Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Exhibit Gallery

African-American athletes in Toledo sport history

African-American athletes in Toledo sport history

From Moses Fleetwood and Welday Walker and the 1883 Toledo Blue Stockings, to the African American sparring partners who helped train Jack Dempsey for his crushing defeat of Jess Willard in 1919, to the various twentieth century football players at the University of Toledo and Toledo high schools, African Americans have played a large part in the athletic successes of Northwest Ohio.

This exhibit will highlight some of the great African American athletic pioneers from Northwest Ohio. This is just a small selection of the many athletes who shaped Toledo baseball in the early part of the twentieth century. Since the focus, as well as the mission, of Toledo’s Attic is on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this exhibit will not focus on modern players, such as the many current and future Detroit Tigers or past greats such as Kirby Puckett.

If you, the patrons of Toledo’s Attic, have any small histories of African American athletic pioneers, please feel free to email them to the content administrator. If you history is used online, it will include a reference to the submitter. Please include a list of the sources used for your history.

Baseball

Even as baseball began to follow the national trend towards racial segregation, Northwest Ohio was always home to more racial harmony in the sporting world. This section of the exhibit will highlight some of the great African American baseball players and teams throughout the early years of Toledo and Northwest Ohio baseball.

William Gatewood

William "Big Bill" Gatewood was a legend of the early years of the Negro Leagues, both as a player and as a manager. When he finally ended his career as both a pitcher and manager in 1928, Gatewood had played for some of the greatest Negro and Blackball franchises, as well as with players such as Cool Papa Bell, Rube Foster, and Satchel Paige.

"Big Bill" was actually quite big, 6'7” and 240 pounds to be exact. But for all his size, Gatewood was known more as finesse pitcher, although he was not afraid to knock down a player who was crowding the plate.

Gatewood’s stop in Toledo was far shorter than anyone had planned. Gatewood would not even manage the entire single season of the short-lived and under-financed franchise, with the last half of the 11-18 season managed by player-coach Candy Jim Taylor.

Gatewood is most widely known for how he changed two famous Negro League players. He is credited with changing Cool Papa Bell from a pitcher into an everyday switch-hitting outfielder, as well as teaching Satchel Paige his famous "hesitation pitch."

Sam Jethroe

Sam Jethroe was one of the many players who had a potential Hall of Fame Major League Baseball career shortened due to the color barrier. Jethroe, who was voted the oldest Major League Rookie of the Year when he won the award in 1950, starred at every level of baseball that he played.

Negro Leagues Career

Samuel "the Jet" Jethroe was born in East St. Louis, IL. in 1918. Like all the great African American players of the time, Jethroe's only option for playing professional baseball would be the Negro Leagues, and he joined the Cleveland Buckeyes in the early 1940s.

The great Buck O'Neil, who played against Jethroe while O'Neil was with the Kansas City Monarchs, stated that "the infield would have to come in a few steps or you could never throw him out."

Jethroe was an obvious talent, which his numbers would represent. During his six years with the Buckeyes, Jethroe would post a .342 batting average (.393 in 1946) and was selected to play in the prestigious East-West All Star game four times in his six-year Negro League career. After going hitless in his first couple of games, Jethroe showed his true talent in the 1947 East-West All Star games, going 4 for 8 with 2 triples, 2 stolen bases, and 5 RBI in the two games.

The 1947 East-West All Star Game series was especially important because it was attended by Major League baseball scouts looking for new talent after witnessing Jackie Robinson play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. And the scouts were able to see the best that the Negro Leagues had to offer, such as future Rookie of the Year Jethroe and Joe Black, Minnie Minoso, Don Bankhead, and Luis Tiant, Sr. (father of future star Luis Tiant). 1948 included such stars as Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Satchel Paige, and Minnie Minoso. Jethroe would also sign with a Major League club in 1948 – the Brooklyn Dodgers – and spent the 1949 season within the Dodgers minor league system.

The mass exodus of players after the 1947 game, coupled with bad business decisions and the growing pains (scalping, politics) of such an important game, would mark the last year that the East-West All Star game would outdraw the Major League All Star game. Although it would continue to be played until 1962, it would never again be as big as it was in 1947.

Jethroe and the Boston Red Sox

The question of why there weren’t any black players in Boston arose well before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. In the 1930s, Boston columnist Mabrey "Doc" Kountz began asking the team and the city as a whole this very question.

After years of Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey avoiding Kountz, Kountz thought his wish would finally be answered when Isadore Muchnick, a Jewish Boston City Council member armed with the renewal of a city-granted authority to violate the city's blue laws (professional sports on Sunday was prohibited), demanded an answer to this question from Yawkey and Braves President Bob Quinn. Muchnick stated:

“I cannot understand how baseball, which claims to be the national sport and which in my opinion receives special favors and dispensations from the Federal Government because of alleged moral value, can continue a pre–Civil War attitude toward American citizens because of the color of their skin."

Against the backdrop of a threat to require the two teams to observe the ban on Sunday baseball, three top Negro League players (Sam Jethroe, Marvin Williams, and Jackie Robinson) were brought in for what was thought to be an honest tryout for the Red Sox.

In April of 1945, the Red Sox put the three players through their paces, with Jethroe and Robinson routinely smashing balls off of Fenway Park’s famed Green Monster. In attendance for the tryout were Manager Joe Cronin, Field Coach Hugh Duffy, Pittsburgh Courier (historically black paper) writer Wendell Smith, and Mabrey Kountz. Tom Yawkey and Red Sox General Manager Eddie Collins, the player personnel decision makers, were not in attendance.

Even with Duffy's assessment that "they look good to me," none of the players were offered a contract by either of the Boston ball clubs. Branch Rickey, the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, would soon sign Robinson and later signed Jethroe in 1948. The Red Sox signed a Negro League player in 1953, a little-known infielder named Elijah Green – then proceeded to bury him in their minor league system (save for a one-night exhibition), along with newcomer Earl Wilson, in order to appease accusations that the Red Sox were racist.

