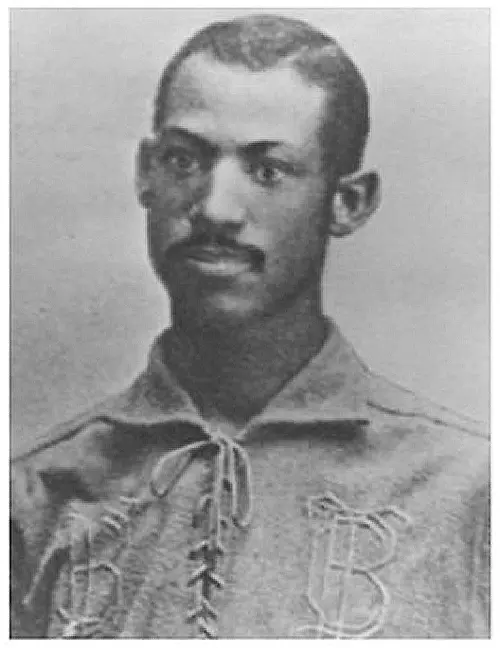

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker was born in Mt. Pleasant, Ohio in 1857, the fifth child of Caroline and Moses Walker. The family moved to Steubenville so that the elder Moses could begin practicing medicine. Fleet, as he was known to his family, and his brother Weldy would attend all black schools until the city high school was desegregated.

After graduating from Steubenville, Fleet would go on to Oberlin College, a school known for its progressive admission policies towards blacks and women. Fleet took up baseball at Oberlin, and his obsession with the sport nearly caused him to flunk out. After starring for the newly created Oberlin baseball team, Fleet, Weldy, and Fleet's pregnant future wife all left to enroll at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

After starring at Michigan and several stints with professional traveling teams, Walker joined the Toledo Blue Stockings and led them to the Northwestern League crown in his first season. Walker earned $2,000 for the 1883 season, a large sum for a player of any race at the time.

The end for Walker was near after the August incident with Cap Anson, one of many racist incidents that would follow Walker throughout his short career. Fleet, along with his brother Weldy, would play Major League baseball for one season with the new Toledo franchise, but the segregationist policies advocated by Anson derailed any advancement of Walker's career.

Walker would finish his minor league career with the Syracuse Stars in 1889. One evening, he was attacked by a group of white males. He was able to defend himself, killing one of the men in the process. After a long trial, Walker was found innocent and left New York to return to Ohio. Weldy, now a businessman back in Steubenville, invited his brother to come back to work with him. Weldy and Fleet would later run a movie theatre and hotel in Steubenville.

Outside of his business pursuits, Fleet also became a spokesman for Black Nationalism and Marcus Garvey. He wrote and published the Equator, a magazine on African American issues. In 1908, Walker published the pamphlet Our Home Colony: A Treatise on the Past, Present, and Future of the Negro Race in America, stating that "the only practical and permanent solution of the present and future race troubles in the United States is entire separation by emigration of the Negro from America."

Walker passed away in 1924 in Cleveland, Ohio.

