Acklin Plant Exterior, 1925

Acklin Plant Exterior, 1925

Exhibit Gallery

By Benjamin Grillot, 2000

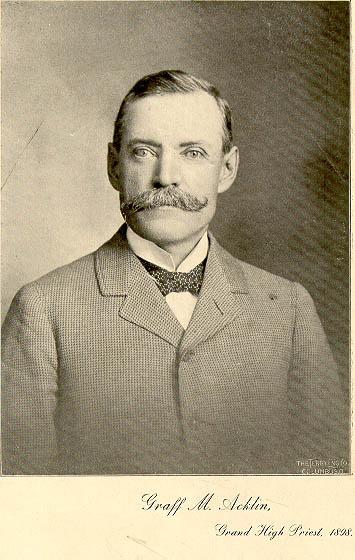

I. Early Days - "To such men as the late Grafton M. Acklin is the city of Toledo indebted for its prominence in the industrial world.." -The Story of the Maumee Valley, 1929.

A. Toledo, Ohio in 1911, A Backdrop

The story of Acklin Stamping, and really the story of Toledo's metal working industry, begins in 1911. The world was a radically different place in those days. Brand Whitlock, as Toledo's mayor, led a rapidly growing city of 170,000 people. The city and indeed the country were on the cusp of incredible technological change. In 1911, horses still dominated transportation and the speed limit was a mere 8 miles per hour. However this was all about to change in the next several years with the arrival of affordable automobiles, brought to the market by a number of companies including Toledo's own Willys-Overland Motor Company.

Acklin Stamping Plant, late 1930s

Acklin Stamping Plant, late 1930s

Throughout the city there was an overriding sense of optimism and hope for the future. Technological innovations were changing the fundamental ways people did things. However, the realities of industrial life were hard for working class men and women. The organization of major unions for unskilled workers had yet to take any effective steps towards improving worker safety or working conditions. A large number of immigrants were arriving in Toledo from around the world, primarily from Ireland and Eastern Europe.

The world was becoming a busy, noisy place. Industry was quickly making Toledo one of the most prominent and important cities in the Midwest. The Libbey Glass Company's arrival in Toledo from Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1888 had given Toledo a solid lead in the glass industry. Toledo was a prime location for industry because of its proximity to natural resources and key Midwestern markets like Chicago and Detroit. With the arrival of the Edward Ford Plate Glass Company (founded in 1898) and the Owens Bottle Machine Company (founded 1903), it soon became the center of the American glass industry. These companies revolutionized the glass industry by utilizing assembly line-style techniques of mass production.

Henry Ford, working outside of Detroit, pioneered techniques of mass production in the manufacturing of the automobile. This quickly emerging industry sixty miles north became increasingly important to Toledo at the turn of the century. Already a leader in the production of bicycles, Toledo firms utilized many of the same parts in the production of automobiles. The Lozier-Pope Company introduced its first steam-powered automobile -- "The Toledo" in 1900, but it was relatively lacking in both speed and power. The Pope Company's 1903 model, the "Pope-Toledo" was a more durable and popular automobile. Selling for about $3,000 (more than many people's annual salary), it was truly a luxury vehicle. In 1907, the Pope Company went bankrupt and remained in arrears for two years until it was purchased by John Willys in 1909. Willys paid off the debt and reorganized the company, forming the Willys-Overland Company, a firm that would later introduce the Jeep and the Wagoneer to the world.

An assembly line was used by Henry Ford in order to mass-produce perfectly identical automobiles in his Detroit plants. Each vehicle produced in this way was made up of thousands of pieces of steel, each precisely shaped, which were then assembled in factories. These pieces of metal were created at metal stamping plants, and as the automobile industry began to grow, so did the metal stamping industry.

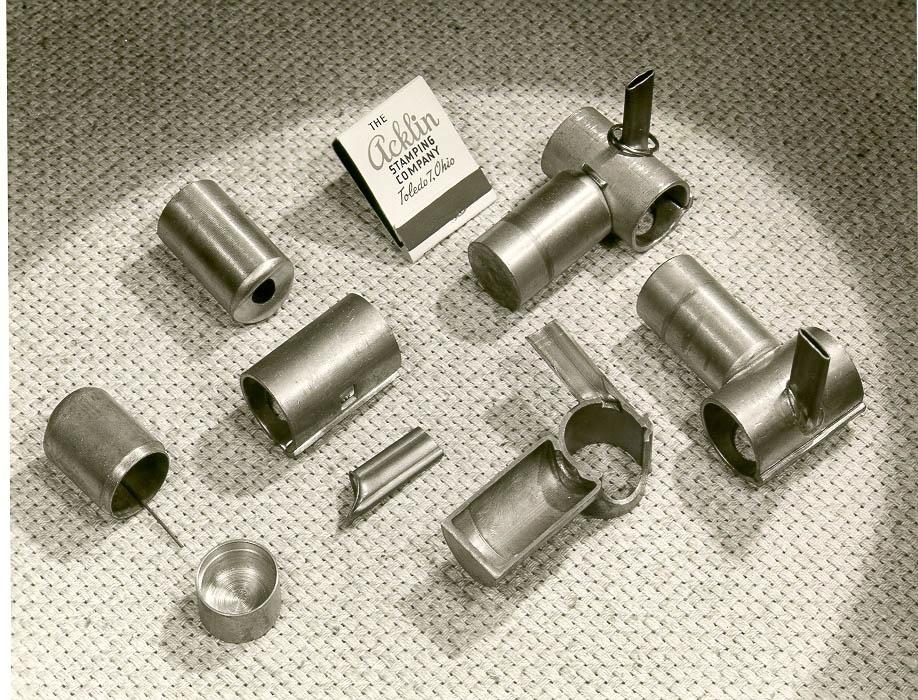

Metal stamping is essentially a means of shaping sheets of metal into the precise shapes required by a wide variety of industries. Steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, is rolled into flat sheets at a mill and then shipped to a metal stamping plant. That sheet of metal is placed into the bed of a press and a large, carefully shaped object called a die is then pushed under extremely high pressure onto the steel, forming it in some way. In order to create a finished, usable result from a sheet of raw steel, several different operations are performed on increasingly precise presses.

There were two methods in which a company could fill its demands for these stamped metal parts-- either through the creation of an in-house department which would supply the company's entire needs, or through out-sourcing the parts to various "jobbing" concerns. In the Toledo area, three metal stamping companies arose in 1911 alone to meet the growing need.

It is not surprising that in early 1911, when Grafton Acklin, nearing his 60th birthday, looked to the future, he decided to retire as President of the Toledo Machine and Tool Company and open, with three of his sons, the Acklin Stamping Company. But in order to understand Grafton Acklin's vision it is important to understand the man himself, and his career which led up to the formation of this company.

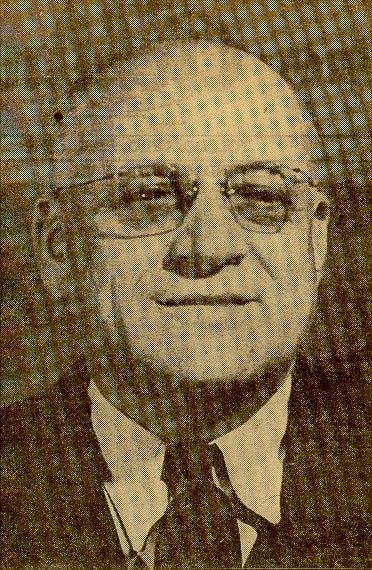

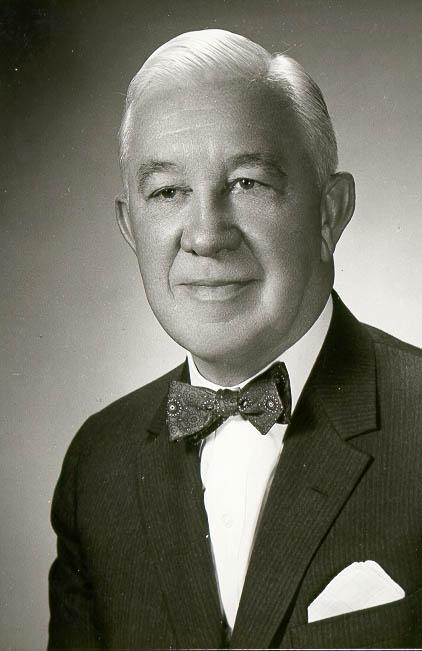

B. Grafton Acklin, Founder

Grafton Acklin, Acklin founder and president from 1911-1926. Photo from 1898.