Jethroe would continue to play for the Cleveland Buckeyes until 1948, when he was signed by Branch Rickey and the Brooklyn Dodgers for less than $10,000. After a short stay in the minor leagues, Jethroe was traded to the Boston Braves for two players and $150,000 in cash.

MLB Career

In a sign of things to come, Jethroe lit up the International League pitching while playing for Montreal, hitting .326; driving in 83 runs; and stealing 89 bases in 1949. Don Newcombe, a former Negro League star; NL Rookie of the Year; and teammate of Jethroe in Montreal, stated that Jethroe was the "fastest human being I have ever seen." Newcombe also played with Jackie Robinson and against Willie Mays.

Jethroe would finally start his Major League career in 1950, playing for the Boston Braves. He immediately showed the Braves the talent that had been hidden in the Negro Leagues for years, hitting .273 with 18 home runs, 58 RBI, and stealing 35 bases on his way to winning the National League Rookie of the Year Award in a landslide over second place finisher Bob Miller of the Philadelphia Athletics. Ironically, the American League Rookie of the Year that year – Red Sox player Walter "Moose" Dropo – also played in Boston. Jethroe remains the oldest player ever to be named Rookie of the Year, receiving the honor at the age of 32.

Jethroe would lead the league in steals in two of his three seasons with the Braves, amassing 35 in each of his first two seasons and 28 in his final year with the team.

Prior to the 1952 season, Jethroe was able to give the Red Sox a firsthand glimpse of what they had missed when he blasted a three-run home run over the Green Monster in a Braves-Red Sox exhibition game. However, it would be another 7 years before the Red Sox signed a black player.

Jethroe's Major League career in the Major Leagues was short lived due to his advanced age when he entered the league. By the end of the 1952 season, Jethroe's average plummeted to .232, he began to strike out more frequently, and his usually rock solid defense began to falter. Jethroe was released by the Braves at the end of the 1952 season and would only play one more professional season (1954) with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Toledo Mud Hens Career

Although he had been released from the Braves, Jethroe quickly caught on with the Toledo Mud Hens for the 1953 season.

Jethroe's time in Toledo would also be short lived, as he left to play for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1954. While with Toledo, Jethroe showed flashes of his old form, batting a .307 average. He also demonstrated his hitting power: in the long history of Swayne Field, Jethroe was the only player to hit a home run out of the stadium into the coal field outside of the left field wall, a hit which was measured at 472 feet.

Although he was not in Toledo for long, Jethroe left his mark on the team and the city. The 1953 team would be the last winning Mud Hens team before the franchise left for Kansas City in 1956.

End of Jethroe's Career and Post Baseball Life

Jethroe would have one more Major League at bat before being demoted to Montreal in the International League. The once dynamic hitter and base stealer was relegated to playing the part of a minor league journeyman, robbed of his chance at stardom due to the color line in Major League Baseball.

Jethroe would re-surface in Major League baseball in 1993 when several Negro League players, who at the time were still unrecognized by the Major League Hall of Fame, were given a short tribute prior to a Red Sox game. In 1997, Jethroe and former Negro League players sued Major League baseball in an attempt to be included in the Major League pension plan, which excluded most Negro League players who played less than four years of "professional baseball." Although the suit was dismissed, the players were finally given a pension by Major League Baseball. Jethroe died of a heart attack four years later in Erie, PA.

Although not recognized as one of the greats of Major League Baseball, Jethroe, along with Jackie Robinson and the other early pioneers who crossed the color line, helped pave the way for current Major League Baseball players. An obvious talent at all levels of the game, the only thing that stopped Jethroe from becoming a baseball immortal was the inherent racism in professional baseball that robbed him of the best years of his career.

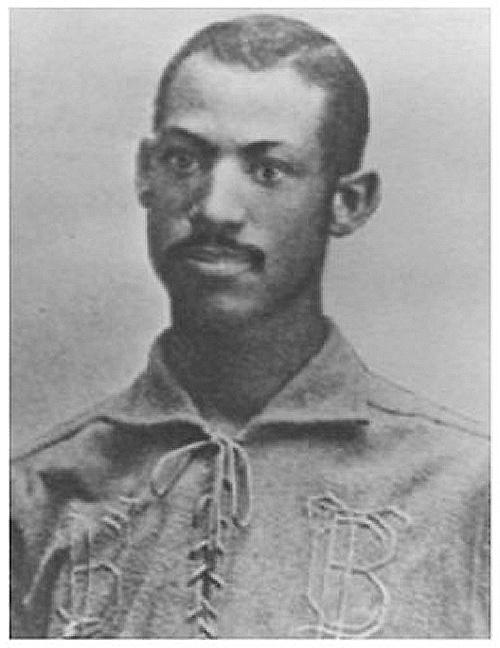

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker's promising but all too short professional baseball career mirrors the experience of most of the great African American ballplayers before the Negro Leagues began in the early twentieth century. Walker was a gifted defensive catcher and adequate offensive player, but his career would be cut short by racism. Walker, well educated for a man of any race in the late 19th century, respond to this racism first with ambivalence, then with anger, and finally with prose. His seminal work, “Our Home Colony,” put him directly in line with the thoughts and words of future leader Marcus Garvey in his call for a separation of the races and a return of African Americans to Africa.

Formative Years

Moses Fleetwood Walker was born in Mt. Pleasant, Ohio in 1857. Mt. Pleasant, which was only a few miles from the Ohio River border with slave state West Virginia (then still part of Virginia), was founded by Quakers from Pennsylvania and North Carolina and was an important stop on the Underground Railroad for escaped slaves as well as a source of Quaker abolitionist propaganda before and during the Civil War. Early in Moses's life, the Walker family relocated to Steubenville, Ohio, a town with most of the same morals and social ideals as Mt. Pleasant. It was this environment, along with the emphasis on education instilled in the Walker children by their physician/minister father and educated mother, that would be the backdrop of Moses Fleetwood Walker’s youth.

The Walker home was active during the Civil War. Although the elder Moses was too young to serve in the various "Colored" regiments of the Union Army, he did open up his home to persons fleeing oppression in the South, and even eventually took in two children born into slavery.

