Boxing

Jack Dempsey

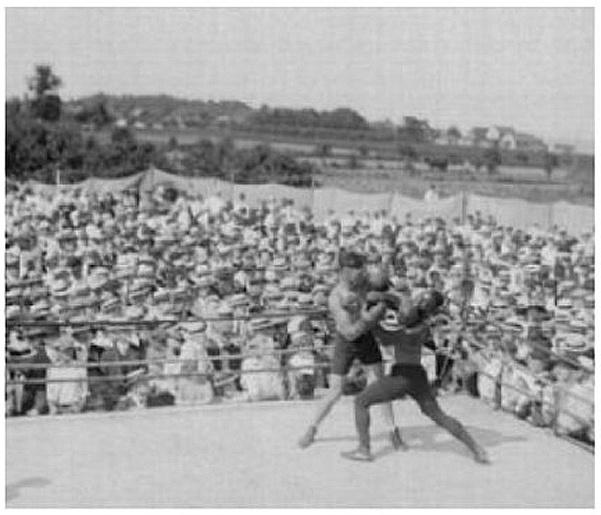

Any sports historian or boxing fan can tell you that this historic title fight (left) pitting the recently crowned Jess Willard, the last of the" great white hopes" who had won the Heavyweight Title from Jack Johnson four years earlier, and up and comer Jack Dempsey did not include any African American fighters. A simple picture can prove that fact.

The African Americans in this story come in through the various sparring partners that Dempsey fought prior to the match. This is particularly important to note since it was after the July 4, 1919 fight in Toledo that Jack Dempsey made his declaration to the New York Times that he would no longer face black opponents. Jack Dempsey's "color line" would have a long lasting impact on the sport, curtailing the growth of great African American fighters who would normally have had a shot at the championship.

Although none of these sparring partners went on to achieve accolades on the order of Jack Dempsey, all of them were quality fighters in their own right. Here are some of the fighters that Dempsey would spar with before his crushing defeat of Jess Willard in Toledo in 1919.

Jamaica Kid

Jamaica Kid, Robert Buckley (Bulkey)

Jamaica Kid, Robert Buckley (Bulkey)

Not much is known of Dempsey sparring partner the Jamaica Kid, including his date of birth or where he was born. Even his name, which is thought to be either Robert Buckley or Robert Bulkey, is unknown.

Jamaica Kid, who is believed to have been born in Belize, was a popular sparring partner during his career because of his speed, and would work with Dempsey during his preparations for various fights, culminating with the July 1919 bout with Willard in Toledo. At this point in his career, which was roughly 25 bouts, Jamaica Kid had amassed only three wins. The inability to win would follow him for the rest of his career, a career in which he compiled an 18 and 60 record, with 9 draws.

Perhaps it was the proclivity for losing that allowed Jamaica Kid the chance to fight against many of the great boxers of his era, including Jack Thompson and Sam Langford.

As he had begun his life, the death of Jamaica Kid is also a mystery. It is known that he died in June of 1938 in New York, but the exact date is thought to be either June 12 or June 15.

William Tate

William "Big Bill" Tate was one of Jack Dempsey's favorite sparring partners during his rise to the Heavyweight title. Prior to the Willard fight in Toledo, Dempsey sparred with Tate numerous times, knocking Tate out on multiple occasions. Tate would prove to be a valuable asset to the up-and-coming fighter Dempsey (who was a 5-4 underdog in the fight), as he was able to prepare for the bout with someone roughly Willard's size.

Tate was more than just a sparring partner, amassing a nearly two decade fighting career. During his long tenure in the ring, the Alabama native would fight such legendary fighters as Sam Langford (a fighter that has been called one of the greatest "pounder for-pound" fighters ever), Harry Wills (who beat Tate on three occasions and was denied a shot at the Heavyweight Title by Dempsey's "Color Line"), Joe Jeanette, George Godfrey, and Jack Thompson.

Dempsey on Wills and Racism in Boxing

In his biography Dempsey offers up various reasons why the fight between himself and Wills never occurred. Most of them center upon his management.

