The Toledo Mud Hens have had a long and storied history in Northwest Ohio. The club has pushed the color barrier when other teams were trying to exclude African American players, served as training grounds for future Hall of Fame players and managers, and has seen revitalization recently with two consecutive championship seasons.

This exhibit highlights the history of the Toledo franchise, from its humble beginnings as Toledo men's league team to its bright future in modern Fifth Third Field.

Toledo and the Negro Leagues

From Moses Fleetwood Walker to the Crawford and Cubs of the Negro Leagues, Toledo was a friend to African American baseball for nearly 60 years. This is the story of African American professional baseball in Toledo from 1883 until the “breaking” of the color barrier by Jackie Robinson in 1947.

In no way is this essay intended to be a definitive look at the long and storied history of the Negro Leagues in the United States. The focus is on the brief but rich history of African American baseball in Toledo, Ohio, with a brief background on the history of African American baseball in the United States. Excellent resources on the history of the Negro Leagues can be obtained by contacting the Negro League Baseball Museum.

Roots of the Negro League: Roots of Baseball and the Color Line

Baseball would follow the lead of boxing and other sports as beginning racially divided after the Civil War ended in 1865. Base ball (originally two words) had grown out of cricket and other sports in the mid nineteenth century, with its first recorded contest taking place in 1845. The first recorded African American game would be played 16 years later, when the Colored Union Club of New York lost to Weeksville (NY) 11-0. At this point, base ball was not a professional sport (the Reds of Cincinnati would be formed in 1869), with the teams and rules changing from game to game.

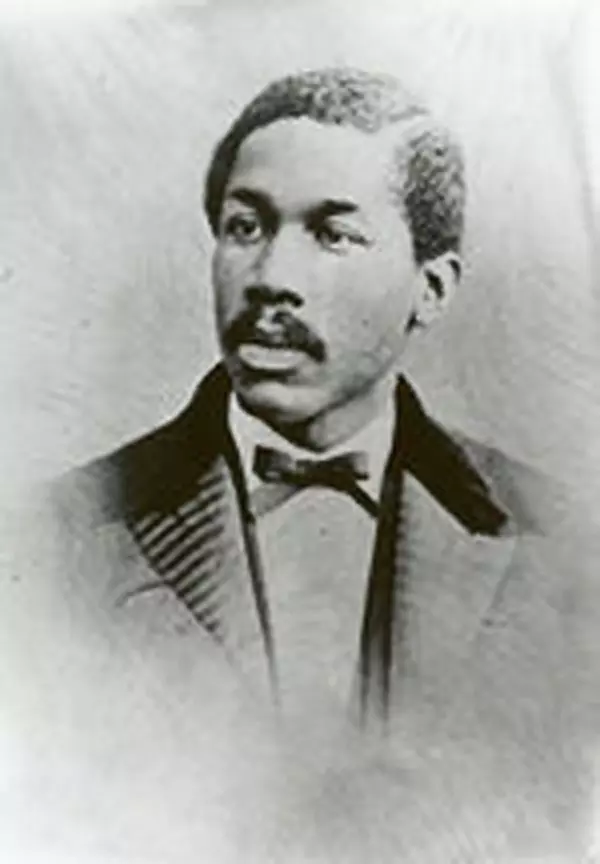

Even before the Reds became the first professional franchise in 1869, “blackball,” African American amateur leagues, was prevalent on the east coast. One of the major figures in black baseball was Octavius V. Catto, a retired Army major and teacher at the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia. Catto, a fiery speaker and champion of equal rights for African Americans, fought with the then-union of baseball, the National Association of Base Ball Players (NABBP), to include African American players in their ranks. Although the NABBP would later vote to not allow teams "which may be composed of one or more colored players" to play "organized" base ball, Catto, the owner of the Pythians, would continue to field his Philadelphia-based “blackball” team against any team that would play them, black or white.

After fighting the NABBP, Catto tried to use his increased political presence for a greater good and set his sights on equal voting rights for African Americans in 1871. This move would prove to be quite incendiary in Philadelphia, setting off riots throughout the city that prompted US Marine intervention to keep the peace. During this turmoil, Catto was accosted by a white male after leaving the Institute for Colored Youth and was shot and killed. The shooter was detained temporarily and then released and no charges were brought against him.