In what would prove to be a fortuitous move, the elder Walker made the trek to Oberlin, Ohio to help reform a congregation at a local church. The younger Moses would later follow his father to Oberlin, enrolling in the college preparatory academy and later Oberlin College.

College and Early Professional Baseball

Fleet began his studies at Oberlin College in 1878. At Oberlin, Walker studied the traditional college preparatory courses, excelling in his first year and maintaining satisfactory marks for the rest of his time there. It was also during this time that Walker would have the chance to study with and from such intellectuals as Mary Church Terrell, George Herbert Mead, Henry Churchill King, and Ida Gibbs Hunt. When the college removed its ban on competitive inter-collegiate athletics, Walker quickly joined the newly formed baseball team.

In a game against the University of Michigan, Walker showed the skills that would allow him to later play professional baseball. In Michigan’s 9-2 victory, Walker finished a triple short of the cycle, and quickly caught the eye of the Michigan coaches.

Walker, along with his pregnant girlfriend Bella Taylor, pitcher Arthur Packard (son of Union general Jasper Packard), and brother Welday soon left for Ann Arbor to play for the Wolverines. While at Michigan, Walker enrolled in the Law School, but never finished his degree.

Collegiate athletics were still in their infancy in the late 19th century; as there were few rules that required players to maintain their amateur status, players routinely made money playing for local traveling company teams. Walker was no different, and while at Michigan, he made extra money playing baseball for traveling company teams in the Midwest. One of the first teams that Walker played for was the Cleveland-based White Sewing Machine Company. It was during his experiences playing for this team against Louisville that Walker had his first on-field run-in with racism.

In Louisville to play against the local Eclipse ballclub, Walker saw discrimination and segregation firsthand. Although Jim Crow laws had not yet come into being, Black Laws ruled Southern cities, which kept alive the South’s desire to separate the races. Before the game began, Louisville players balked at playing in a game against a black player, a reaction that Walker would see often in his professional career. Walker's manager relented and Walker did not play in the game, even after the starting catcher went down with an injury.

After an excellent season for the University of Michigan and a brief season playing in New Castle, PA, Fleet and Welday set out to finish school and follow in the professional footsteps of their father. Welday looked to complete his degree in homeopathic medicine while Fleet worked on his degree in law, at one time taking a brief position with a Steubenville law firm.

1883 was supposed to bring Walker back to either Ann Arbor or New Castle. Much to the surprise of both towns, Walker ended up in a new place, once again playing baseball: Toledo, Ohio.

Professional Baseball Career

Walker began his organized professional baseball career with the Toledo Blue Stockings of the newly created Northwestern League in 1883. The team, which was owned and managed by Cleveland Plain Dealer sportswriter William Voltz, offered Walker the chance to again play with Harlan Burkett, a fellow classmate and teammate from Oberlin.

Although Burkett would prove to not be up to the task of professional ball, Fleet was thriving defensively (while only hitting .251) in his new surroundings. Voltz soon returned to writing and Charlie Morton took over as manager of the club, when was in fifth place at the time. Morton turned the team around, quickly securing the top spot in the league and finishing two games above the Saginaw franchise. The 1883 season finished with the Blue Stockings winning the Northwest League championship.

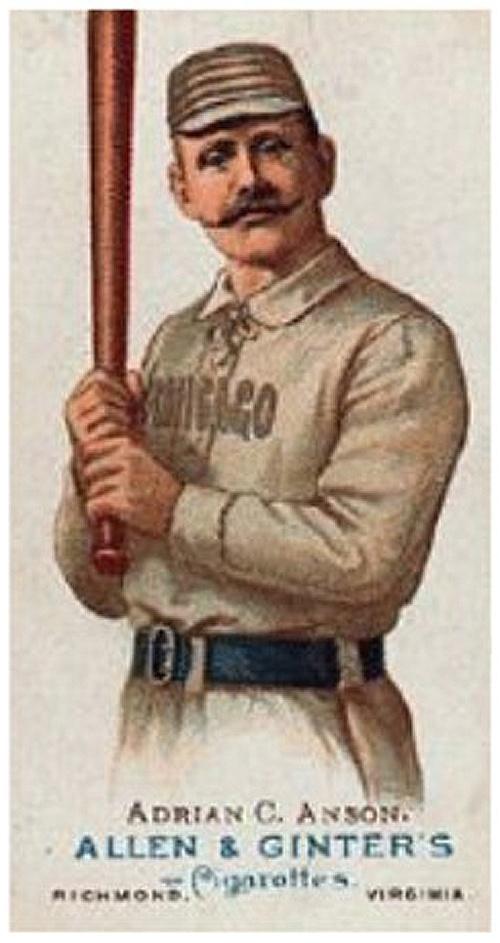

Life for Walker was about to get more complicated as the call to segregate baseball continued to gain traction. One of the major proponents of that idea was Cap Anson of the Chicago White Stockings.

Cap Anson Incident

After winning their first championship in 1883, the Blue Stockings were invited to play an exhibition game against the Chicago White Stockings. On August 10, the National League champs featured future Hall of Famer Cap Anson as a manager and player. At the time, Anson was in the prime of his career. Even though he had had an off season by his standards, he was still one of the most important figures in baseball.

When hearing that his White Stockings were scheduled to play against a team that featured an African American player, Anson (paraphrased to omit the racist language) stated that he would not set foot on the field if Walker played.

Although Walker was not scheduled to play his usual catcher position due to a hand injury (he did not use a glove), Toledo manager Charles Morton put Walker into the outfield after hearing Anson's racist comments. With the league's future still in economic limbo and fearing a loss of gate receipts, the Chicago ball club and Anson backed down and played the game anyway.

Although Morton forced Anson's hand and made him play against an African American player, Anson would have the final laugh, as he is considered by most to be a leading force in the gentleman's agreement that introduced the color barrier to baseball.

Last African American Until Jackie Robinson

After their 1883 championship campaign, Toledo was quickly invited to join the American Association, which, along with the National League, was the top level of professional baseball at the time. Walker and the Blue Stockings could not repeat their successes from 1883, with Walker hitting only .263 (an improvement) and doubling his error total in an injury-marred year that saw Toledo finish soundly in the cellar.