Dempsey states in his biography that he actually had looked forward to fighting Wills, boasting that he had always been able to "lick those big slow guys" (Wills was 6'4", Dempsey was 6'1"). This could be seen as a true statement because Dempsey routinely scheduled larger sparring partners, such as Big Bill Tate, and savagely beat them in practice. Some of Dempsey's more decisive victories early in his career were also against large opponents, such as Jess Willard.

Another reason why Dempsey may have avoided a fight against a hungry fighter such as Wills would be his attitude at the time the fight would have occurred. By the mid 1920s, Dempsey had become accustomed to living the life of a roaring 20s star and saw boxing as a necessary evil that was required to continue his lifestyle. Prior to winning the title, Dempsey would fight monthly, sometimes even weekly. But upon winning the title, Dempsey began to take longer breaks between fights, with fight scheduled more than a year apart, and he commanded higher cuts of the gate to fight. Fighting a young, far hungrier fighter, one who may not have commanded such a large gate cut and would have brought along such external baggage, would not have made sense to a fighter at this stage of his career.

Dempsey states that another reason why the two never fought was due to contractual issues with his soon-to-have-been-former manager, Jack Kearns, as well as racial issues with promoter Tex Rickard. At various points in the process of securing the fight, issues of how much Dempsey would be paid for the fight were discussed; at one point, Wills was even given a $50,000 non-refundable down payment for the fight. Various offers were put forth for Dempsey (as much as $1 million), but the final numbers could not be worked out and the fight fell through.

The final issue, according to Dempsey, was that Rickard was still trying to live down "criticism for putting on the Johnson-Jeffries fight," as well as being accused of "humiliating the white race" by allowing such a fight to happen. The "great white hope" phenomena that grew out of hatred for Jack Johnson holding the most important of the boxing titles (others had been held by African Americans with no issue) was just one of the mentalities that arose from this time period. Once a Caucasian finally took the title back, promoters such as Rickard were not going to make the same mistake twice.

The final reason that Dempsey offers up is the fear of what could arise if such a fight did occur. One would just need to look at the bedlam that ensued after the Johnson-Jeffries bout, in which it is estimated that more than 26 people lost their lives in the post-fight celebration. With a champion as popular as Dempsey, some members of the New York Athletic Commission feared a repeat of the riot, "no matter who won."

In the end, Dempsey stated that he believed that "Wills had been gypped out of his crack at the title because people with a lot of money...thought that a fight against me, if it went wrong, would kill the business." (excerpts are from Dempsey: By the Man Himself)

Race in Heavyweight Boxing

"(I) was with Burns all the way. He was a white man and so am I. Naturally I wanted to see the white man win. Put the case to Johnson and ask him if he were the spectator at a fight between a white man and a black man which he would like to see win. Johnson's black skin will dictate a desire parallel to the one dictated by my white skin. . . . But one thing remains. Jeffries must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the smile from Johnson's face. 'Jeff, it's up to you'" (Jack London, New York Herald, 12/27/1908, on the need for a white Heavyweight champion)

Throughout the early days of boxing, there was a clear demarcation of the color line and the inferences of Plessy v. Ferguson (separate but equal). Excluding infrequent instances of racial tensions, the races intermingled and fought against each other in the lower weight categories of boxing. Boxers such as bantam/flyweight champion George Dixon were able to regularly secure bouts against white opponents. Promoters sought out inter-racial fights in the lower weight classifications, usually due to the larger crowds that these fights would produce. But inter-racial fights did not usually find their way into the Heavyweight division, which, from the time of the last "London rules" (bare-knuckle) boxer John L. Sullivan, mostly adhered to the unofficial color line in boxing.

"I will not fight a Negro. I never have and I never shall." (Sullivan, in response to a fight against Peter Jackson).

During the reign of Sullivan, there were competent black fighters, such as Peter Jackson, who should have challenged for the crown. Only a small minority of upper-level white fighters, such as Jim Corbett, Jem Smith, and a young Jim Jeffries (future champion) agreed to fight black fighters, but none who held the crown would dare fight young black fighters such as Jack Johnson or later Joe Jeanette. Some speculate this was out of racism, some state it was out of fear of black fighters, and still others state it was out of a desire to avoid racially charged riots after fights. Whatever the cause, a black champion would not be crowned again until Joe Louis won the championship in 1937. During that time period, scores of great fighters would languish behind the color line, unable to truly showcase their skills.