The 1871 murder of Catto not only ended the life of an early great civil rights activist, it also brought the "blackball" era to a halt. Passing away along with Catto and his beloved Pythians were the gains that Catto was able to make in securing African American equality in the new booming sport of base ball. The Pythians and other ballclubs lost direction and folded within a year of Catto's death, bringing to a close an early chapter in the development of the Negro Leagues.

From Catto to Fleetwood

Even though the murder of Catto brought the progression of African American baseball to a standstill, some players were still able to make a living playing the game. One player in particular was Bud Fowler.

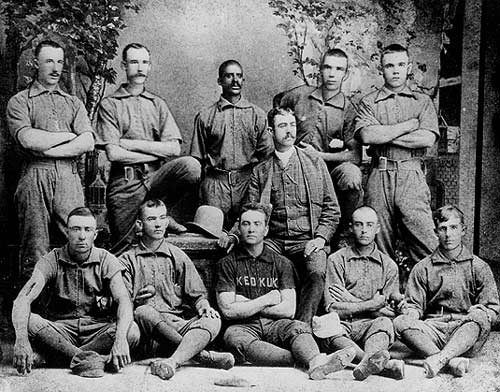

Born John W. Jackson, Fowler began his career as a pitcher in 1878, spending his brief pitching career with various teams throughout the Northeast. Fowler would later make his mark as a second baseman for the Keokuk, Iowa franchise of the Western League, playing several more seasons before the color line in baseball became more cemented. When Fowler's playing career began to wind down due to age and racial issues, he moved into organizing and managing African American teams, including the Page Fence Giants (Adrian, MI) of the Michigan League and the Cuban Giants in exhibitions against the professional Cincinnati Reds. Fowler would later manage other ballclubs such as the Smoky City Giants, the All-American Black Tourists, and the Kansas City Stars.

The first African American to play major league baseball was former Brown University student William Edward White, who played one game for the Providence Grays in 1879. White, who is also thought to be the first and only former slave to have played major league baseball, went 1-4 in his only game, making 12 put outs, scoring a run, and striking out once.

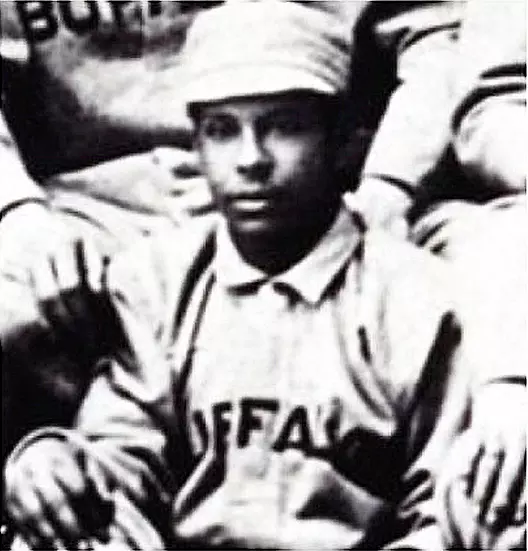

The man long thought to be the first African American player in the major leagues was Toledo Blue Stockings catcher Moses "Fleetwood" Walker. Fleet, as he was known, was a member of the Toledo franchise that spent a single year in the professional American Association. Although Fleet's play on the field was noteworthy, it was his dealings with Cap Anson, the future Chicago White Stocking Hall of Famer, that made him famous. Anson never forgot the 1884 incident in which he was rebuked when he attempted to get Walker off the field due to his race. When the two were scheduled to meet again on the field in 1887, this time with Walker playing for the Newark franchise. Fleet and George Stovey, the talented pitcher who holds the International League season win record with 35, once again drew the ire of Anson. This time, without Toledo and Charles Morton for protection, the International League, (led by the six teams that did not have black players), voted 6 to 4 to create an unofficial color barrier.

By the end of the 1889 season, the International League was an all Caucasian league, with Fleet Walker the last African American to play in the league. Stovey would later play in other minor league systems, as well as with the all-black Cuban Giants, but never would he make it to the major leagues. Walker would never play baseball again after the 1889 season, moving back to Steubenville to join his brother in several business ventures and to advocate a return to Africa for all blacks in the United States to end the racial divide.

