Valentine Theatre Symbol

Valentine Theatre Symbol

By Timothy Messer-Kruse, University of Toledo, 1998

In its pioneer decades, Toledo was, not surprisingly, a theatrical backwater. It was not until 1850 that Toledo built a public hall suitable for stage performances and was quickly disappointed to learn that the great singer, Jenny Lind would not travel to Toledo, even for the vast sum of $1,000 a night. By the Civil War Toledo boasted three theaters (Morris Hall, Stickney Hall, and White's Hall). Except for White's Hall, which for a few years in the early 1870s pulled in expensive name acts, none of these were particularly reputable. Stickney Hall was renamed the "Opera House" after the war and included a free drink with the price of admission. By 1875 White's had gone to vaudeville to compete with two new theaters, the Wheeler's Opera House and the Adelphi. However, even the city's workers' growing appetite for regular, inexpensive, ribald fare could not support them all. By the 1890s only Wheeler's and the new People's Theater were still in operation. Toledo's high-brow newspaper, the Blade, complained constantly about the fact that first-rate productions were offered only occasionally alongside the "trashiest kind of trash", that is, the popular farces and melodramas of the day. (Marion S. Revett, "The Old Stage Door", in Northwest Ohio Quarterly, 23:3 (Summer 1951), pp.152-157)

By the 1890s, Toledo had begun to change from a regional center of shipping and trade into a manufacturing center. The city's upper class was growing as fortunes were being made in wholesaling, oil refining, bicycles, wagon-making, glass, and machinery. When Wheeler's Opera House burned down on St. Patrick's Day in 1893, the time was right for the city's elite to build a first-class theater that would allow them to display their newfound wealth. The race was on among the city's leading capitalists to glorify themselves by building a new opera house. Wheat king, Col. Sheldon C. Reynolds was first to announce his intention to build a theater. A few months later coffee king, Alvin M. Woolson, picked out a site and hired architects for his opera palace at St. Clair and Jackson streets. But curiously, when George Ketcham, a man young enough to the grandson of either Reynolds or Woolson, announced that he planned to build an opera house at the corner of St. Clair and Adams, the older men gracefully bowed out. Perhaps the fact that Ketcham had inherited a million dollars from his father five years before scared them off - while Reynolds and Woolson arranged a syndicate to raise financing for their ventures, there was no question as to the source of Ketcham's financing. Ketcham already had a head start as the site he had chosen adjoined, and was partly surrounded by the commercial building he had begun erecting the year before. (Norma F. Stolzenbach, "Toledo Theater", in Randolph C. Downes Industrial Beginnings, (Toledo: Historical Society of Northwestern Ohio, 1954), pp.366-410)