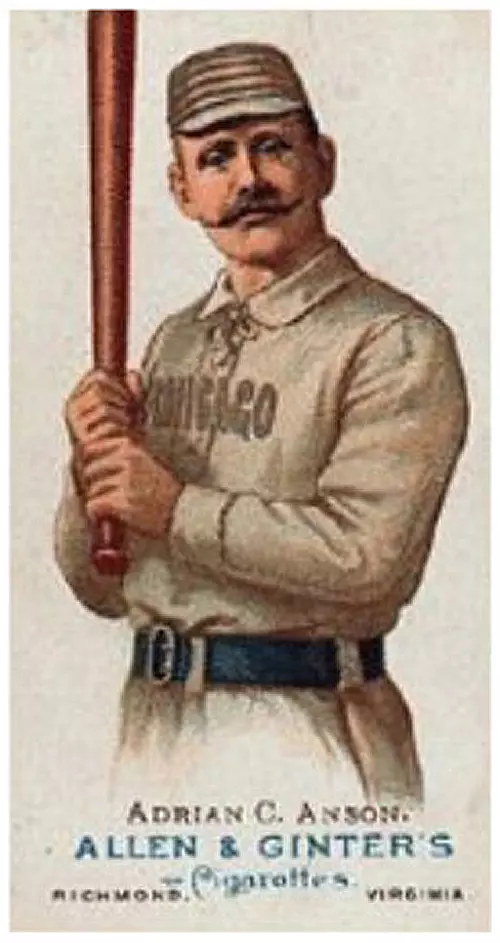

Cap Anson Incident

The 1883 championship season also brought with it a fair share of controversy. The star of the Blue Stockings, Moses Fleetwood Walker, and his brother Weldy were both African American baseball players at a time when the color line in baseball was just beginning to be drawn.

After winning their first championship in 1883, the Blue Stockings were invited to play an exhibition game against the Chicago White Stockings. On August 10, the National League champs featured future Hall of Famer Cap Anson as a manager and player. At the time, Anson was in the prime of his career. Even though he had had an off season by his standards, Anson was still one of the most important figures in baseball.

When hearing that his White Stockings were scheduled to play against a team that featured an African American player, Anson stated that he would not set foot on the field if the Walkers played.

Although Walker was not scheduled to play his usual catcher position due to a hand injury (he did not use a glove), Toledo manager Charles Morton put Walker in the outfield after hearing Anson's racist comments. With the league's future still in economic limbo and fearing a loss of the gate receipts, the Chicago ball club and Anson backed down and played the game.

Although Morton forced Anson's hand and made him play against an African American player, Anson would have the final laugh as he is considered by most to be a leading force in the gentlemen's agreement that introduced the color barrier to baseball. After the Walkers and a couple other players retired, the game of baseball stayed predominantly segregated until Jackie Robinson broke through in 1947.

Mud Hens, Iron Men, and Soumichers, 1902-1926

The dawn of the twentieth century found relative stability and prosperity in Toledo baseball. The Mud Hens finished a strong third in the Inter State League during the first season of the new century under manager Charles Stroebel. Even with the folding of the Inter State league in 1900, the Mud Hens continued to play on in a new league that rose from its ashes, the Western League. The Mud Hens would move to the American Association in 1902, staying in that league until the team left Toledo in 1955.

Armory Park: A photo of a baseball game being played at Armory Park, located off Spielbush Street in Toledo, Ohio.

Armory Park: A photo of a baseball game being played at Armory Park, located off Spielbush Street in Toledo, Ohio.

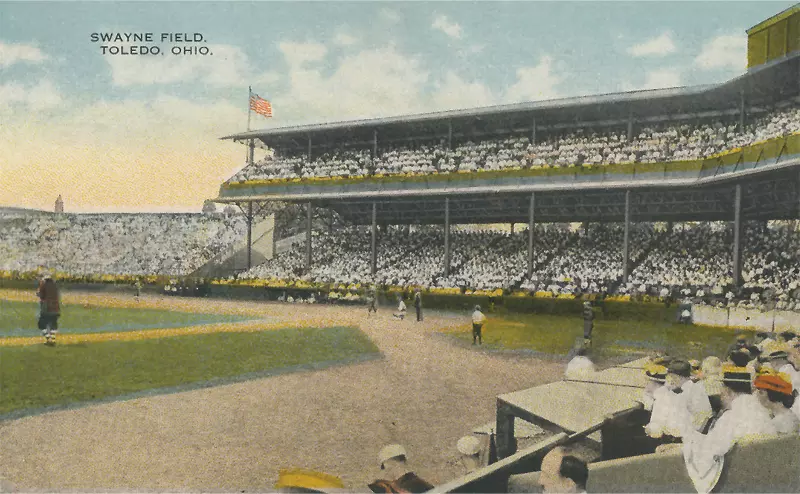

With the newfound stability of the American Association, it became obvious that Armory Park was no longer a suitable home for the franchise and that the team needed a modern stadium to play in. With this in mind, Swayne Field opened for play on July 3, 1909. The park, which was built on land donated by an old friend of Toledo baseball, Noah Swayne, was considered to be the "finest park in minor league baseball" at its opening. Toledo baseball would call Swayne Field home until 1955.