Grafton Acklin, Acklin founder and president from 1911-1926. Photo from 1898.

Grafton Acklin was born on the banks of the Ohio River in Aberdeen, Ohio on the 30th of July, 1851. One of eight children, Grafton attended school in Aberdeen until the age of 15 when he moved, with his family, to Toledo. Mr. Acklin then began work in Toledo as a clerk in a wholesale grocery store, and after several years of hard work he became one of the owners. After some time, however, this partnership dissolved and Grafton and his partner, Samuel Wood, formed Acklin and Wood, a company supplying grocers with roast coffee and spices for wholesale.

By the late 1880s Grafton was considered one of the leaders of Toledo's business community. In 1896, the Toledo Tool and Machine Company asked Mr. Acklin to take over as the company's president. They hoped that his energy and vision would help the company achieve new levels of success.

The Toledo Machine and Tool Company had been founded in 1888 and specialized in the production of heavy metal working equipment -- presses, shears, and formers for the shaping of sheet iron. In 1897, the year following Grafton Acklin's appointment to Toledo Machine and Tool's helm, he expanded the company’s business overseas, supplying British bicycle firms with presses. In 1899 Toledo Machine and Tool introduced a special press for the making of gas stoves, and by 1900 had branched out into the making of planers, milling machines, boring mills, and cranes. Keeping up with technological innovations and the growing and changing nature of the industry, the company, under Grafton's leadership, continued to grow until it became one of the largest manufacturing and industrial concerns in Toledo.

By 1911, however, Grafton saw the emerging potential of the nascent automobile industry. He recognized that as mechanized production would grow there would be an ever increasing demand for stamped metal parts and that the potential for producing these parts would far outstrip the demand for the machines and presses to produce these parts. He was also nearing his 60th birthday and wanted to create a business with his three sons that would survive him.

C. The Family and the Founding

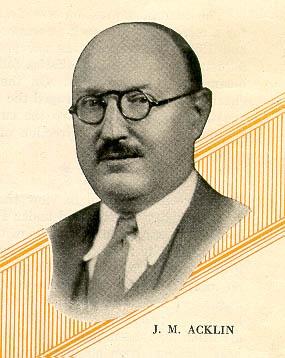

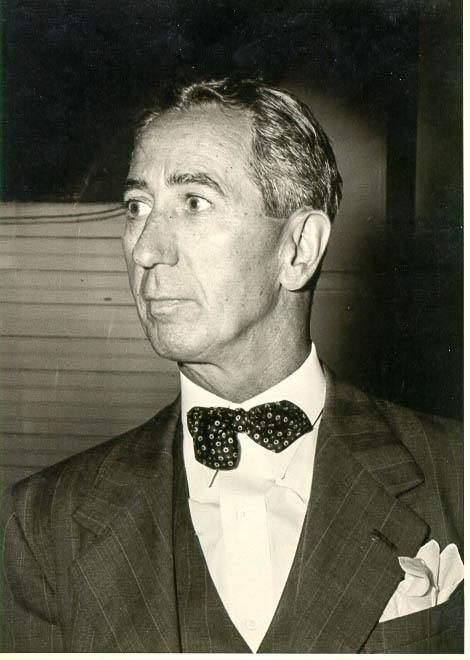

James Acklin, son of Grafton Acklin

James Acklin, son of Grafton Acklin

Acklin's business success had allowed his children to lead a fairly affluent lifestyle. The family lived in the fashionable West End district of Toledo, a community of extravagant Victorian homes. And as was common for the sons of Midwestern industrialists, all three Acklin sons received an east-coast, Ivy League education at Cornell University. James, the oldest at 27, graduated from college in 1906 and for several years worked with his father at the Toledo Machine and Tool Company.

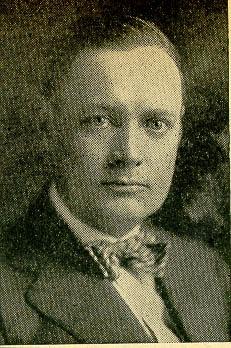

William, the youngest at 23, graduated from Cornell in 1910 and worked as a clerk at the Northern National Bank. Donald, the middle child at 25, had only a passing interest in the company and left shortly after its formation to pursue other career options.

Donald Acklin, Grafton's middle son

Donald Acklin, Grafton's middle son

So in the spring of 1911, Grafton Acklin, his sons, and Jerry Bingham – an outside investor – pulled together enough capital to found the Acklin Stamping Company. Grafton was the company's president, while James became Acklin Stamping's Vice President. The younger William was named the firm's secretary and treasurer. They opened up shop on the 1100 block of Dorr Street, using presses purchased mainly from Grafton's former company, the Toledo Machine and Tool Company. It was from these beginnings that Acklin sprang.

Drawing upon his extensive industrial business experience gained through his tenure at the Toledo Machine and Tool Company, Grafton Acklin's leadership quickly proved effective. Grafton's contacts in the metal working industry, as well as his strong sales and marketing ability, allowed Acklin Stamping to grow considerably in a fairly short period of time.

Picking up on the rising demand for automotive products, Acklin Stamping landed a job producing steel steering wheel spiders for automobiles. Acklin Stamping Company received production rights for an exclusive patent held by the Beck Frost Corporation and then supplied those steering wheel parts to the Willys-Overland Company.

As a job stamping plant, Acklin Stamping could hardly expect Willys-Overland alone to support them. In order to stay competitive, Acklin Stamping produced a wide variety of stampings for a large number of companies. At one point, the Ohio Gas Company asked Acklin Stamping to create a display case in which they could show off canisters of their oil at gas stations. Acklin Stamping agreed and stamped several thousand of them. After a brief trial, it was clear they weren't working out and the order dried up as quickly as it came.