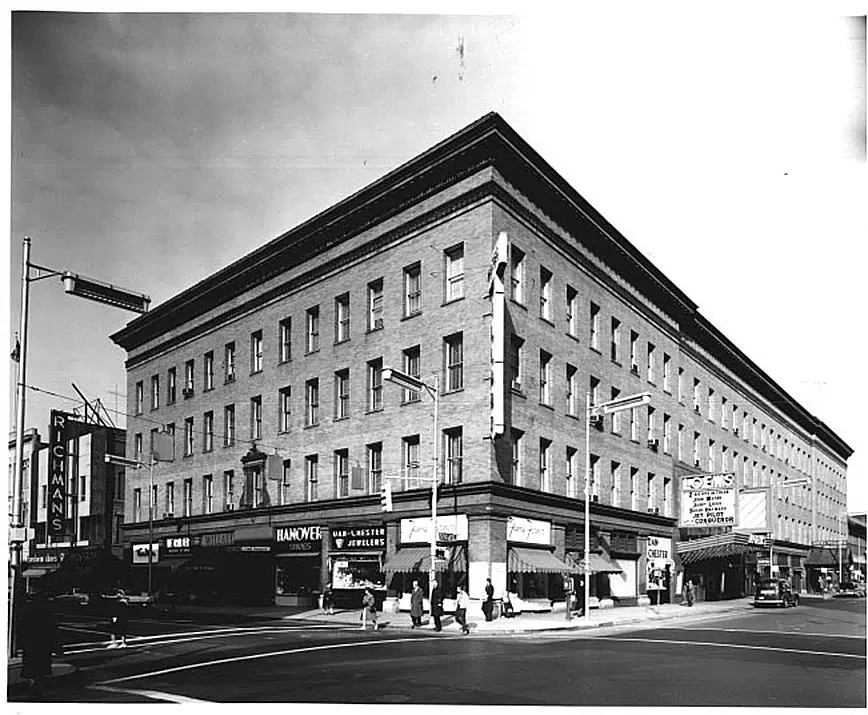

Exterior view by Milton Zink, 1957

Exterior view by Milton Zink, 1957

Ketcham named his new theater in honor of his father, Valentine Hicks Ketcham, son of a New York farmer who learned the trade of carpentry and ventured west in 1836 setting up a small store on St. Clair Street. His business slowly grew and by 1841 he had relocated to the better location of 32-34 Summit. But what really set him upon the path of financial success was marrying a woman whose father was the former mayor and owner of the largest dry goods business in the county. With the opening of the Miami and Erie Canal his wholesale business boomed and within in another five years Ketcham had sold the business and embarked on the more lucrative area of banking (Ketcham, Berdan & Co.). During the Civil War Ketcham's bank took over the First National Bank, with Ketcham himself assuming the presidency, and the carpenter's apprentice had climbed to the pinnacle of Toledo society. All during these decades Ketcham was shrewdly speculating in Toledo real estate at one time or another owning much of the present downtown. It is rumored Valentine may have won a large parcel of valuable land in a poker game held in Monroe, Michigan. (Blade, Oct. 3, 1999, p. 8). Whatever the truth may be, it is certain that upon his death in 1887, Valentine made each of his three children millionaires. (Harvey Scribner, Harvey Scribner, Memoirs of Lucas County and the City of Toledo (Madison, Wis., 1910), vol. 2, pp. 196-197, 390-392. (Madison, Wis., 1910), vol. 2, pp. 196-197, 390-392.)

Befitting a memorial to such a father, (and to his own social ambitions) George Ketcham was bold in the construction of his theater. He hired the city's most famous architect, Edward O. Fallis, the designer of the county courthouse who seems to have been given a very free hand. Fallis's designs included an unusual cantilevered balcony (one of the first of its kind in the United States). His floor plan broke with the common design of theatres of its day by arranging the theater's seats in straight rows rather than semicircular ones that accommodated more seats but gave some theatergoers obstructed lines of sight. To attract the highest quality entertainers, the basement was fitted with 18 elegant dressing rooms, each unusually supplied with hot water baths. And in an age when electric lights were still considered a luxury, the building was equipped with large dynamos in the basement sent direct current to 2400 incandescent lights. (Ohio Michigan Line, (Spring 1984), pp. 5-6)

Fallis and Ketcham, though bold in structural design were far more conventional in decoration. Befitting the Victorian era, the theater was awash in marble, velvet, and silk. A variety of Italianate sculptures and urns dotted the halls as did custom-made furniture in the French Empire, colonial, and Dutch styles. On either side of the proscenium were bas-relief cupids piercing a heart with the theater's signature "V" in its center. Still the building cost somewhere around $300,000, (around $6,000,000 in today's money).