In addition to the injuries and poor play, Walker once again had to fight the scourge of racism on road trips to cities such as St. Louis; Richmond, VA.; and return trips to Louisville. Although some cities, such as Baltimore and Washington D.C., welcomed Walker, others did not. In one incident in Richmond, the Blue Stockings were advised not to play Walker because of a promise of "75 men sworn to mob Walker if he comes on the grounds."

Walker’s career in Toledo came to an end in 1885 and he left to join the Cleveland Western League franchise. Walker hit .275 that season (his best professional average) and continued to play his usual stellar defense. Walker ’s intellect was also put on display that season, as he was able to persuade his new team to fight the local "blue laws" that were threatening to bankrupt the team.

Unfortunately for Walker, baseball at this time was financially volatile, and the Western League quickly folded after the 1885 season. Fleet was able to play for ball clubs in Waterbury, Ct. in 1886 and later in Newark in 1887. In 1887, Walker would catch George Stovey, an African American pitcher, on his way to a league record 35-win season, while hitting .264 himself and still playing stellar defense.

1887 would not, however, end positively for Walker, as he again crossed paths with Cap Anson. Charles Hackett, the manager of the Newark club, stood his ground as Morton had in 1883, but this time, Anson and his team refused to play. Sadly, July 14, 1887 – the day the game was scheduled to be played – was also the same day that all new African American players were banned from International League play. This was not a popular decision in Newark and the surrounding area, where Walker had become a fan favorite. The Newark Daily Journal concluded that " Walker is mentally and morally the equal of any director who voted for the resolution."

Walker would finish out his career in Syracuse, once again encountering Anson in an exhibition game. This time, Walker was banned from playing. Although he played two more years in various independent leagues, by the end of the 1889 season, there was not a single African American player in professional baseball.

Moses Fleetwood Walker after Baseball

It has been rumored that Walker gave baseball two more years of his life, trying to play for independent teams in Terre Haute, IN and Oconto, WI, although no box scores or evidence can be found to prove this.

In 1891, Walker returned to Syracuse. One evening in April of 1891, while coming home from a local saloon, he was attacked by a group of white males. Walker killed one of the men in self defense. He was defended by the local sportswriters, as well as former legal mentor A.C. Lewis of Steubenville. Walker was acquitted on the grounds of self defense, but not without a stern warning from the judge to curb his growing reliance on alcohol.

The fortunes of the Walker family would only continue to get worse as Fleet moved back to Steubenville in late 1891 and resumed his work with the postal service. Just two weeks after the acquittal, Walker's father passed away in Detroit, where he had been living after separating from Carolina Walker. 18 months later, Caroline Walker passed away as well, only to be followed 18 months after her death by Fleet's wife, Bella Walker. In the span of three years, Walker had lost both of his parents and become a widower with three children. Three years later, he married Ednah Mason, whom he had met at Oberlin. But their honeymoon was short-lived, as Walker once again found himself in trouble with the law. This time he was found guilty of stealing mail and was sentenced to one year in prison. He made numerous appeals for his freedom, with one appeal going as far as the office of President William McKinley.

After the failure of the appeals and his release from prison, Fleet joined his brother Welday in his various ventures, which included running a hotel and a theatre and acting as an editor of The Equator, a weekly magazine on African American issues. It would be this activism in The Equator, coupled with the years of suffering due to racism, which would lead to Walker's most lasting achievement.

Walker's Literary Career

Fleet drew upon his education at various times while dealing with the racism and early Jim Crow that he repeatedly encountered. But at no time did the classical education that Moses and Caroline Walker desired for their children come to the forefront more than in the weekly journal The Equator and Fleet's pro-“Back to Africa” essay “Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America.”

The Equator, according to Welday, only lasted a short period of time, but it had a profound effect on Fleet. Unfortunately, no copies are known to exist. The journal would be a stepping stone to a far larger project: an eloquent plea for African Americans in America to return to Africa and settle in Liberia.

The theories found in “Our Home Colony” can be traced back to those of Bishop Henry McNeal Turner and his speeches and writings on the topic of African emigration. Turner would use his position in the African American political sphere to try and further the Back to Africa movement, at one point even convincing Southern politicians, some of whom had checkered racial pasts, to help gain government support for the movement. Walker was also learned on the other black leaders of the time, such as Booker T. Washington and W.E.B. Dubois, who is referenced in the essay on various occasions.

An excellent synopsis of the main thesis of “Our Home Colony” has been provided by Scott M. Walter. Walter believed that although Fleet quoted DuBois' famous dictum "the problem of the Twentieth Century is the color line," Walker put forth a solution far different than DuBois' assimilation theories. Walker advocated the emigration of African Americans to Liberia, a country that had been created by the US on the Western coast of Africa. This policy would be less eloquently championed by Marcus Garvey less than a decade later.

Unfortunately, Moses and Welday never made it to Africa (some say they never even tried) and the movement never truly gained any footing, even during the time of Marcus Garvey.

Fleet spent the rest of his life running the Cadiz Opera House with his wife Ednah, who passed away in May of 1920. During this time, Walker still had to deal with the obvious racism in society, both through the segregationist policies that forced blacks to sit in the balconies of his theatre and in the minstrel shows and racist motion pictures of the times (such as Birth of a Nation).

Walker did live to hear of the great victories of boxer Jack Johnson over the legion of "great white hopes," but was unable to show the footage of them in his theatre due to a ban on interstate traffic of fight films (brought upon by a fear of a black uprising due to viewing Johnson's victories) after the Johnson-Jeffries fight in 1910.

In July of 1920, Walker, drawing on his mechanical engineering roots from Oberlin, was able to patent and sell an improved film reel that sped up the reel changing process in theatres.

Walker would spend the final months of his life traveling in New York, eventually returning to Ohio and settling in Cleveland, where he re-entered the theatre business, only to leave the business for good three months later. Although not much is known about the last two years of Walker's life, it is known that he passed away on May 11, 1924 of lobar pneumonia. Walker's body was buried next to Bella, and later his children and Welday, in what was an unmarked grave. In 1990, after a search for new members for their hall of fame, Walker 's beloved Oberlin purchased a tombstone for his grave, with the ceremony highlighted by a speech given by his grandnephew, who still resided in Steubenville.