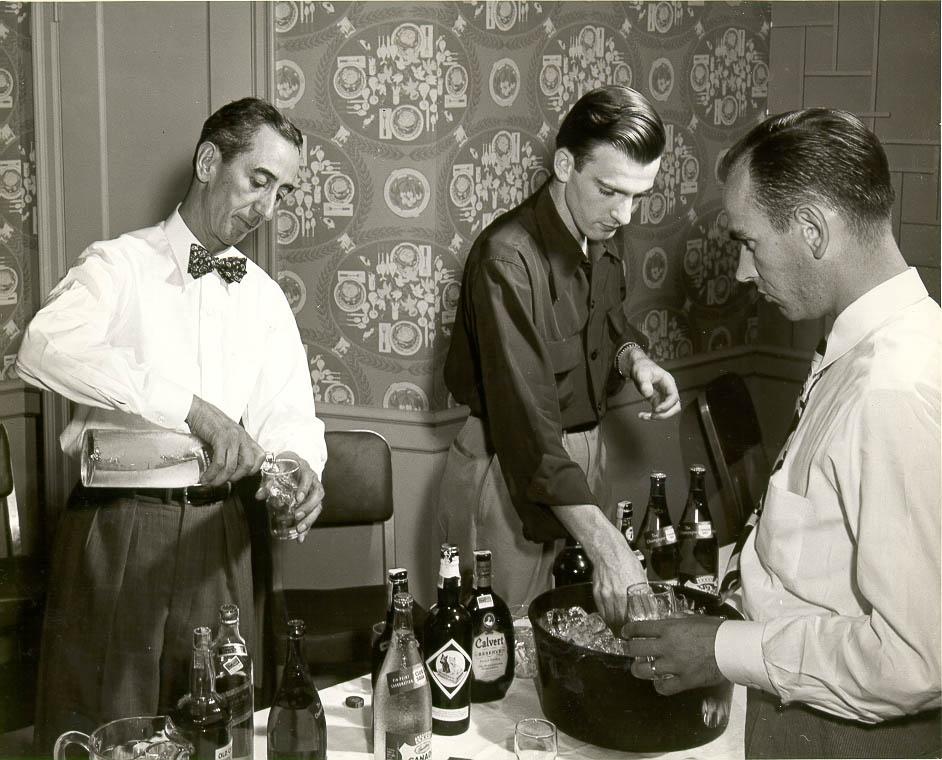

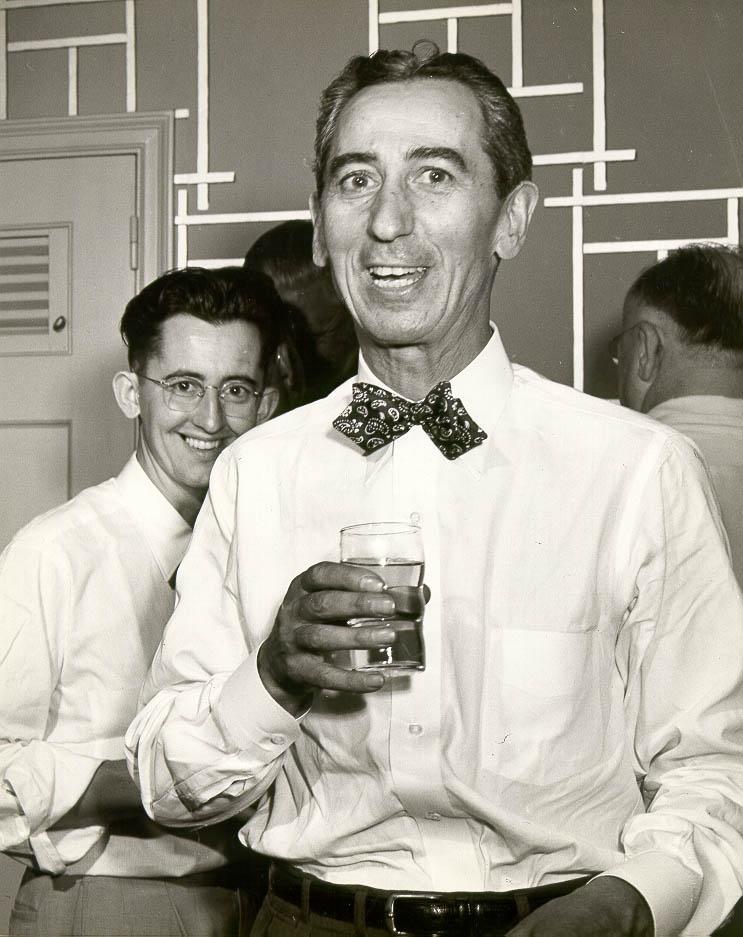

C.F. Greenhill pouring a drink. 1949 Salesmans Conference

C.F. Greenhill pouring a drink. 1949 Salesmans Conference

This shifting of production was fairly common. Without any one major customer, Acklin Stamping stamped an assortment of products during its early years including an order for muffler caps used in motorcycle engines. At the same time, they stamped everything from pulleys used in window sashes to metal vending machines used for dispensing Wrigley's gum and other candies. They stamped fuse socket holders, push lawn mowers, and metal splicers used in the repair of trolley car poles.

In the spring of 1917, when America declared war on Germany, beginning America's involvement in the First World War, Acklin was ready. The plant quickly shifted into the production of food containers, ammunition, and parts for Quartermaster trucks. By the time the war ended, Acklin had 125 presses, the largest of which was a 500 ton press, able to apply 500 tons of pressure to a single sheet of steel. The plant, then located in the 1600 block of Dorr Street at the corner of Woodland Avenue, shifted its production back to civilian goods.

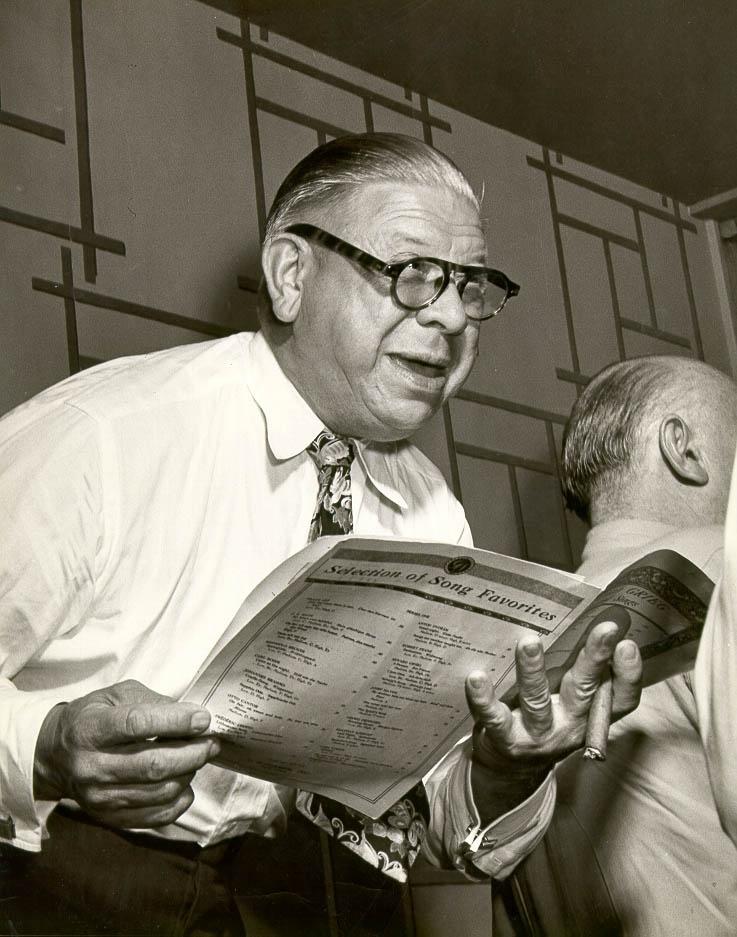

W.H. Dahlberg leading singing after sales conference. 1949.

W.H. Dahlberg leading singing after sales conference. 1949.

By 1925 the company's nearly 300 employees had outgrown the facilities of the 40,000 square foot Dorr Street plant and plans were made to build a new factory, this time on Nebraska Avenue. The new plant, built by the Toledo architectural firm of Langdon and Hohly, was nearly 90,000 square feet in size when constructed and was connected to the New York Central railroad. The new plant allowed Acklin to employ nearly 500 employees over the next year, cementing their role as one of the largest job-stamping plants in Ohio and the nation.

Following Grafton Acklin's death in early 1926, the company remained in the Acklin family’s hands. James Acklin, formerly Vice President of the company, stepped up to the presidency. James maintained the company's steady and substantial growth through the last half of the 1920s, and with a steady hand on the company's rudder, managed to weather the storm of the Great Depression.

But unfortunately, just as Acklin's business and the country's economy were beginning to recover under Roosevelt's New Deal, tragedy struck the family. In 1936, at the age of 52, James Acklin died in an automobile accident, leaving the helm of the company to his brother William. William ran the company without incident until 1939, when he passed away as well. Following the death of William Acklin, the company's holdings were transferred out of the Acklin family for the first time, marking the end of an era. Three Acklin executives, F.C. Greenhill; A.E. Seeman; and Frank Graper, divided the company between them. Frank Graper picked up where William left off, retaining the company's family name, and continuing its policies of promotion from within and respect and care for its employees, while Greenhill and Seeman remained in their respective executive positions.

II. The Depression -- "...during the Depression we got paid by Brinks Express, and was only paid $10.00. If we had more coming it was owed us..." -Frank Glyda, press operator, as quoted in The Acklin Press, 1975.

A. Toledo During the Depression

In the spring of 1929, Willys-Overland laid off the first of several thousand workers, bringing the abstract idea of the collapse of the New York Stock Exchange’s house of cards into sharp reality in the Toledo area. Willys-Overland was a major economic force in the Toledo area; the company’s $27 million payroll in 1925 represented about 41% of the city’s total annual payroll. The 1929 layoffs forced thousands of people into poverty, pushing the numbers of individuals receiving direct federal assistance to record highs. Although the jobless rate in Ohio reached 37%, in Toledo that number was nearly 80%.

The economic panic hurt many small companies and shops, forcing some to close and most to cut back workers. Acklin, however, though forced to lay off a fairly large number of workers, managed to keep its doors open and within a few years regained profitability.