The Toledo franchise went through multiple owners during the early twentieth century. The first, J. Edward Grillo, a Cincinnati sports editor, tried to infuse the struggling franchise with a winning attitude. The franchise was able to rise out of the American Association cellar, even placing as high as fourth in 1906. The next owner was William R. Armour, the man credited with signing Ty Cobb in Detroit. Armour was able to turn around the struggling team in 1908, nearly taking the team to the American Association pennant. On the heels of this successful season, Armour, using land donated by Toledo businessman and former player Noah Swayne, built Swayne Field. Armour spared no expense in the construction of his state-of-the-art ballpark.

After the 1910 season, Armour sold the Mud Hens to Clevelander Charles Somers, who quickly moved the team to Cleveland in 1914 to block the expansion of the Federal League. The city of Toledo would be home to the South Michigan League Soumichers in 1914 and 1915, but low attendance due to the team’s poor play forced the Soumichers to play their home games on the road in 1915.

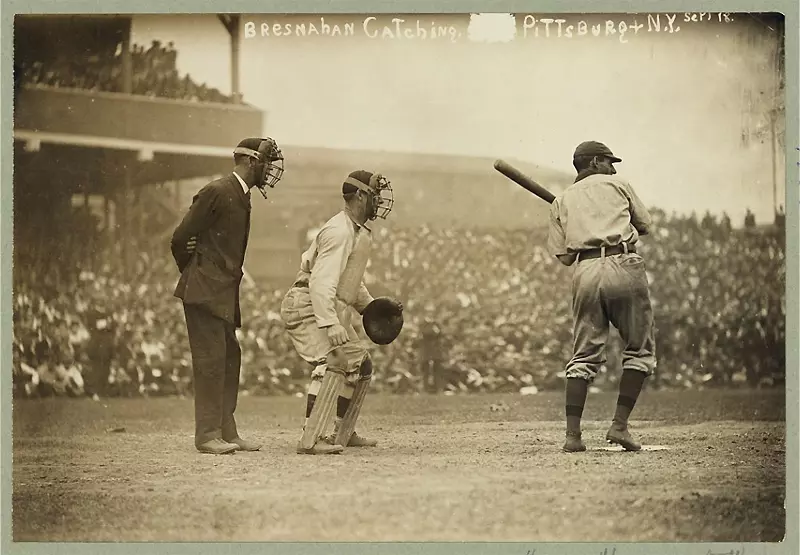

Roger Bresnahan, catching for the New York Giants

Roger Bresnahan, catching for the New York Giants

With the folding of the Federal League in 1915, professional baseball was brought back to Toledo by native son Roger Bresnahan. Bresnahan, who had left Toledo to become a Hall of Fame catcher for the New York Giants, retuned as owner; player; and manager of the newly named Iron Men. During Bresnahan's tenure the team improved instantly, winning 87 games in 1920 and barely missing the playoffs. This would be short-lived, as the team slipped back into its losing ways, finishing near last or last during the next five seasons. The team was still a decent draw due to the former and future Major Leaguers on the roster during this time, such as Jim Thorpe; James Middleton; Freddie Lindstrom; Hack Wilson; Dutch Schliebner; and Bill Lamar.

After 1902, the Toledo franchise suffered through two decades mostly of sub-.500 seasons, with the 1906; 1910; 1912; and 1920 seasons being the notable exceptions. All of this was soon to change with the return of Roger Bresnahan and the introduction of Casey Stengel as the new manager in 1926.