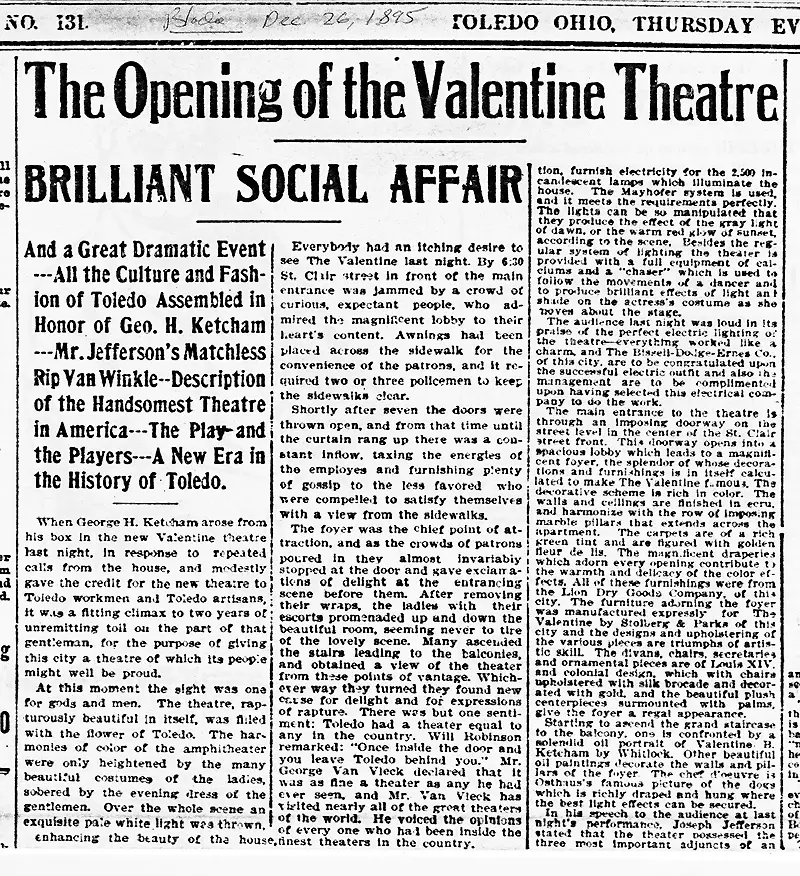

The Valentine Theater opened on Christmas night, 1895 and the demand for tickets was so great that they were auctioned off (Blade, December 26, 1895 [PDF]). Mr. Fred J. Reynolds bought the first box for the princely sum of $250, two-thirds of the annual income of the workers who cleaned the building. (Toledo Times, May 15, 1932) The first night's curtain went up on a production of Rip Van Winkle staring the veteran actor, Joseph Jefferson.

The Opening of the Valentine Theatre

The Opening of the Valentine Theatre

Ketcham had the misfortune of completing his building on the eve of the depression of the 1890s when property values stagnated and money was tight. Though Toledo kept more of an even keel than most cities in this period, it must still have been quite a windfall for Ketcham when the city council leased most of the building's second and third floors for city offices for $6,400. Ketcham was certainly grateful: after the first council meeting held in the new building, Ketcham invited all the politicos upstairs where the city engineer's offices had been turned into a lavish banquet room and the night was filled with "feasting and merry-making". One reporter noted that the "right royal night" made temporary friends of enemies, "Councilmen who seemed ready to fight while down on the floor below clinked glasses in good fellowship and never hesitated to tell each other what great men they were."

Thus did the Valentine Theater house the offices of Toledo's most famous politicians, Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones and Brand Whitlock, reformers who protested that the city's taxes were being drained away in the form of rent to one of the city's richest men. But neither Jones, nor Whitlock was ever able to convince a majority of the council to invest in a city hall and the Valentine Building would remain seat of the city's government until 1921 when rents that galloped past the $20,000 mark forced a hasty move to the newly completed safety building, a building intended to be the headquarters for the police and fire departments.(Blade, Jan. 17, 1954)

History was made at the Valentine on many occasions. It was there, in his campaign headquarters, that Jones watched the discouraging returns pour in from his failed 1899 race for the Governor's office. In 1903 hundreds of citizens crowded into the small council chambers and shouted down streetcar officials and won a municipally mandated fare reduction. The following year after Jones died, the council reversed their position and a famous citizens protest against high streetcar fares known as the 'petition in boots' (Brand Whitlock, Forty Years of It (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1914), pp. 176-180) paraded beneath the Valentine's windows. In the wake of the controversy Jones' Independent party elected three more aldermen and swept Brand Whitlock to an easy victory.

Toledo, being a central rail hub, was a convenient stop-over for acts on their way to Chicago or points further west. This along with the Valentine's luxurious reputation combined to bring all the greats to Toledo. Over the course of its first two decades, the Valentine Theater brought to Toledo a surprising array of theatrical and musical talent. Great orators graced the stage as well, including Mark Twain, the poet James Whitcomb Riley, and the great free thinker, Robert Ingersoll. By the early years of the twentieth century, the Valentine opened up its stage to less traditional acts. Harry Houdini played there in 1906 and an exhibition basketball game was held on its stage in 1912 (the underdog Toledo Overlands beat the Detroit Athletics, 47 to 37. (Blade, Jan. 13, 19, 1912).