The company’s president, James Acklin, met the demands of the economic crisis in a unique way. In October of 1930, he participated in a round table discussion for Iron Age magazine, as his company, like the rest of the industry, was coming to terms with their shared difficulties. During the course of this discussion James mentioned that, from his perspective, the depression had forced the company to become more efficient. He and his employees developed several radically new ideas in an effort to keep overhead at a minimum. One of these ideas included the shifting of presses around the plant's floor in order to allow the same operator to run several presses at once. Previously, presses had remained stationary and workers were used to take parts from one station to the next as it went through its production cycle. But what James and his engineers and employees developed moved these presses together, eliminating the need for workers to transfer parts by hand.

This re-combination of presses would occur for every new job the company received and could happen as often as 3 or 4 times a month. This innovation would be replicated during the next 30 years through increasingly mechanized presses, but at the time the innovation was a new one for the metal stamping industry. James went on to publish an article on the subject entitled “Migration of Presses Into Grouped Units” in the November, 1930 issue of Iron Age.

B. Employee's Tales of the Depression

The depression hit the company as hard as it hit the rest of the country. Jobs were scarce, but Acklin did better than many similar companies in the area. Homer Percival, a machine repairman for the Toledo Machine and Tool Company, was reduced to half time in 1929 following the stock market crash. In early 1930, Mr. Percival was sent to Acklin to repair a press. Since he could only work half days, it took him nearly a month to complete. On his last day, while heading for the door, James Acklin stopped him and offered him a full time position. Homer Percival accepted and remained at Acklin for the next 35 years, actively involving himself in the company and eventually becoming Acklin's general production foreman during the 1950s.

Frank Glyda, in the September-October 1975 issue of the Acklin Press, remembers his days at Acklin during the Depression. He was hired in 1929 and started on the presses earning 45 cents an hour. This dropped to 40 cents an hour in the early 30s. "During the Depression," he said, "we got paid by Brinks Express, and was [sic] only paid $10.00. If we had more coming, it was owed us. In fact, we could not exceed $10.00 per week." He also recalled never knowing how long he could expect to work when he came in. "You would come to work and really look for a job to do," he said. "The shortest day I ever put in was 6 minutes." Those six minutes of work were worth but a scant four cents.

Metal Stamping was very dangerous work, especially during these early years of the industry. Accidents were remarkably common, resulting often times in serious injury. Recognizing a need to concentrate attention on this issue, Egon Hirschmann, a production engineer, formed a Shop Safety Committee in 1930. For the next decade, Egon served either as head or as chair of this committee until a formal safety department was formed. The dangerous working conditions, among other things, were reasons that throughout the country unions began to form.

C. The Formation of the U.A.W. and its Acklin Unit

Willys-Overland, a leader in Toledo’s industrial community, joined the American Federation of Labor as the United Auto Workers Federal Union #18384 in February of 1934. In March of that year many other plants, particularly those who supplied parts to Willys-Overland, joined them, including Spicer Manufacturing; Bingham Stamping; and the Electric Auto-lite Company.

In April of 1934, the Electric Auto-lite company refused to recognize the Union and fired over 100 union workers, replacing them with strike-breakers. The pickets and protests became so violent that the National Guard was called in. On May 24, 1934, two Toledo strikers were killed during a scuffle between protestors and Guardsmen. Following the violence the strike was quickly settled, but led to the organization of the United Auto Workers International Union

Although Acklin never struck, union sympathy ran high. In 1937, led by 28-year-old Lewis Mattox, Acklin Stamping organized as a part of the U.A.W. Local 12. A vote was held by the National Labor Relations Board, a federal agency created just two years prior, in order to determine the level of employee support, and the results were unanimous -- 96% of Acklin Employees supported the formation of a union. Lewis, throughout his years at Acklin, remained active in the Union, serving on the annually elected Union committee nearly 30 times - over 12 of those times as Chairman - until his retirement in December, 1973.

Thanks to Lewis Mattox's strong leadership, the company and the union were able to co-exist in an almost model fashion. Lewis, and the Union, recognized that in order for the company to remain in business and remain competitive, costs had to be kept as low as possible. And as a result, they didn't make demands on the company's leadership that were unreasonable or fiscally unsound. By the same token, the management of Acklin understood that the workers had rights and needs. The company and the union jointly formed a safety committee consisting of both Union and company members. James Acklin had offered the company’s employees a retirement plan and disability benefits in 1934, well before the implementation of such programs on a federal or local level. Acklin also provided paid vacations, sick leave, hospital coverage, and other "fringe" benefits to its employees.

III. The War Effort -- "...because of your production on that day, the defeat of Japan has been brought closer..." - May 11, 1945 - Letter from the War Department to "the Men and Women of Acklin Stamping Company"

A. Toledo During World War II

When World War II began, Toledo was ready. In June of 1940, nearly a year before the United States entered the war, the Toledo Board of Education began to emphasize vocational programs for high school students in an effort to ensure that Toledo plants would receive defense contracts. Their efforts (and Toledo’s already present industrial base) paid off when, during the summer of 1940, Toledo industries began to receive defense contracts. In July 1940 the E.W. Bliss company, parent of the Toledo Machine and Tool Company, announced a $9.5 million dollar contract about the same time Willys-Overland announced a $25 million dollar contract. In all, Toledo received over $900 million dollars in defense orders, enough to put employment figures at the highest they’d been since 1929. Many plants, including Acklin, went to 24 hour, 7 day a week production.

With many men going to war, women began going to work by the thousands. In 1942, the first nursery opened in Toledo in order to meet the demands of mothers working in the factories. These women didn’t only work in factories, however; in fact, they filled a variety of positions from auto-mechanics and bus drivers to freight handlers for the Railway Express Agency.

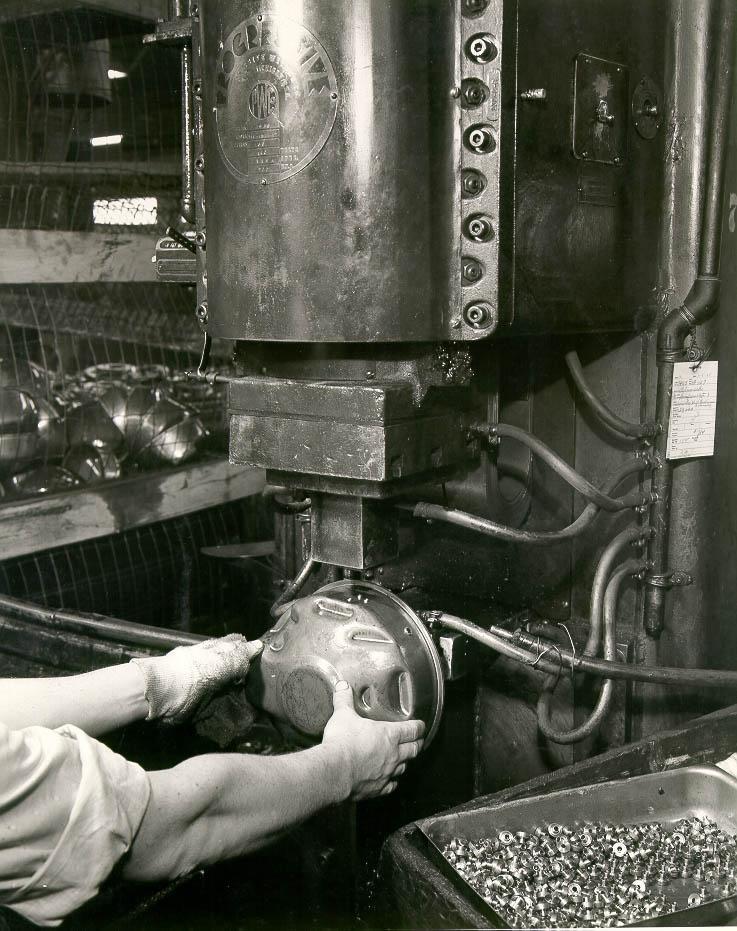

B. Acklin During World War II

During the mid 1930s, Acklin began experimental work for the Government on eye pieces to be used in gas masks. By the late 1930s, Acklin began to take production orders from the British and Swedish military governments for these eyepieces, as well as depth charges and other munitions. When America entered the war in December of 1941, Acklin's entire production was shifted to the war effort. In fact, the demand on Acklin was so high that the plant added an additional 25,000 square feet in 1943 to facilitate production.