Boxing

Jack Dempsey

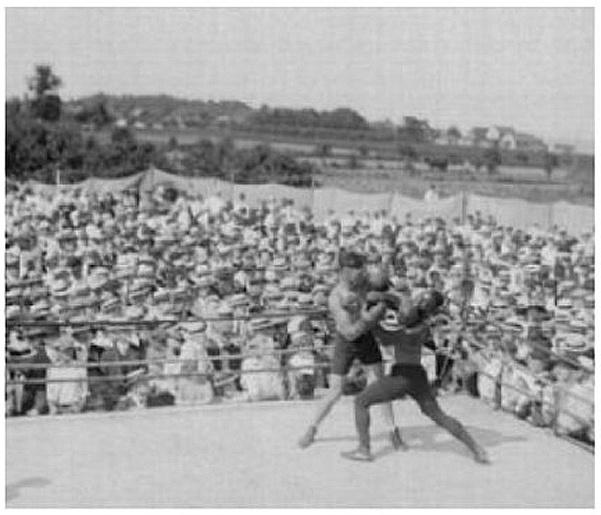

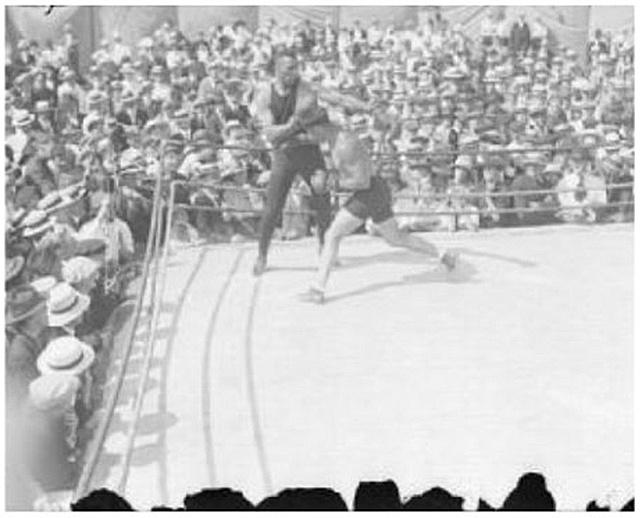

Any sports historian or boxing fan can tell you that this historic title fight (left) pitting the recently crowned Jess Willard, the last of the" great white hopes" who had won the Heavyweight Title from Jack Johnson four years earlier, and up and comer Jack Dempsey did not include any African American fighters. A simple picture can prove that fact.

The African Americans in this story come in through the various sparring partners that Dempsey fought prior to the match. This is particularly important to note since it was after the July 4, 1919 fight in Toledo that Jack Dempsey made his declaration to the New York Times that he would no longer face black opponents. Jack Dempsey's "color line" would have a long lasting impact on the sport, curtailing the growth of great African American fighters who would normally have had a shot at the championship.

Although none of these sparring partners went on to achieve accolades on the order of Jack Dempsey, all of them were quality fighters in their own right. Here are some of the fighters that Dempsey would spar with before his crushing defeat of Jess Willard in Toledo in 1919.

Jamaica Kid

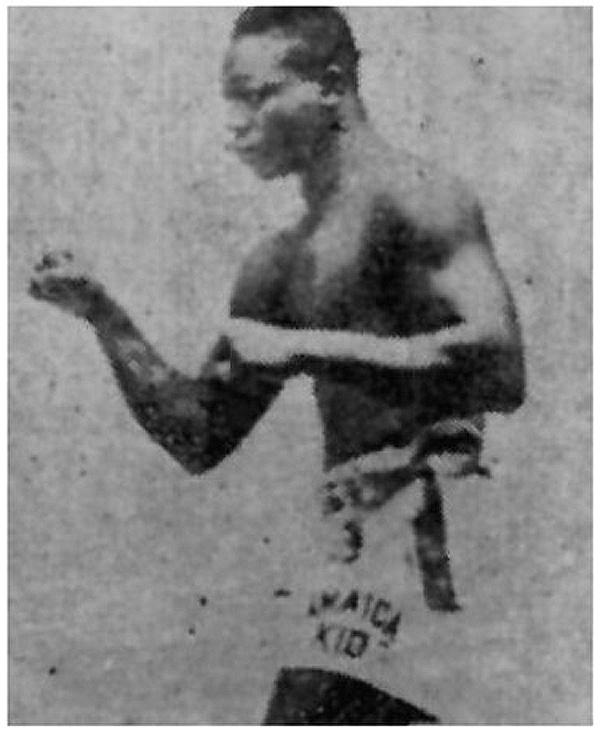

Jamaica Kid, Robert Buckley (Bulkey)

Jamaica Kid, Robert Buckley (Bulkey)

Not much is known of Dempsey sparring partner the Jamaica Kid, including his date of birth or where he was born. Even his name, which is thought to be either Robert Buckley or Robert Bulkey, is unknown.

Jamaica Kid, who is believed to have been born in Belize, was a popular sparring partner during his career because of his speed, and would work with Dempsey during his preparations for various fights, culminating with the July 1919 bout with Willard in Toledo. At this point in his career, which was roughly 25 bouts, Jamaica Kid had amassed only three wins. The inability to win would follow him for the rest of his career, a career in which he compiled an 18 and 60 record, with 9 draws.

Perhaps it was the proclivity for losing that allowed Jamaica Kid the chance to fight against many of the great boxers of his era, including Jack Thompson and Sam Langford.

As he had begun his life, the death of Jamaica Kid is also a mystery. It is known that he died in June of 1938 in New York, but the exact date is thought to be either June 12 or June 15.

William Tate

William "Big Bill" Tate was one of Jack Dempsey's favorite sparring partners during his rise to the Heavyweight title. Prior to the Willard fight in Toledo, Dempsey sparred with Tate numerous times, knocking Tate out on multiple occasions. Tate would prove to be a valuable asset to the up-and-coming fighter Dempsey (who was a 5-4 underdog in the fight), as he was able to prepare for the bout with someone roughly Willard's size.