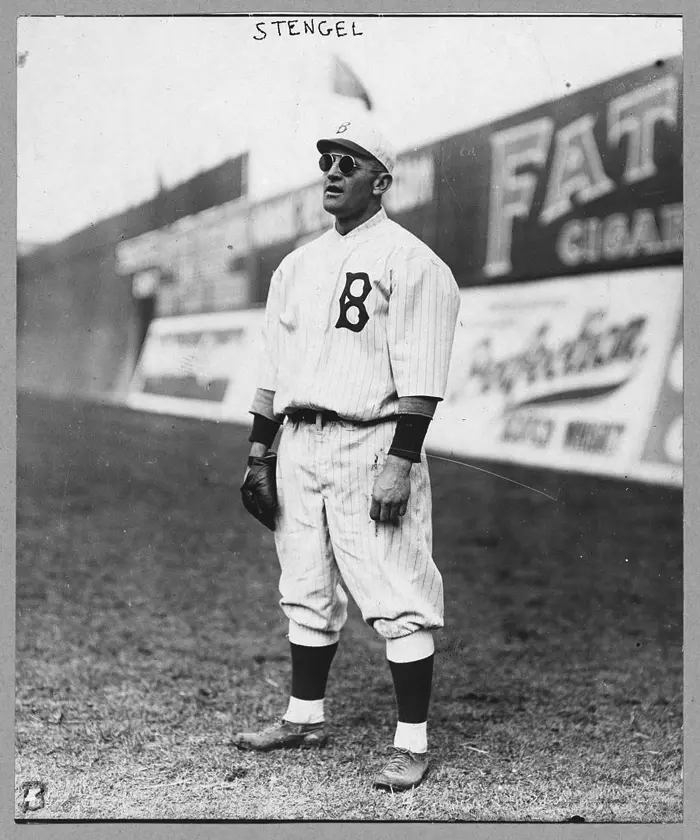

Casey Stengel, full-length portrait

Casey Stengel, full-length portrait

Champs to Chumps, 1928-1950

The 1927 team would prove to be the last championship Toledo team for more than half a century. The team would quickly be dismantled, with most of the major parts graduating to the Major Leagues in 1928 or 1929. After a second 100 loss season in 1931, Stengel left the Mud Hens to begin his Hall of Fame Major League manager career.

Toledo Manager Casey Stengel, (right), and Giants' Manager John McGraw (left), 1926

Toledo Manager Casey Stengel, (right), and Giants' Manager John McGraw (left), 1926

During the 1930s, the Mud Hens suffered through the Great Depression along with the rest of the country. At the beginning of the Depression, the team went into receivership in 1929, with local businessman Waldo Shank rescuing the team from contraction in 1929. Minor league baseball would have to turn to gimmicks, coupled with the excellent play on the field, to avoid economic extinction during the Depression.

The first gimmick was the introduction of night baseball. The idea was not a new concept, as the Negro League Kansas City Monarchs, in many ways pioneers of baseball, had been transporting portable lights during the various barnstorming tours of the United States. The Mud Hens would introduce night baseball to Toledo on June 23, 1933, defeating the Columbus Red Birds 2-1 behind the 15-strikeout performance of Monte Pearson in the inaugural night game. It would be almost two more years before the professional Cincinnati Reds would introduce lights to the Major Leagues.

Another gimmick, which has also worked more recently within all of the major professional sports, was the extension of the playoff season. Under the previous system, only the top two teams would make the playoffs to battle for the Junior World Series. Under the new Shaughnessy playoff system, four teams were now invited.

Another major innovation that was sweeping throughout minor league baseball was the institution of the "farm team" system. Toledo would have various Major League affiliates throughout the depression, beginning with the Indians in 1932 and also sending players to the Tigers and St. Louis Browns during the 1940s.

The 1930s and 1940s were not kind to the Mud Hens. After the surprising 1930 campaign, the team would finish under .500 in all but five seasons, finishing in last place most of those years. As could be expected, in the years when the team played poorly on the field, they also did poorly at the gate. This was evident in the 1936 and 1937 seasons. In 1936, the team finished a woeful 59-92 and drew nearly 70,000 fans. The next season, the team bounced back, finishing in second place and drawing almost 260,000.

The beginning of World War II brought a new role for baseball: morale booster. Even though Toledo and all of the other ball clubs lost players to the war effort (10 in both 1942 and 1943), baseball did continue. The teams put on the field by the Mud Hens did not fare particularly well, with only the playoff season (due to the Shaughnessy playoff system) of 1944, which was quickly followed up by sub-.500 seasons from 1945 to 1953. 1948 found the St. Louis Browns pulling their affiliation with the Mud Hens due to the team’s poor play. The Tigers would take over the minor league franchise the next season.

Notable Players: Ned Garver, Pete Gray, Sam Jethroe, Boris Martin, Monte Pearson, Hal Trosky