Women working at Acklin during the war

Women working at Acklin during the war

For the war effort, Acklin produced a wide variety of products, but the bulk of their output was 20mm; 40mm; 75mm; and 105mm shell casings. The production of these shell casings required for the first time the use of automatic lathes. Rough forgings arrived at Acklin via New York Central Railroad from a variety of sources. It was Acklin's job to turn these into finished shell casings. The first step in this process involved hollowing out the centers of each shell. These shells were then turned on a lathe, roughly. A hole was bored into the nose of each shell, and then the nose of each shell was tapped, expanding the hole. Following that, the open end of each shell was shaped into a point and both ends were polished. A base was then welded to the face end of each shell before each nearly completed shell casing was turned on a lathe a final time. The shell casings were then subjected to rigorous testing before being heat treated, shipped, and packed.

Acklin also made parts used in Willys-Overland's trucks and Jeep production, 30 caliber machine gun mounts, the metal canisters used in flame throwers, and even parts that they found out later were used in the atomic bomb.

The work was difficult and many employees would later recall the constant observation and inspection and the long hours. Inspection was especially important on these parts because any error could create a shell which would not function properly, an error that could mean lives in the course of battle. Maintaining high levels of production with a fairly small number of employees resulted in long, hard hours for those who remained.

Ray Mierzwiak, who had worked for 18 cents an hour unloading coal cars during the Depression, was willing to take advantage of the work now available. He began putting in 14-hour days, 7 days a week, on the shell line. He earned $1.15 an hour, nearly a dollar more per hour than he had earned during the Depression. Many other employees put in long hours for the war production

effort, an undertaking which peaked in October of 1944 when Acklin had 175 people working in the production department - 103 women and 72 men.

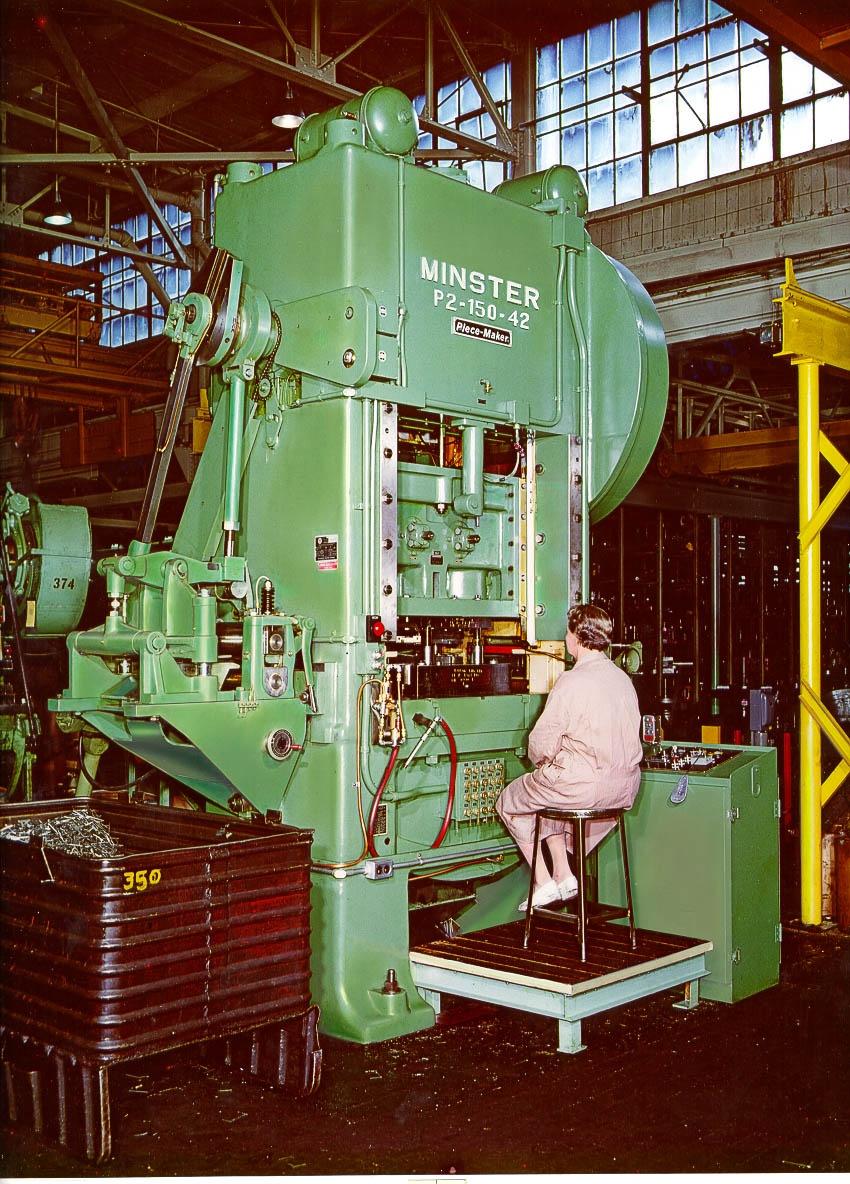

During the war effort, Acklin women, like women across Toledo and the country, worked alongside the men on the shell line, operating large presses, lathes, and dies. Previously, women had been relegated to working on the small lines, using smaller presses that could be operated sitting down to produce parts such as window sash pulleys and muffler parts for automobiles. During WWII, however, there was a shortage of males to operate the big line presses. Encouraged by government posters of Rosie the Riveter, women across the country and at Acklin stepped up to the job. Following the end of the war and the return of a large number of male workers, the women returned to the small line presses.

Acklin employees showed a remarkable dedication and earnestness in their production. In fact, in May of 1945, the War Department sent a letter of commendation to Acklin's employees, noting that "on V-E Day men and women of Acklin Stamping Company, without exception, remained on the job producing parts." The letter goes on to commend them, stating that unlike those who left their machines to celebrate "you people, with broader vision, and knowing that the hardest part of the job is still to be done, remained steadfast at your points of duty."

IV. The Greenhill Era -- 1944-1952

A. Rags to Riches - the C.F. Greenhill Story

In 1944, as the war came to a close, Frank Graper passed away following a brief illness, and C.F. Greenhill took the reins of the company. The story of Greenhill’s rise through the company ranks would make 19th century novelist Horatio Alger proud. Born in Surrey, England, Cyril F. Greenhill came with his family to a farm on the Canadian prairie. As a teenager, Cyril went to Banff, Alberta, a resort town in the Canadian Rockies, and got a job as a pack train guide. For his efforts he received $75 a month plus room and board. A Banff hotel guest who was struck by the 19- year-old's ability and ambition invited Cyril to return to Toledo with him.

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin President from 1944-1954, photo mid-1950s.

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin President from 1944-1954, photo mid-1950s.

C.F. Greenhill arrived in Toledo in early 1913, and he immediately took a $5 a week job at the Ohio Electric Car Company. Within two months, however, the car company closed its doors and Cyril was jobless. Fortunately, he had met a member of the Acklin family and was offered a job sweeping the plant's floor. Greenhill accepted and began work the day after Thanksgiving, 1913 for 11 cents an hour. During the next twelve years Cyril climbed his way up the management ladder, working nearly every job in the plant along the way: press operator, then die setter, machine shop worker, time keeper, and shipping clerk. From there he crossed over into management – becoming an office boy – and then moved to production control and into purchasing. When the Acklin Stamping plant moved from its Dorr Street location to Nebraska Avenue in 1925, Greenhill became a general superintendent, then a salesman under Harold Jay, and eventually, by the early 1930s, Sales Manager. In 1936, Greenhill was named Vice President in charge of Sales, and in 1939 was named to the Acklin Board of Directors. When W.C. Acklin died late that same year, the company's business holdings went to Greenhill along with Frank Graper and Mr. Seeman. Greenhill maintained his Vice Presidency under Frank Graper, and when Mr. Graper died in 1944, Greenhill took over the presidency.