Tate was more than just a sparring partner, amassing a nearly two decade fighting career. During his long tenure in the ring, the Alabama native would fight such legendary fighters as Sam Langford (a fighter that has been called one of the greatest "pounder for-pound" fighters ever), Harry Wills (who beat Tate on three occasions and was denied a shot at the Heavyweight Title by Dempsey's "Color Line"), Joe Jeanette, George Godfrey, and Jack Thompson.

Dempsey on Wills and Racism in Boxing

In his biography Dempsey offers up various reasons why the fight between himself and Wills never occurred. Most of them center upon his management.

Dempsey states in his biography that he actually had looked forward to fighting Wills, boasting that he had always been able to "lick those big slow guys" (Wills was 6'4", Dempsey was 6'1"). This could be seen as a true statement because Dempsey routinely scheduled larger sparring partners, such as Big Bill Tate, and savagely beat them in practice. Some of Dempsey's more decisive victories early in his career were also against large opponents, such as Jess Willard.

Another reason why Dempsey may have avoided a fight against a hungry fighter such as Wills would be his attitude at the time the fight would have occurred. By the mid 1920s, Dempsey had become accustomed to living the life of a roaring 20s star and saw boxing as a necessary evil that was required to continue his lifestyle. Prior to winning the title, Dempsey would fight monthly, sometimes even weekly. But upon winning the title, Dempsey began to take longer breaks between fights, with fight scheduled more than a year apart, and he commanded higher cuts of the gate to fight. Fighting a young, far hungrier fighter, one who may not have commanded such a large gate cut and would have brought along such external baggage, would not have made sense to a fighter at this stage of his career.

Dempsey states that another reason why the two never fought was due to contractual issues with his soon-to-have-been-former manager, Jack Kearns, as well as racial issues with promoter Tex Rickard. At various points in the process of securing the fight, issues of how much Dempsey would be paid for the fight were discussed; at one point, Wills was even given a $50,000 non-refundable down payment for the fight. Various offers were put forth for Dempsey (as much as $1 million), but the final numbers could not be worked out and the fight fell through.

The final issue, according to Dempsey, was that Rickard was still trying to live down "criticism for putting on the Johnson-Jeffries fight," as well as being accused of "humiliating the white race" by allowing such a fight to happen. The "great white hope" phenomena that grew out of hatred for Jack Johnson holding the most important of the boxing titles (others had been held by African Americans with no issue) was just one of the mentalities that arose from this time period. Once a Caucasian finally took the title back, promoters such as Rickard were not going to make the same mistake twice.

The final reason that Dempsey offers up is the fear of what could arise if such a fight did occur. One would just need to look at the bedlam that ensued after the Johnson-Jeffries bout, in which it is estimated that more than 26 people lost their lives in the post-fight celebration. With a champion as popular as Dempsey, some members of the New York Athletic Commission feared a repeat of the riot, "no matter who won."

In the end, Dempsey stated that he believed that "Wills had been gypped out of his crack at the title because people with a lot of money...thought that a fight against me, if it went wrong, would kill the business." (excerpts are from Dempsey: By the Man Himself)

Race in Heavyweight Boxing

"(I) was with Burns all the way. He was a white man and so am I. Naturally I wanted to see the white man win. Put the case to Johnson and ask him if he were the spectator at a fight between a white man and a black man which he would like to see win. Johnson's black skin will dictate a desire parallel to the one dictated by my white skin. . . . But one thing remains. Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the smile from Johnson's face. 'Jeff, it's up to you'" (Jack London, New York Herald, 12/27/1908, on the need for a white Heavyweight champion)

Throughout the early days of boxing, there was a clear demarcation of the color line and the inferences of Plessy v. Ferguson (separate but equal). Excluding infrequent instances of racial tensions, the races intermingled and fought against each other in the lower weight categories of boxing. Boxers such as bantam/flyweight champion George Dixon were able to regularly secure bouts against white opponents. Promoters sought out inter-racial fights in the lower weight classifications, usually due to the larger crowds that these fights would produce. But inter-racial fights did not usually find their way into the Heavyweight division, which, from the time of the last "London rules" (bare-knuckle) boxer John L. Sullivan, mostly adhered to the unofficial color line in boxing.

"I will not fight a Negro. I never have and I never shall." (Sullivan, in response to a fight against Peter Jackson).

During the reign of Sullivan, there were competent black fighters, such as Peter Jackson, who should have challenged for the crown. Only a small minority of upper-level white fighters, such as Jim Corbett, Jem Smith, and a young Jim Jeffries (future champion) agreed to fight black fighters, but none who held the crown would dare fight young black fighters such as Jack Johnson or later Joe Jeanette. Some speculate this was out of racism, some state it was out of fear of black fighters, and still others state it was out of a desire to avoid racially charged riots after fights. Whatever the cause, a black champion would not be crowned again until Joe Louis won the championship in 1937. During that time period, scores of great fighters would languish behind the color line, unable to truly showcase their skills.

Basketball

Although Toledo had professional basketball for less than a decade, the area still was able to make its mark on the integration of the game.

Toledo Professional Basketball

James Naismith, the creator of modern basketball, brought the game to Toledo at the turn of the twentieth century. Naismith, who invented the game at the Springfield, MA YMCA as a bridge sport between football and baseball seasons, introduced Carl Meissner and Howard Green to the game while they were working at the Toledo YMCA. Green and Meissner quickly introduced the members of the local YMCA to the sport and the game began to grown in Toledo.