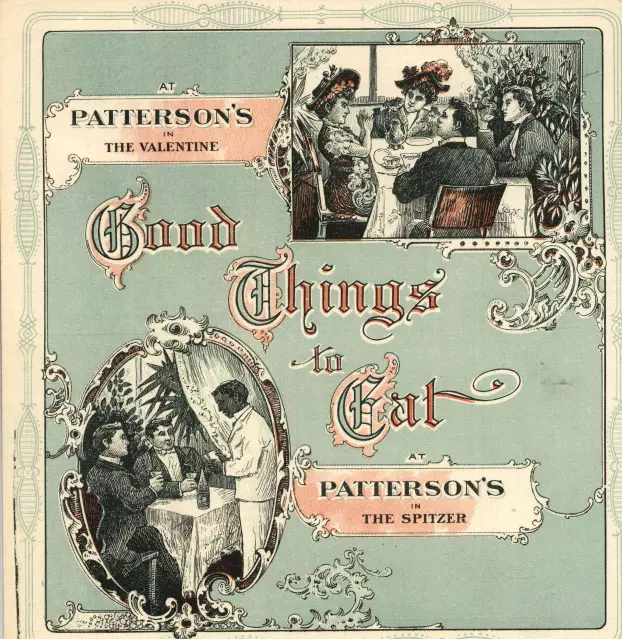

Advertisement for Valentine (formerly Patterson's) Cafe

Advertisement for Valentine (formerly Patterson's) Cafe

At its peak the Valentine was symbolized the golden age of Toledo. It housed one of the city's best restaurants, Patterson's (later known as the Valentine Cafe), a basement establishment that offered diners their choice of decors in private Dutch, Oriental, Venetian, Colonial, or German dining rooms. It was the 'society' place to go for squab en casserole, mutton chops, saute caribou, or filet mignon. In 1913, as the city boomed with the automobile and glass industries, a massive illuminated sign, 78 feet long and 68 feet high, bearing 7,000 lights and weighing 25 tons was hoisted into place on the roof of the Valentine. The animated sign could be seen for miles flashing its claim, "You Will Do Better in Toledo". (Blade, Dec. 17, 1913.)

In 1918 a screen was stretched across the stage and the Valentine doubled as a movie house. That thirty feet of sheeting signaled the end of the theatre's glory. With the depression came the demise of many touring companies and the public's escapist mania for the talkies. The Valentine's owners decided to concentrate on the movie end of the business and embarked on a $50,000 "renovation" that turned the grand opera house into a movie palace. (Blade March 13, 1932.) Most of the changes were cosmetic, except for the installation of a projection booth over the old balcony and the removal of the ticket booth from the lobby to the sidewalk. (Blade March 10, 1932. The biggest change was not inside but on the new electric sign - the old Valentine name was removed and that of a movie syndicate, "Loew's", was put up in lights.

By the 1960s, even the movie business was having trouble filling the thousand seats of Valentine and Loew's relocated its cinema to a smaller venue. Though a succession of other owners would try and make it go, the theater was finally bankrupt and shuttered in 1974. Two years later the city finally bought the building it had occupied as tenant so long before for $468,000, renaming it the Renaissance Building.

The hoped for renaissance was never happened and in August of 1983 a task force established by Mayor DeGood recommended the demolition of the Valentine as soon as possible, at a cost nearly equal to the original cost of building the building ($217,000 compared to $300,000). A campaign, spearheaded by the LCVHMS landmarks committee, architectural historian Ted Ligibel, theatre designer George Izenour, Richard Helldobler of the Toledo Ballet School, councilwoman Donna Owens, TMA curator Roger Mandle, James Hill of the University of Toledo's Theatre Department, and Rey Boezi of the Toledo Cultural Arts Center, and others, organized as the Friends of the Valentine, to save the theatre saved it from the wrecking ball. Within a month the council voted to save the theatre. (Ohio Michigan Line, (Spring 1984), p. 5; Blade, Oct. 3, 1999, p. 15.) Nearly twenty years later the dreams of these preservationists are coming true as the Valentine again prepares to open its doors after a $28 million dollar restoration.