B. The Acklin "Family"

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin's fifth President

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin's fifth President

Grenhill's experiences throughout the various parts of the plant gave him a firsthand understanding of the rigors involved in each of these jobs, and a unique perspective on the concerns and demands of his employees. He understood the importance of unity and how each of the units functioned together as a whole. Greenhill articulated all of this in a handbook published for new employees in 1949. The handbook reflects C.F.'s vision of Acklin Stamping as an extended family where "when we do our part and our best to cooperate with the other members of the family, we find that our own job as well as the job of our fellow worker is made easier."

Under Greenhill's leadership Acklin again became a close knit family organization, as it had been during the days under Grafton Acklin and his sons. It was not uncommon for several generations of the same family or even husbands and wives to work side by side at Acklin. Ray Mierzwiak started at Acklin in 1929 working in a wide variety of positions but ended up in Inspection, where he worked alongside his wife Bernice for 22 years. Harold Krueger's father, Clarence Krueger, worked at Acklin before him, serving as a Welding Supervisor.

Acklin put quite a bit of bread on the table for the Houston family. All four brothers – Marshall, Edward, Luther, and Samuel – worked at Acklin during the 1950s. The Houston family, being African-American, was somewhat unique at Acklin. Toledo’s African-American population grew during the 1940s, as many moved to the North to find work in plentiful factory jobs. African-Americans made up a fairly small percentage of Acklin's workforce, but they made invaluable contributions. Unfortunately, very few African-Americans were promoted to management positions within the plant. Acklin did, however, make a conscious effort to combat racism at the plant, running ads in the newspaper encouraging friendship and unity among all races.

Greenhill made an effort at Acklin, more so than ever before in the company's history, to hire and promote from within the Acklin family. It was stressed time and again during this period, in both the Employment Manual and in the Acklin Press, that with the right attitude and the right amount of hard work, any employee in the Acklin family could rise through the ranks much, as Mr. Greenhill did. And nearly every manager or executive level employee at Acklin under Greenhill had been at Acklin for over a decade, often on a production level.

C.F. Greenhill, Acklin President at 1949 Salesman Conference

C.F. Greenhill, Acklin President at 1949 Salesman Conference

Throughout Acklin's history, employees had been getting together for various social activities, from bowling leagues and golf tournaments to picnics. But in 1947, a group of employees joined together to organize the Acklin Activities Club. The group drew up a constitution, charged $1.00 annual dues and a $1.00 membership fee in order to build a treasury, and elected officers. The company pledged $5.00 for each new member, up to $1,000. The group quickly gained well over 200 members and received the full amount from the company. The Acklin Activities Club organized a wide variety of events open to all members, ranging from dart ball and ping pong to Baseball and Bowling leagues.

The Acklin Baseball team competed in the C.I.O. League against such teams as Gordon Bumper, Plaskon, Mather Spring, and Willys Overland. The Bowling Leagues were a huge success, drawing between 100 and 150 players. The league was organized within the plant and divided into four categories – men’s and women’s for both the night and the day shifts. At the end of any sports season a celebratory dinner was often held.

The club also held parties, most notably a late summer company picnic open to all members and their families, and a Christmas party held for Acklin children. The annual picnic, held at various parks, often swelled to between 600 and 700 Acklinites and their families. The day's festivities included horseshoes and volleyball, lots of food, and general fun. All levels of Acklinites, from high level management to production line workers, played side by side. In fact, the softball game between the management and the union was a perennial draw.

Also starting in 1947 was a group known as the 25 year club, so named because of its only membership criteria – 25 years of employment at Acklin Stamping. The nine initial inductees included one woman, Pearl Rutkowski, who worked on the small line for most of those 25 years. Other inductees hiring dates went back into the late teens and the very earliest days of the company's history. The new inductees were honored in a banquet, a tradition that would continue annually for several decades. At the first induction the men were given fine cigars, the women orchids, and all were given lapel pins and a round of applause. The club, open to both retired and current employees, grew quickly, drawing up a constitution and electing officers. By the end of the 1950s there were 117 members, 103 of which remained active Acklin employees.

1947 also marked the arrival of The Acklin Press, a company newspaper that was published monthly. Edited by Robert Keller, personnel director, it kept Acklin Employees appraised of events and news around the plant. The Acklin Press covered all Acklin sporting events from the bowling league to fishing club, as well as documenting social events. It also described the business outlook of the company and the various parts being made. Designed for the entire family, the Acklin Press included in the center a "Family Fun Page" which contained cartoons and games for the children, as well as trivia, crosswords, and movie gossip for adults. The paper would continue monthly publication for the next several decades before finally succumbing to shrinking finances and gradually disappearing.

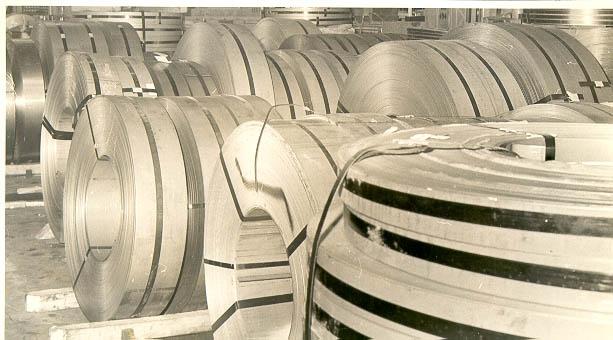

Steel Rolls as Raw Stamping Materials

Steel Rolls as Raw Stamping Materials

Under Greenhill, the company and the Union worked together to forge several projects beneficial to employees, including a company credit union; a more comprehensive pension and retirement plan; insurance plans; and paycheck deductions for savings bonds. Acklin pioneered many of these programs for the Toledo area and each of these programs provided Acklin employees with a variety of options and protections they didn't have before. These programs were negotiated through the union contract, and many of them expanded employee benefits and coverage throughout the years.

As a result of these programs and opportunities, Acklin became and remained a very close-knit organization, with employees spending time with one another both on and off the clock. Acklin was a family organization, one that encouraged loyalty, dedication, and hard work. Greenhill was a respected president and under his leadership the company's employees thrived.

C. Veterans Come Home

As World War II ended, many Acklin employees who had left to join the army began to return home to their jobs. Many women who a few years earlier had been working on the "Big Line" producing shell casings left to get married – often to returning Acklin veterans – and start families. The women who remained at Acklin shifted to clerical work or small line production.

The number of men returning to America looking for work was rather large. Many former Acklin employees returned to their old jobs, but as Acklin expanded to meet the demands of the civilian market (including the quickly growing refrigeration and air conditioning industries), quite a few new faces were hired as well.

Bernard Sztukowski worked in the die shop at Acklin before joining the Army's amphibious forces. He spent two years in the Pacific participating in three major and battles and was aboard the U.S.S. Missouri to witness the surrender of Japan on August 14th, 1945. He returned to Acklin in 1946 and married his fiancée, Lenore Muck, one of Acklin's two nurses in the First Aid room. He would remain at Acklin working in a variety of capacities.

Steve Przybylski, who he worked at Acklin since the depression, became a corporal with the Chemical Warfare Unit and played a part in four major battles in France, Germany, and the Rhineland during the war, including the Battle of the Bulge. Eugene Chapman also saw significant military action, serving for two full years in the Navy on an aircraft carrier in Manila Bay. He took part in seven major battles and his ship was hit twice by Japanese suicide planes.

Not every Acklin veteran saw as much action during the war as Bernard, Eugene, and Steve did. Some, like Les Carr, who entered in 1943, were bounced around the United States. He went to Miami Beach for basic training, then spent six months in Camp Campbell in Kentucky. From there he joined a Military Police outfit and spent the next year and a half between March Field, California and Abilene, Texas. Following his discharge in October of 1945, Les returned to Acklin.

Homer Percival, Acklin's general production foreman and an 18-year Acklinite, received a draft exemption based on his importance in and knowledge of Acklin's business. He instead served on the Selective Service Board, sending many of Acklin's employees off to the war – including Robert Keller, editor of the Acklin Press.

Not everyone returned from the war in the same shape as when they left. Harold Krueger enlisted in the Navy in 1942 and was sent to Machinist's Mate Service School in Dearborn, Michigan. Upon completion of the program he joined a ship and sailed through New Caledonia, New Guinea and the Admiralty Islands, serving as a machinist. In March of 1943, however, his leg was crushed between his ship and a tugboat. He spent over two years in Navy hospitals in the Pacific recovering from his injuries before finally returning to the United States in May of 1945. Harold recovered well from his injuries and would remain at Acklin for over 40 more years, eventually becoming plant manager during the mid-1980s.