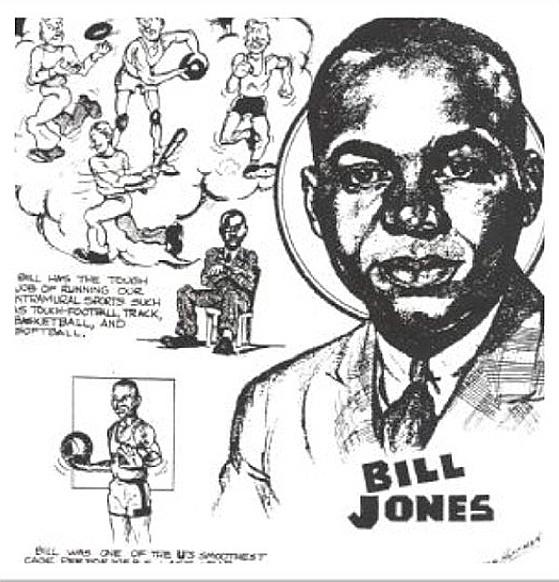

African Americans were able to play basketball in Toledo in the high school system. It was through this system that the players that made up one of the earliest Toledo basketball franchises, the Ciralsky Packers (teams were commonly named after the sponsors), came into being. The team would play against white teams in the city, as well as barnstorm across the United States. Led by players such as Bill Jones (first black professional basketball player), Link Smith (player and coach), Randolph Smith, and Herb "Shine" Taylor, they played white and black teams alike. The team was so successful they even defeated the professional New York Celtics, 30-27, in 1934.

Since the YMCA, like most American institutions, was segregated, an all-black YMCA was built in 1931. This new institution, like the segregated YMCA did for the white community, helped grow the game in Toledo’s African American community. The game would continue to grow at the University of Toledo as well, under the tutelage of Harold "Andy" Anderson.

In the 1940s, Toledo fielded its first professional team, the Jim White Chevrolets. The team suffered through a painful first season, finishing with a 3-21 record. 1941-1942 resulted in the drafting of many of the team’s players for military service – including star Chuck Chuckovits – and the team quickly turned to African American players from the area. Along with the Chicago Studebakers, the Toledo franchise was one of the first to integrate. Players such as Bill Jones, Casey Jones, Al Price, and Shannie Barnett all played for the Toledo club during this second season.

The war, coupled with the lack of popularity of the sport, led to the demise of the team after the 1942-1943 season. Although a few other teams were created, professional basketball in Toledo would never muster enough support to survive.

William Jones

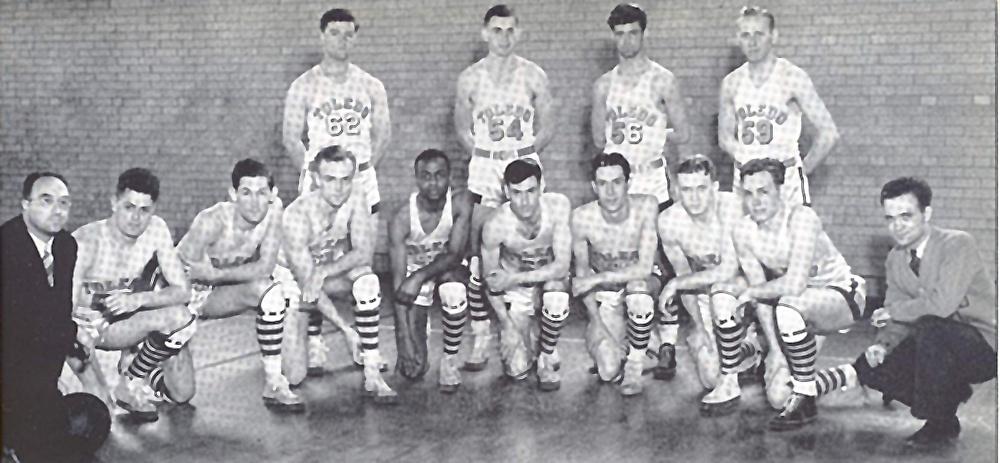

William Jones and his teammates, 1938

William Jones and his teammates, 1938

William Jones was one of the first great basketball players from Toledo. Jones led his Woodward high school basketball team to back- to-back Toledo city championships in 1928-1929 and 1929-1930, as well as leading his local YMCA team to various championships and undefeated seasons. Jones would continue his career at the University of Toledo, leading the team in scoring during the 1933-1934 season and starring with All-American Chuck Chuckovits on the 1936-1937 and 1937-1938 University of Toledo basketball teams, both of which finished ranked in the National Top 20.

Jones would continue to play basketball, this time with various barnstorming teams such as the Toledo White Huts (after the hamburger franchise), Joe's Toledoans, Ciralsky Packers, and the Harlem Globetrotters. In the 1942-1943 season, Jones, along with three other teammates and six players from the Chicago Studebakers of the NBL, officially integrated the sport (in 1950, Earl Lloyd became the first black NBA player). This occasion was not as momentous as Jackie Robinson four seasons later due to the lack of popularity of the new sport, coupled with the ever-increasing role of the United States in World War II.

Jones would play just one season with the Jim White Chevrolets of the NBL, with the team compiling a losing record that season and quickly disbanding the following season when Chuck Chuckovits did not return from the war.

Jones would continue to be a pioneer after his short basketball career ended. After relocating to the Los Angeles area, Jones, through the Los Angeles Urban League, was able to help secure employment for the first minority in 1946. Jones would continue to be associated with basketball, playing and owning various traveling teams, refereeing local Los Angeles games, and giving free coaching clinics throughout his life.

In 1991, Jones was inducted into the University of Toledo Athletic Hall of Fame for his exploits on the hardwood for the Rockets. He would live out the remaining years of his life in Los Angeles, passing away on May 7, 2006.

Football

During the last century, Toledo was home to two Professional Football Hall of Fame players and an undefeated college quarterback. All three of these players were African Americans, who while fighting racism, would become innovators in professional football.

Chuck Ealey

Chuck Ealey did not lose a football game from 1965 through 1971, a span of 65 games at Notre Dame High School and the University of Toledo. Even with this record of success, Ealey was not recruited outside of Ohio (only Miami University and the University of Toledo offered him scholarships) and lightly recruited by the NFL as a running back (which steered away from black quarterbacks).

Not desiring to move from the position that he excelled at, Ealey chose to ply his trade in the Canadian Football League. He was drafted by the Hamilton RoughRiders, and quickly became part of something that he hadn't been a part of since before high school: losing. But this did not deter him and he picked up where he left off at Toledo, leading the RoughRiders to 11 straight wins, an 11-3 record, and a Grey Cup championship.