Another great of the time relegated to the minor leagues due to the racist policies of the National League was Frank Grant. Grant, a second baseman for various franchises, was considered by most to be a Major League talent, but spent most of his career in the International League, eventually finishing with the Cuban Giants due to the new color barrier. Grant would eventually be voted into the Major League Hall of Fame for his talents in 2006.

By the end of the 19th century, blackball had returned, this time as more of traveling minstrel than baseball teams. Although teams such as the Page Fence Giants of Adrian, MI and the New Orleans Pinchbacks were filled with potential Major League talent ballplayers, they were forced to include gimmicks in their games – such as juggling or other routines – in order to entertain their fans. The gains made by serious professional ball players such as Bud Fowler, Fleet Walker, and Pythians owner Octavius Catto were put on hold until a new professional league could be created.

The Birth of the Negro Leagues

After another dozen years of constant barnstorming, talk of an all-African American league began to bubble to the surface again. With more and more southern African Americans moving to northern factory towns, a larger fan base emerged for the league.

The main benefactor of this new league would be former Cubans pitcher Andrew "Rube" Foster. Foster would later rise to prominence and fortune within the league, sometimes commanding 40% of the gate receipts for his teams’ barnstorming games.

During the first years of the 20th century, Foster was able to make the Leland Giants, the team formed from the Chicago Union Giants, into the best African American team. Well aware that most of the barnstorming teams were run and operated by rich white businessmen, Foster desired to have the operations turned over to blacks.

With the continued rise in the black population of the North, Foster, along with trusted white All Nations traveling team owner J.L. Wilkinson, set out to build a sustainable all-black baseball league. In 1920, with the First World War over, Foster got his wish and the Negro National League was formed in Kansas City. Although the league would never rise in prominence to compete with the major leagues, even folding briefly in 1933, the dream of Catto and Foster of an all-black professional baseball league had finally been realized.

Toledo Crawfords and Tigers

Toledo, Ohio had a brief history of involvement with the various incarnations of the Negro Leagues. All of the teams that played in Toledo were able to use Swayne Field, at the time one of the best facilities in all of the various minor leagues.

The first Negro League team to play in Toledo was the Toledo Tigers. The Tigers took the field for their one and only season in 1923, playing in Swayne Field with limited success. The team, made up of semi-pro players and remnants from the Cleveland Tate Stars, lasted most of the 1923 season, finishing with an 11-17 record. The team was disbanded in July of that season, with their players disbursed to the St. Louis Stars and Milwaukee Bears. The fans of the Tigers were treated to seeing Negro League great Bill Gatewood manage the first part of the season, with Candy Jim Taylor finishing the season as the skipper.

The African American community of Toledo would get another Negro League team in 1939, when the Crawfords arrived from Pittsburgh. The Crawfords, owned by Gus Greenlee, were unable to stay financially solvent and in 1939 were forced to leave Pittsburgh for Toledo.