-ORAL HISTORY NARRATIVES

D. Post War Production

Acklin Stamping Plant, 1946. 115,000 square feet.

Acklin Stamping Plant, 1946. 115,000 square feet.

As war time production ended, Acklin expanded its domestic production rapidly. The influx of experienced workers and a growing demand for consumer goods such as washing machines, refrigerators, and air conditioners caused rapid expansion at Acklin. In 1947 there were 475 employees, double the amount employed there three years prior during the peak days of the shell line and nearly as many as during the period of prosperity in the late 1920s.

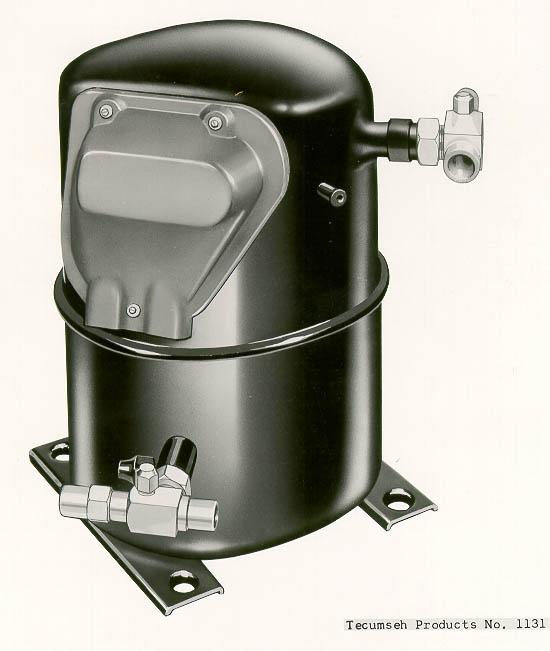

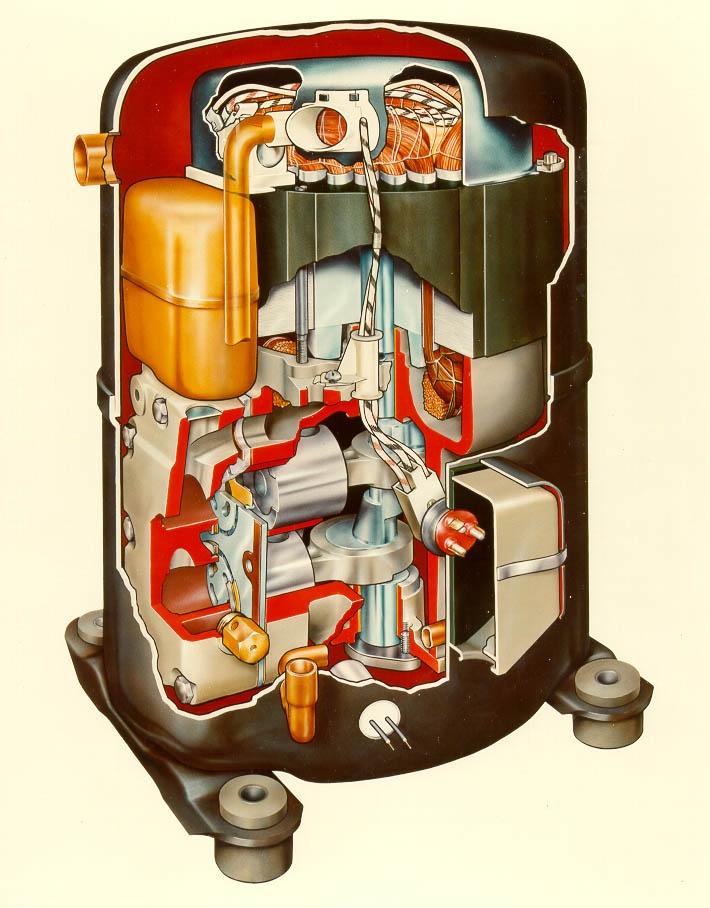

Shortly after the war, Acklin began to take orders from the Tecumseh Products Corporation of Tecumseh, Michigan. A leader in the compressor industry, Tecumseh had Acklin stamping compressor housings for use in the rapidly growing fields of refrigeration, air conditioning, and other cooling systems. Acklin also took large orders for parts from the Bendix Washing Machine Company of South Bend, Indiana.

During this period, Acklin was actively involved in seeking out new orders in an effort to supplement and maintain production levels. The rapidly expanding economy, particularly for domestic consumer goods, created a great deal of competition between various firms for the larger, steadier jobs.

When the Korean War broke out in the early 1950s, Acklin hoped to claim a large number of defense contracts, as they had during World War II. However, things didn't work out quite as they expected. During 1951, the Acklin Press reported that 95% of the orders placed by Acklin were for defense or war materials. Very few of these were produced, however, and most Acklin work remained civilian.

There was also a great deal of pressure placed upon the steel supply, with much of the higher quality steel going to the automotive industry, which was producing automobiles at a record rate. Some companies, when placing a stamping order with Acklin, would provide their own steel as well, but this was a fairly rare occurrence. Occasional labor disputes in the coal mining and steel industries would also hurt supply, forcing prices up. Or, if strikes seemed imminent but never materialized, Acklin was often left with an overstock of steel, which would force up production costs.

These pressures created the need for dedicated and concentrated effort on quality control for the jobs already received and a certain degree of fluctuation of employees. The air conditioning business itself was fairly cyclical, with production peaking in the late winter months in an effort to prepare for summer demand. Acklin had a policy for these inevitable summer layoffs that was based on seniority and rank; those who were laid off were placed on a list and they were the first individuals hired when production demands increased in the fall. Despite these fluctuations, Acklin remained one of the largest and most productive stamping plants in the Toledo area.

In 1947, Acklin's plant was 115,000 square feet in size, housing 150 presses and using 18,000 tons of steel per year. 35% of Acklin's business still relied on the automotive industry, supplying parts used in Willys-Overland, Studebaker, Chrysler, and GM cars. Another 35% of Acklin's business – approximately 4,000 units per day – went into the production of compressors and compressor parts used in refrigeration. Acklin also stamped parts for household appliances – washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and air conditioning – production that comprised 20% of Acklin's output. The remaining 10% was invested in the production of agricultural and other miscellaneous stampings.

Tecumseh wasn't the only company Acklin stamped compressor housings for. They also produced parts used in compressors assembled by General Electric and Westinghouse, but Tecumseh Products became an increasingly important source of business. In January of 1949, rather than lose Tecumseh as a customer, Acklin cut their prices on housings by 14 cents per unit, representing a significant loss of profit.

In 1950, Acklin began the production for Tecumseh Products of pistons used in the assembly of compressors. The pistons were designed through a joint effort of both Acklin and Tecumseh Engineers and this new job order provided 25 new jobs, mainly on the small press lines. This and other similar ventures show the co-operation and co-dependence the two companies were quickly forming.

In late 1951, Acklin was still searching widely for outside orders to increase their production and provide enough work to maintain the number of employees, but layoffs were inevitable. Several parts Acklin was producing had been underbid on in order to receive the order and the works involved, but were losing money on fairly rapidly. Steel was scarce and workers were uneasy about job security. Finding themselves in an increasingly complex and chaotic industrial marketplace, they began to attach increasing importance to Tecumseh's steady business.

E. Growing Consolidation - Toledo Industry in the 1950s

During the 1950s, many of Toledo’s industries underwent consolidations, mergers, and expansion. In 1953, Willys-Overland Motors Inc., still one of Toledo’s industrial leaders as its trademark defense product – the jeep – was becoming increasingly popular domestically, was sold to the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation for $62 million dollars, becoming the Willys Motor company. Doehler-Jarvis, a parts manufacturer, merged with the National Lead Company in 1953 as well. In 1957, two of Toledo’s oldest industries, the Haughton Elevator Company and the Toledo Scale Company, merged.