Ealey would never match the numbers that he put up in his first season, but he continued to play in the CFL for six more seasons, concluding his career in 1978 after suffering a collapsed lung while playing for Toronto. Ealey would retire having never been able to fulfill his dream of playing in the NFL.

In 2006, a movement began at the University of Toledo to get Ealey into the College Football Hall of Fame. The reason for his exclusion was not due to race or oversight, but because of the rules for election that called for the player to either be a First or Second Team All American by one of the major voting bodies while playing college football. The "Induct Chuck" movement, through the Chuck Ealey Foundation, is currently working to get the rules for admission changed so players such as Ealey can be admitted into the Hall of Fame.

Today, Ealey is a motivational speaker for Investors Group, based in Mississauga, Ontario, a suburb of Toronto. He currently lives in Brampton, Ontario.

Jim Parker

Jim Parker was born and raised in Macon, Georgia in 1934. Parker and his family later moved to Toledo, where he attended and played football for Scott High School. While at Scott, Parker was recruited by Woody Hayes and Ohio State, where he would go on to win the Outland Trophy (best lineman) in 1956. Parker anchored the Ohio State running game to a perfect season and a national championship in 1954, opening up holes for Heisman winner Howard Hopalong Cassady (Parker finished eighth in the voting). Parker also earned All American honors twice during his career with the Buckeyes.

Parker was be the first draft choice of the Baltimore Colts, where he spent most of his career protecting the great Johnny Unitas from various positions. Parker would earn All Pro accolades as both a left guard (1962-1965) and tackle (1958-1962), during his illustrious career.

Jim Parker was inducted in to the Professional Football Hall of Fame in 1973, his first year on the ballot. Parker would be the first full time offensive lineman to ever earn that honor. He died in 2005 at the age of 71. View the New York Times obituary here.

Emlen Tunnel

Emlen Tunnel was born in Bryn Mawr, Pennsylvania in 1925. Tunnel starred at Rador High School in Rador Township, PA and later moved on to the University of Toledo. While at UT, Tunnel broke his neck. Told that he would never play competitive athletics again, Tunnel nevertheless led the Rockets to the NIT finals in 1946. Due to his injury, Tunnel was not able to enlist for the Army or Navy service in World War II. He would, however, later be accepted into the Coast Guard.

After the war, Tunnel transferred to the University of Iowa, where his career took off. After the 1947 season, Tunnel left school and requested a tryout with the New York Giants.

Tunnel, the Giants’ first African American player, would go on to be an important part of Defensive Coordinator Tom Landry's "umbrella" defensive scheme that was utilized by the team, which employed six defensive backs. In the 1952 season, Tunnel had more yards returning interceptions and kick returns than the NFL rushing leader (924 to Dan Towler's 894).

In 14 seasons, Tunnel recorded 79 interceptions, a record that stood until Paul Krause of the Minnesota Vikings broke it in 1979. Tunnel played in nine Pro Bowls, made All-NFL six times, and was later voted the All-Time best Safety in 1969.

After his final year in Green Bay and his playing days had ended, Tunnel would later become the first African American Assistant Coach when he took the position with the Green Bay Packers and Vince Lombardi. He was inducted into the Professional Football Hall of Fame in 1967.

Bibliography

Baseball

Barney, Robert K. David E. Barney. "Get Those Niggers Off the Field: Racial Integration and the Real Curse in the History of the Boston Red Sox." NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture. Vol. 16, Issue 1. 2006. Pgs. 1-5.

Bell, James "Cool Papa." "How to Score From First on a Sacrifice." American Heritage. August 1970.

Chenier, Robert P. Moses Fleetwood Walker: Ohio's Own "Jackie Robinson." Northwest Ohio Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 1. Pgs. 34-49.

Goldstein, Richard. Sam Jethroe is Dead at 83: Was Oldest Rookie of the Year. New York Times Obituary Section. June 19, 2001. New York Times Article.

Heaphy, Leslie A. The Negro Leagues: 1869-1960. McFarland and Company. London. 2003.

Holway, John B. Blackball Stars: Negro League Pioneers. Meckler Books. Westport, CT. 1988.

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball's National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, NE. 2001.

Moffi, Larry and Jonathan Kronstadt. Crossing the Line: Black Major Leaguers, 1947-1959. University of Iowa Press. Iowa City, IA. 1994.

Peterson, Robert. Only the Ball was White: A History of Legendary Black Players and All-Black Professional Teams. Oxford University

Ribowsky, Mark. A Complete History of the Negro Leagues: 1884-1955. Birch Lane Press. New York. 1995.

Stout, Glenn. Tryout and Fallout: Race, Jackie Robinson, and the Red Sox. Massachusetts Historical Review. Vol. 6. 2004. P. 11-39.

Walter, Scott. Walking the Line: Moses Fleetwood Walker and Race in America. Thesis (M.A.)--Bowling Green State University, 1995.

Zang, David. Fleet Walker's Divided Heart. University of Nebraska Press. Lincoln, NE. 1995.

Online Resources

Archival material, including photographs, used courtesy of the Negro Leagues e-Museum.

BaseballReference.com. Accessed online at http://www.baseball-reference.com/

Basketball

Floyd, Barbara. Chewing Tobacco, Meat Packers, Hamburger Chains, and Automobile Dealerships: Early Professional Basketball in Toledo. Northwest Ohio Quarterly. Vol. 75, No. 1.

William Jones Papers, UM 90. The Ward M. Canaday Center for Special Collections. The University of Toledo.

Stark, Douglas. Paving the Way: A History of Integration of African Americans into Professional Basketball. Basketball Digest. Feb 2001.

Boxing

Burn, Ken. Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. PBS Documentary. 2005.

Considine, Bob and Bill Slocum. Dempsey By the Man Himself. Simon and Schuster. New York. 1960.

Fleisher, Nat. Jack Dempsey. Arlington House. New Rochelle, NY. 1972.

Roberts, James and Alexander G. Skutt. The Boxing Register: The International Boxing Hall of Fame Official Record Book. McBook Press. Ithaca, NY. 1997.