A Local Toledo Sensation

Dr. Henry Tobey took on a difficult job when he agreed to head the newly built Toledo State Hospital in 1885. This facility for the mentally ill was the first of its kind in America to break with the cell-like, prison environment of previous public hospitals of its kind. Instead of a central building that housed all the inmates, Toledo State Hospital was designed as a complex of cottages surrounding shared dining halls. As stated in the hospital's annual report, "We have sought in the construction to eliminate so far as possible all the prison-like appearances so prevalent in the old-style hospitals, and in treatment to substitute kindness for force, and to omit to the farthest extent possible all restraints, and to give our people all the amusements we could devise." Laudable ideals indeed, though how they actually fared alongside the daunting task of running a hospital for 1,000 patients whose main illnesses were poorly understood and mostly untreatable is not well documented.

Tobey's interest in Dunbar seemed to grow out of both his recognition of Dunbar's immense talent and his political interest in overcoming racial prejudice. It was Tobey who first raised the issue of race in a letter to Dunbar:

"When I first received your book I learned from the donor that, in a biblical sense, God Almighty has placed the stamp of Cain upon you, or, in other words, your skin is black...I am so thoroughly Democratic in my sentiments that race or condition with me ‘cuts but little figure’ in my estimation of men." (July 6, 1895)

Tobey invited Dunbar to the State Hospital to read for his patients in the spring of 1895. One of the stories told about that visit, though it cannot be firmly documented, is that Tobey sent a carriage to the Toledo railroad station to pick up Dunbar and waited with Charles Cotrill, a prominent member of Toledo's African-American community, for it to return. When Dunbar stepped down from the coach, Tobey exclaimed, "Thank God, he's black!" Cottrill was properly offended, and Tobey tried to save his embarrassment by saying, "Whatever genius he may have cannot be attributed to the white blood he may have in him," a comment that probably did not help much with the lighter-skinned Cottrill.

But Tobey's literary appreciation did seem sincere as well. "I believe you possess real poetical instinct," Tobey wrote:

"In these modern times, when it seems the chief aim and object of man is to obtain the Almighty Dollar, poets and poetry are below par and by the common mass of mankind their real intrinsic value is not appreciated. This condition of society I very much deplore, as I look upon poetry as only a higher philosophy: so subtle, so ethereal, so divine, that our creator has endowed only a few of our kind with the sacred trust of translating to the masses a representation of the joys and sorrows that every heart has felt….I have read your poems again and again, and the more I read them the more I recognize the divinity that stirs within you." (July 6, 1895)

Like Thatcher, Tobey felt compelled to offer Dunbar some unsolicited advice, saying, "When I was in Dayton I learned that your ambition is to become a lawyer. The world is already too full of lawyers for its good, peace or welfare. What we need is [sic] more persons to interpret Nature and Nature's God."

Along with his first letter, Tobey enclosed a check for $5.00, a seemingly small sum to us today, but an amount that made a world of difference for Dunbar at the time. Dunbar himself explained what this meant to him:

"The time for the meeting of the Western Association of Writers was at hand. I am a member and thought that certain advantages might come to me by attending. All day Saturday and all day Sunday I tried every means to secure funds to go. I tried every known place, and at last gave up and went to bed Sunday night in despair. But strangely I could not sleep, so about half-past eleven, I arose and between then and 2 A.M., wrote the paper which I was booked to read at the Association. Then, still with no suggestion of any possibility of attending the meeting, I returned to bed and went to sleep about four o'clock. Three hours later came your [Tobey's] letter with the check that took me to the desired place."

While in Toledo in the spring of 1895, Henry A. Tobey solicited enough pledges of support to offer Dunbar money to attend college. Dunbar wrote to his mother immediately afterwards. "Dr. Tobey and his friends want to lend me 400 or 500 dollars to spend a year in Boston at Harvard. I am going to take it."[3]

Toledo State Hospital's Amusement Hall where Tobey asked Dunbar to read

Toledo State Hospital's Amusement Hall where Tobey asked Dunbar to read

In the fall of 1895, Tobey again invited Dunbar to Toledo to read at the State Hospital. This reading was, by many accounts, a triumph. One can only imagine the scene: the crowded "amusement hall" of patients, some disturbed, some perhaps murmuring, attendants scurrying about trying to maintain decorum, invited dignitaries and guests seated separately, an atmosphere tense and heavy with pathos. A piano off to one side, played by Tobey's talented young daughter Alice. It was an evening with such emotional power for Dunbar that it prompted him to compose a poem on the spot. He is reported to have remembered the evening this way:

"…while in Toledo, Ohio, I consented to recite at an entertainment given for the Insane. Before the recital, I requested the organist to play for me cardinal Necoman's favorite hymn, "Lead Kindly Light." The music and words, rushed through my brain in so maddening a way, blinding me to all outside influences, surging through my very heart and soul, until I could stand it no longer. I rushed off to my room, jotted down the very words of this poem, "Lead gently". When I returned to the recital to take the place assigned me on the program, I brought with me my newly fledged poem and read it before the audience." (Nov. 25, 1897)

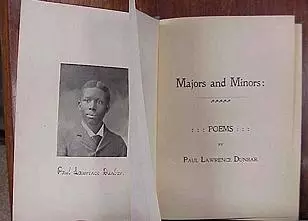

"Majors and Minors" by Paul Laurence Dunbar

"Majors and Minors" by Paul Laurence Dunbar

After this momentous evening, in conversation with his Toledo hosts, Tobey and Thatcher, Dunbar expressed his wish to publish a second book on his own as he did his first. Tobey and Thatcher immediately offered to underwrite the publication on terms that were far more favorable than what the Dayton printer had given Dunbar for Oak and Ivy. With Tobey and Thatcher's help, Dunbar's new book, to be titled Majors and Minors, was contracted with Hadley & Hadley Printing Co. Hadley and Hadley was not the largest printer in Toledo; they operated out of four floors of a building at 136 Superior St. that was located next to a feed lot. Most of its business seemed to be in catalogue and poster printing and a literary book was probably a first for the firm. Perhaps it was chosen because its owners were known as "enterprising and progressive business men" and the company a "progressive one." Though everyone struggled to get out the 1,000 copies before Christmas in 1895, the book appeared a few months later.

Henry Tobey, acting more like the author than the producer, was so eager to get hold of the new poems in printed form that he went to Hadley and Hadley's office, grabbed an unbound volume, and began cutting away pages with his pocket knife. After Majors and Minors was printed, Dunbar tried to sell his books in Toledo, but met with great resistance, as most whites considered him a salesman or agent. Tobey tried to shield his friend from his failure as a salesman and apparently sold copies in advance to friends with instructions to pretend to buy the copies from Dunbar.