, his friends in Toledo stayed in touch and wrote him encouraging letters. (Apr. 30, 1902) Henry Tobey in particular expressed a deep sympathy with Dunbar's worsening condition, as his own health declined along with his career, the later apparently shaken by partisan political attacks and accusations of corruption. In early 1906, word arrived in Toledo that Dunbar's condition had become very grave. Brand Whitlock and John Mockett made plans to travel to Dayton and visit the dying poet. On Feb. 6, 1906, Henry Tobey wrote a long, dark, rambling letter explaining the shambles his own life was in, proclaiming at one point, " Poor Boy, you are resting easy. Wish you had to fight like I do. You would forget you ever had what someone called Tuberculosis….you poor black discouraged dying wretch, I envy you." Dunbar never read these depressing sentiments, as he died the day they were mailed.

Endnotes

[1] Dunbar Papers, Dunbar to James Newton Matthews, May 2, 1893 (Ohio Historical Society).

[2] The Shearer Musical and Lecture Bureau of Cincinnati had contracted with Dunbar to tour with a musical company and give recitations for $25.00 a week and apparently reneged on the offer. Thatcher advised Dunbar on his rights and wrote to Shearer directly on his behalf. (Dunbar Papers, Dunbar to James Newton Matthews, Apr. 30, 1894 (Ohio Historical Society).

[3] Dunbar Papers, Dunbar to Matilda Dunbar, Aug. 18, 1895 (Ohio Historical Society).

[4] Dunbar Papers, Dunbar to Alice Ruth Moore, Apr. 19, 1896 (Ohio Historical Society).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Dunbar Papers, Dunbar to Henry A. Tobey, undated, 1898 and Apr. 6, 1898 (Ohio Historical Society).

[7] Paul Laurence Dunbar, Folks from Dixie (New York: Dodd, Mead and Co., 1898).

[8] Dunbar Papers, Dunbar to Alice Ruth Moore, Apr. 19, 1896 (Ohio Historical Society).

Articles Written About Paul Dunbar From Local Newspapers

Poem by J.N. Mockett entitled, "Paul Lawrence Dunbar," Toledo News-Bee, Dec. 13, 188?/1898?.

"Dunbar Heard Again: Recital of Clever Lyrics: The Colored Bard Charms a Toledo Audience..." Source unidentified, n. d.

"Successful was the Paul Laurence Dunbar Recital: A Large Attendance and Hearty Approval...", The Daily (Bowling Green), n. d.

"Paul Dunbar Heard: Gives a Private Recital: The Colored Poet Entertains Dr. and Mrs. Tobey..." Source unidentified, n. d.

"Paul Dunbar's Reading: Excellent Entertainment Given at State Hospital", Toledo Blade,.n. d.

"(P.L. Dunbar) At the Auditorium last evening...", Toledo Blade, Dec. 13, 1898.

"Paul Dunbar's Reading." Toledo Evening News, Dec. 13, 1898.

"The West End Club: An Interesting Meeting Held Last Night", Toledo Blade, n. d.

(P.L. Dunbar at the West End Club), Toledo Commercial, n. d.

List of Toledo Letters

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Apr. 21, 1893 [PDF]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Apr. 25, 1893 [PDF]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Dec. 1, 1894 [PDF]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Dec. 9, 1894 [PDF]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Dec. 12, 1894 [JPEG/image]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Mar. 29, 1895 [PDF]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, July 6, 1895 [PDF]

PLD to H.A. Tobey, July 13, 1895 [PDF/transcription only]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, July 7, 1895 [JPEG/image]

Hadley and Hadley Co. to PLD, Dec. 9, 1895 [JPEG/image]

Hadley and Hadley Co. to PLD, Dec. 22, 1895 [JPEG/image]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, Dec. 29, 1895 [PDF]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, Apr. 22, 1896 [PDF]

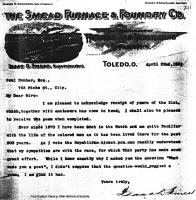

Isaac Smead to PLD, Apr. 22, 1896 [JPEG/image]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, n.d.; partial letter #210 [no facsimile available]

A.A. Jennings to PLD, Apr. 20, 1896 [JPEG/image]

Chas. A. Thatcher to PLD, Jan. 17, 1897 [PDF]

D.K.B. to NY Tribune, Nov. 25, 1897 [PDF]

S.M. Jones to PLD, Dec. 12, 1898 [PDF]

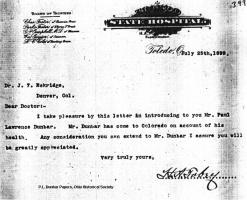

H.A. Tobey to Dr. J.T. Eskridge, July 25, 1899 [JPEG/image]

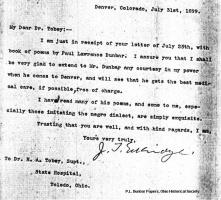

J.T. Eskridge to H.A. Tobey, July 31, 1899 [JPEG/image]

Brand Whitlock to PLD, Dec. 5, 1900 [PDF]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, Apr. 30, 1902 [PDF]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, June 10, 1902 [JPEG/image]

Brand Whitlock to PLD, July 20, 1903 [PDF]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, n.d.; partial letter #775 [JPEG/image]

H.A. Tobey to PLD, Feb. 5, 1906 [PDF]

All Dunbar correspondence reproduced with the permission of the Ohio Historical Society.

Acknowledgments

This exhibit was made possible with the help of Cynthia Ghering of the Ohio Historical Society; the Wright State University Library and Special Collections and Archives; the Toledo Lucas County Public Library Local History Room; the Canaday Center for Special Collections at the Carlson Library, University of Toledo. All documents used with the permission of the Ohio Historical Society, the Wright State University Libraries, or the Canaday Center of the Carlson Library.

See also:

Explore the University of Toledo Library Collection: Works by or related to Paul Laurence Dunbar