African-American athletes in Toledo sport history

African-American athletes in Toledo sport history

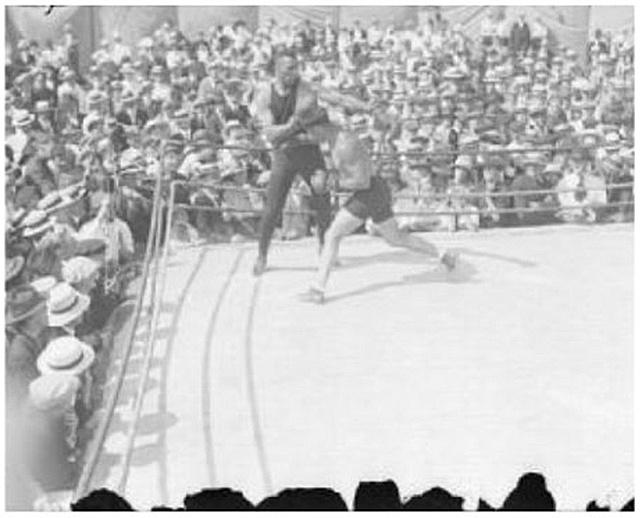

From Moses Fleetwood and Welday Walker and the 1883 Toledo Blue Stockings, to the African American sparring partners who helped train Jack Dempsey for his crushing defeat of Jess Willard in 1919, to the various twentieth century football players at the University of Toledo and Toledo high schools, African Americans have played a large part in the athletic successes of Northwest Ohio.

This exhibit will highlight some of the great African American athletic pioneers from Northwest Ohio. This is just a small selection of the many athletes who shaped Toledo baseball in the early part of the twentieth century. Since the focus, as well as the mission, of Toledo’s Attic is on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, this exhibit will not focus on modern players, such as the many current and future Detroit Tigers or past greats such as Kirby Puckett.

If you, the patrons of Toledo’s Attic, have any small histories of African American athletic pioneers, please feel free to email them to the content administrator. If you history is used online, it will include a reference to the submitter. Please include a list of the sources used for your history.

Baseball

Even as baseball began to follow the national trend towards racial segregation, Northwest Ohio was always home to more racial harmony in the sporting world. This section of the exhibit will highlight some of the great African American baseball players and teams throughout the early years of Toledo and Northwest Ohio baseball.

William Gatewood

William "Big Bill" Gatewood was a legend of the early years of the Negro Leagues, both as a player and as a manager. When he finally ended his career as both a pitcher and manager in 1928, Gatewood had played for some of the greatest Negro and Blackball franchises, as well as with players such as Cool Papa Bell, Rube Foster, and Satchel Paige.

"Big Bill" was actually quite big, 6'7” and 240 pounds to be exact. But for all his size, Gatewood was known more as finesse pitcher, although he was not afraid to knock down a player who was crowding the plate.

Gatewood’s stop in Toledo was far shorter than anyone had planned. Gatewood would not even manage the entire single season of the short-lived and under-financed franchise, with the last half of the 11-18 season managed by player-coach Candy Jim Taylor.

Gatewood is most widely known for how he changed two famous Negro League players. He is credited with changing Cool Papa Bell from a pitcher into an everyday switch-hitting outfielder, as well as teaching Satchel Paige his famous "hesitation pitch."

Sam Jethroe

Sam Jethroe was one of the many players who had a potential Hall of Fame Major League Baseball career shortened due to the color barrier. Jethroe, who was voted the oldest Major League Rookie of the Year when he won the award in 1950, starred at every level of baseball that he played.

Negro Leagues Career

Samuel "the Jet" Jethroe was born in East St. Louis, IL. in 1918. Like all the great African American players of the time, Jethroe's only option for playing professional baseball would be the Negro Leagues, and he joined the Cleveland Buckeyes in the early 1940s.

The great Buck O'Neil, who played against Jethroe while O'Neil was with the Kansas City Monarchs, stated that "the infield would have to come in a few steps or you could never throw him out."

Jethroe was an obvious talent, which his numbers would represent. During his six years with the Buckeyes, Jethroe would post a .342 batting average (.393 in 1946) and was selected to play in the prestigious East-West All Star game four times in his six-year Negro League career. After going hitless in his first couple of games, Jethroe showed his true talent in the 1947 East-West All Star games, going 4 for 8 with 2 triples, 2 stolen bases, and 5 RBI in the two games.

The 1947 East-West All Star Game series was especially important because it was attended by Major League baseball scouts looking for new talent after witnessing Jackie Robinson play for the Brooklyn Dodgers. And the scouts were able to see the best that the Negro Leagues had to offer, such as future Rookie of the Year Jethroe and Joe Black, Minnie Minoso, Don Bankhead, and Luis Tiant, Sr. (father of future star Luis Tiant). 1948 included such stars as Jackie Robinson, Larry Doby, Roy Campanella, Don Newcombe, Satchel Paige, and Minnie Minoso. Jethroe would also sign with a Major League club in 1948 – the Brooklyn Dodgers – and spent the 1949 season within the Dodgers minor league system.

The mass exodus of players after the 1947 game, coupled with bad business decisions and the growing pains (scalping, politics) of such an important game, would mark the last year that the East-West All Star game would outdraw the Major League All Star game. Although it would continue to be played until 1962, it would never again be as big as it was in 1947.