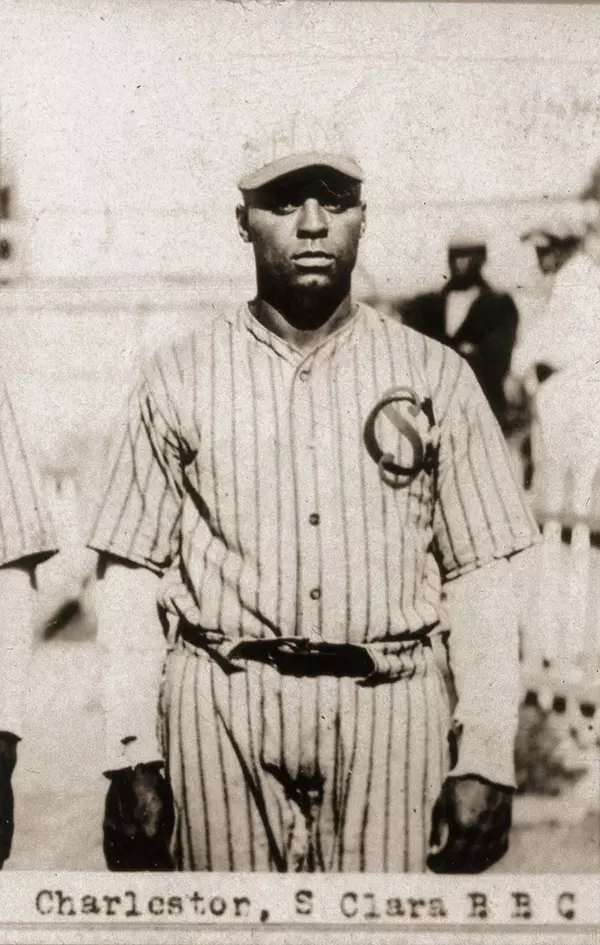

The Crawfords, named for a tavern in Pittsburgh, did not fare well in Toledo either, playing only 19 games at Swayne Field under the management of Oscar Charleston, who was also the first baseman. The highlight of the shortened season for the Toledo fans was witnessing Tommy Dukes, a well known journeyman player, hitting .385 for the transplanted Crawfords.

Unfortunately for Toledo, the team was still not financially viable and folded at the end of the 1939 season.

Turbulent Years, 1880-1900

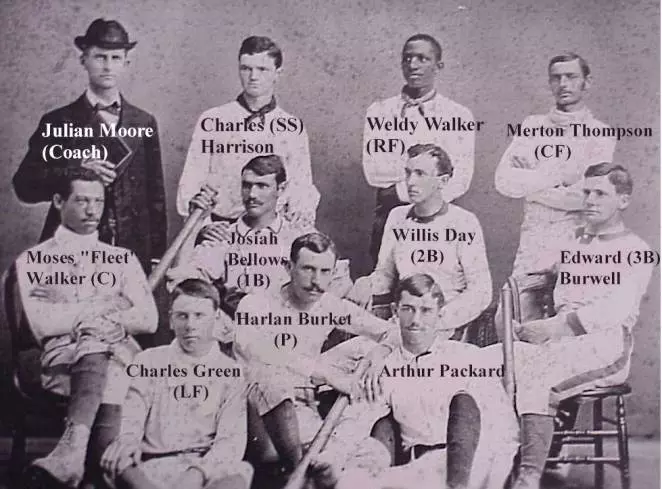

Team portrait at Oberlin College with Moses "Fleet" Walker

Team portrait at Oberlin College with Moses "Fleet" Walker

Base ball (originally two words) had already become well established in Northwest Ohio prior to the formation of the "professional" Toledo Base Ball Association in 1883. The league was made up of ten ball clubs and included Noah H. Swayne, a Toledo area businessman, in its ranks.

The rules of base ball in the 1880s were slightly different than the rules that we know today. Walks, which now come after the fourth non-strike, were allowed after seven. Overhand pitching was illegal and stolen bases were not allowed.

In the first years of Toledo professional base ball, the results were mixed. The first professional game played in the city was won by the Toledo Blue Stockings 5-4 over Bay City on May 5, 1883. The 1883 Blue Stockings would go on to win the Northwestern League pennant under manager Charles Morton.

Following the Cap Anson incident (see next section) at the end of the 1883 season, the Blue Stockings began play in 1884 in the American Association of the major leagues. Major League baseball was growing by leaps and bounds in the 1880s, with games being played in more than 30 cities in 1884 alone. This jump in competition proved to be too much for the newly named Toledos and they finished the season in eighth place, well out of the running for the pennant. Major League baseball’s run of good fortune ended and by the end of 1885, so had the run of Toledo baseball. The Toledos, now of the Western League, were contracted and baseball left Toledo for three years.

Baseball player and manager Charlie Morton returned to Toledo in 1889 with the Black Pirates of the International League. The Pirates played well enough in 1889 to secure an invite back to the American Association of the Major Leagues in 1890, finishing in a respectable fourth place and a couple games above .500 each season. But this would only last one season, as financial woes brought on by lagging ticket sales brought the Toledo franchise to contraction once again in 1890.

Baseball in Toledo refused to die in the 1890s, even in light of the Chicago World's Fair in 1892 and the stricter enforcement of Toledo’s "Blue Laws" forcing the team out of town or into bankruptcy twice in the decade. The 1896-1897 Swamp Angles/Mud Hens became a proven winner to close out the decade, taking the pennant in 1896 and 1897 and finishing no worse than third in from 1890-1900 under manager Charles Stroebel.

Notable players/opponents: Moses Fleetwood Walker, Cap Anson, Tony Mullane, Hank O'Day.