Jethroe and the Boston Red Sox

The question of why there weren’t any black players in Boston arose well before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. In the 1930s, Boston columnist Mabrey "Doc" Kountz began asking the team and the city as a whole this very question.

After years of Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey avoiding Kountz, Kountz thought his wish would finally be answered when Isadore Muchnick, a Jewish Boston City Council member armed with the renewal of a city-granted authority to violate the city's blue laws (professional sports on Sunday was prohibited), demanded an answer to this question from Yawkey and Braves President Bob Quinn. Muchnick stated:

“I cannot understand how baseball, which claims to be the national sport and which in my opinion receives special favors and dispensations from the Federal Government because of alleged moral value, can continue a pre–Civil War attitude toward American citizens because of the color of their skin."

Against the backdrop of a threat to require the two teams to observe the ban on Sunday baseball, three top Negro League players (Sam Jethroe, Marvin Williams, and Jackie Robinson) were brought in for what was thought to be an honest tryout for the Red Sox.

In April of 1945, the Red Sox put the three players through their paces, with Jethroe and Robinson routinely smashing balls off of Fenway Park’s famed Green Monster. In attendance for the tryout were Manager Joe Cronin, Field Coach Hugh Duffy, Pittsburgh Courier (historically black paper) writer Wendell Smith, and Mabrey Kountz. Tom Yawkey and Red Sox General Manager Eddie Collins, the player personnel decision makers, were not in attendance.

Even with Duffy's assessment that "they look good to me," none of the players were offered a contract by either of the Boston ball clubs. Branch Rickey, the General Manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, would soon sign Robinson and later signed Jethroe in 1948. The Red Sox signed a Negro League player in 1953, a little-known infielder named Elijah Green – then proceeded to bury him in their minor league system (save for a one-night exhibition), along with newcomer Earl Wilson, in order to appease accusations that the Red Sox were racist.

Jethroe would continue to play for the Cleveland Buckeyes until 1948, when he was signed by Branch Rickey and the Brooklyn Dodgers for less than $10,000. After a short stay in the minor leagues, Jethroe was traded to the Boston Braves for two players and $150,000 in cash.

MLB Career

In a sign of things to come, Jethroe lit up the International League pitching while playing for Montreal, hitting .326; driving in 83 runs; and stealing 89 bases in 1949. Don Newcombe, a former Negro League star; NL Rookie of the Year; and teammate of Jethroe in Montreal, stated that Jethroe was the "fastest human being I have ever seen." Newcombe also played with Jackie Robinson and against Willie Mays.

Jethroe would finally start his Major League career in 1950, playing for the Boston Braves. He immediately showed the Braves the talent that had been hidden in the Negro Leagues for years, hitting .273 with 18 home runs, 58 RBI, and stealing 35 bases on his way to winning the National League Rookie of the Year Award in a landslide over second place finisher Bob Miller of the Philadelphia Athletics. Ironically, the American League Rookie of the Year that year – Red Sox player Walter "Moose" Dropo – also played in Boston. Jethroe remains the oldest player ever to be named Rookie of the Year, receiving the honor at the age of 32.

Jethroe would lead the league in steals in two of his three seasons with the Braves, amassing 35 in each of his first two seasons and 28 in his final year with the team.

Prior to the 1952 season, Jethroe was able to give the Red Sox a firsthand glimpse of what they had missed when he blasted a three-run home run over the Green Monster in a Braves-Red Sox exhibition game. However, it would be another 7 years before the Red Sox signed a black player.

Jethroe's Major League career in the Major Leagues was short lived due to his advanced age when he entered the league. By the end of the 1952 season, Jethroe's average plummeted to .232, he began to strike out more frequently, and his usually rock solid defense began to falter. Jethroe was released by the Braves at the end of the 1952 season and would only play one more professional season (1954) with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Toledo Mud Hens Career

Although he had been released from the Braves, Jethroe quickly caught on with the Toledo Mud Hens for the 1953 season.

Jethroe's time in Toledo would also be short lived, as he left to play for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1954. While with Toledo, Jethroe showed flashes of his old form, batting a .307 average. He also demonstrated his hitting power: in the long history of Swayne Field, Jethroe was the only player to hit a home run out of the stadium into the coal field outside of the left field wall, a hit which was measured at 472 feet.

Although he was not in Toledo for long, Jethroe left his mark on the team and the city. The 1953 team would be the last winning Mud Hens team before the franchise left for Kansas City in 1956.

End of Jethroe's Career and Post Baseball Life

Jethroe would have one more Major League at bat before being demoted to Montreal in the International League. The once dynamic hitter and base stealer was relegated to playing the part of a minor league journeyman, robbed of his chance at stardom due to the color line in Major League Baseball.

Jethroe would re-surface in Major League baseball in 1993 when several Negro League players, who at the time were still unrecognized by the Major League Hall of Fame, were given a short tribute prior to a Red Sox game. In 1997, Jethroe and former Negro League players sued Major League baseball in an attempt to be included in the Major League pension plan, which excluded most Negro League players who played less than four years of "professional baseball." Although the suit was dismissed, the players were finally given a pension by Major League Baseball. Jethroe died of a heart attack four years later in Erie, PA.

Although not recognized as one of the greats of Major League Baseball, Jethroe, along with Jackie Robinson and the other early pioneers who crossed the color line, helped pave the way for current Major League Baseball players. An obvious talent at all levels of the game, the only thing that stopped Jethroe from becoming a baseball immortal was the inherent racism in professional baseball that robbed him of the best years of his career.