These mergers were fueled by a number of factors. First, increasingly sophisticated travel methods made it possible for goods to be manufactured in one area and cheaply shipped to another. This increased the importance of economies of scale – if you can produce large numbers of a product in a uniform manner, you can produce it and ship it more cheaply than your competitors. In order to remain competitive, large multinational corporations began to form, joining together older, more traditional businesses. These larger corporations began to compete on a national and international scale. Another reason for these conglomerations among the manufacturing sector was ever increasing technological change. New machines had to be purchased at an ever-increasing rate to stay competitive with other plants. In order to afford these purchases, larger corporations with larger profit margins were necessary.

IV. Tecumseh Products Steps In, 1952-1964

A. Tecumseh's History

The Tecumseh Products Company actually started in Hillsdale, Michigan in 1932, 21 years after Acklin was formed. In that year, Raymond Herrick and two of his friends formed the Hillsdale Machine and Tool Company, an organization devoted to the manufacture of automotive parts. They had, however, an idea for better refrigeration parts and in 1934 they purchased a 50,000 square foot plant in Tecumseh, Michigan and changed their name to Tecumseh Products. In 1938, they brought out the first hermetically sealed refrigeration unit, but this line of business was sidelined for war production in the following years. By 1947, Tecumseh was a leader in the refrigerator compressor industry. In November of 1950, they purchased the Universal Cooler Company of Marion, Ohio, branching out into the air conditioning business.

In July of 1952, Tecumseh Products announced its purchase of the Acklin Stamping Plant. Tecumseh had originally planned on building a new plant in Michigan and moving Acklin's employees and equipment, but Acklin refused, not wanting to "break a good organization," so the company stayed in Toledo. Initially, there were no changes to the company’s management structure. Several Acklin executives took positions on Tecumseh's Board of Directors, and Tecumseh's President and Secretary took positions on Acklin's board.

B. Acklin Production Under Tecumseh, 1952-1954

Essentially becoming Tecumseh Products in-house stamping plant, Acklin's production of Tecumseh-related goods expanded, quickly becoming the bulk of Acklin's output. Acklin continued to stamp a variety of other outside parts, including parts for major automobile manufacturers. These other stamping jobs helped to stabilize the cyclical production schedule involved in the production of air conditioners and refrigerators.

Following World War II, rising incomes and lowered prices created an increased demand for a wide variety of luxury goods. Technological advances made by the government during the war were utilized for the first time in such civilian goods as air conditioners, refrigerators, automobile engines and bodies, and televisions. Tecumseh was uniquely positioned to capitalize on this growing demand, and their business grew dramatically.

Air conditioning production began in the winter with maximum output coming in February, March, and April in order to send these casings to assembly factories where they would be included in the actual units, ready for sale during the hot summer months. August was the slowest time for this production and as a result the plant would shut down for two weeks each August, during which time a majority of the employees would take a vacation while some would do general maintenance, repair, and improvements work on the plant.

In 1953, as the demand for refrigerators and other cooling devices increased, Tecumseh approved approximately $45,000 in plant expansions and new machinery purchases in order to increase output. To accommodate these new orders, Acklin ordered more expensive steel than they usually used and hired a large number of new employees. But skilled employees were hard to find. Following the war, many returning veterans went to college and took jobs above the factory production level, and more and more high school graduates were following the same path.

The spring of 1953 saw the Big Line busy producing housings for room air conditioners. Sales of these appliances were up from previous years and Acklin was there to meet the demand.

C. Acklin Becomes a Division of Tecumseh Products -- Greenhill Steps Down, 1954

In 1954, the Acklin Stamping Company became the Acklin Stamping Division of Tecumseh Products. In the turnover and re-alignment, President Cyril Greenhill left the presidency, retaining his position as the Chairman of Acklin's Board of Directors. In his place, Alvin E. Seeman, an Acklin employee since 1929, assumed the presidency. Ralph Meyer became the company's Treasurer while Harry Smith, Vice President in Charge of Production since 1944, remained in that position.

Alvin Seeman began his career 1920 as a treasurer at the Dura Corporation. He left Dura in 1924 to become a Senior Accountant at the firm of Knopak, Hurst, and Dalton. He came to Acklin in 1929 and served as an auditor, and over the next 8 years he worked his way up to the Treasurer position. In 1940, he was made a Vice President of the company while retaining his Treasurer duties. In 1944, he was promoted to Executive Vice President, and when Tecumseh purchased Acklin in 1952, he became a member of Tecumseh's Board of Directors while retaining his position at Acklin.

Seeman’s official title, reflecting Acklin's new position in Tecumseh's corporate hierarchy, was Executive Vice President of Tecumseh Products, General Manager of Acklin Stamping Division. Effectively, Acklin no longer had its own President, but merely a Tecumseh Vice President in charge of the Acklin Division.

Under Alvin Seeman's leadership and through Tecumseh Product's financial investment, Acklin entered a new period of economic stability during the second half of the 1950s. The transition to Tecumseh Products benefitted Acklin in a number of ways. Raymond Herrick, Tecumseh’s President at the time, had, like Greenhill, worked his way up from the ground floor. As a result of this he saw and understood the needs of the workers and tried hard to foster a sense of community and kinship among all of Tecumseh’s employees.

Cordia Ross, a press operator on the small line during this time, remembered Herrick:

“We used to call him the Big Man, you know. He used to give us turkeys for Christmas.... and he said he gave us turkeys for Christmas so we would have something on our tables for the holidays because when he was growing up they were poor and they couldn’t afford turkeys.”

Tecumseh also supplied Acklin with steady work, at least during the 1950s and 1960s, allowing them a sort of stability and regularity they hadn’t had since World War II. Tecumseh’s capital investments allowed Acklin to remain competitive with new machines and equipment.

In 1955, under Tecumseh Products, a safety program was introduced. Large amounts of money were put into upgrading presses, providing safety gear, and promoting knowledge of safety among the workers. This program was a dramatic and immediate success, with the number of lost time days due to industrial injuries (those significant enough to require medical attention) dropping from an average of 5000 per year from 1950-1954 to 498 in 1955.

A new labor contract negotiated in 1955 between Tecumseh and the union was described by Lewis Mattox, union chair, as the best contract ever negotiated at Acklin. The terms of the contract included comprehensive hospital coverage, disability provisions, and the availability of discounted life insurance for employees.

The 1957 contract that would carry the company through the decade went even further. After a 30-hour bargaining session, Tecumseh granted each of Acklin's 600 employees at least a 7 cent per hour raise, and an even larger amount for 170 skilled workers. The contract also provided increased vacation pay, and increased sickness and accident benefits. All of these provisions were fairly expensive, costs which were offset by ever increasing production and rising profits.

Production and profits were indeed booming for Acklin and Tecumseh during the late 1950s and early 1960s. In the spring of 1956, using nearly 5,000 pounds of steel per hour, the plant was producing at nearly 100% capacity. This production set records for Acklin. During the months of March and April, over 35,000 compressor housings were made each day, for a total of 766,000 housings in March and 742,000 in April. By October of 1956, Acklin employed 650 individuals, had a monthly payroll of $250,000, and used 160 tons of steel each day.

This period of rapid expansion and increased production continued until 1959, when a major steel strike, colder weather, and declining demand forced a fairly severe round of layoffs - 61 men and 18 women. By 1961, the average pay at Acklin was up to 2.49 per hour, a decent salary, but including benefits provided through the labor contracts that salary cost Tecumseh 3.33 an hour, well above the local or national average.

Tecumseh had established itself by the early 1960s as America's largest producer of compressors, making 70% of the compressors used in window air conditioners, 70% of the compressors used in automobile air conditioners (outside of GM, which made its own), 70% of freezer compressors, and 30% of refrigerator compressors. The number of units sold annually climbed for Tecumseh from 356,000 in 1941 to 5,659,000 in 1962. Sales increased as well, growing from $7 million a year in 1941 to $184 million in 1962. Tecumseh Products had clearly grown from the small company in Raymond Herrick's garage into an important international business.

During the late 1950s, in an effort to diversify its holdings, Tecumseh Products purchased several smaller companies in a variety of manufacturing fields. It picked up the Lauson Engine Company and Taylor Products in 1956, both manufacturers of gasoline engines. In 1957, Tecumseh bought out the Power Products Company of Grafton, Wisconsin, known for its production of two cycle engines. The Ohio Semi-Conductor company of Columbus, Ohio was purchased by Tecumseh in 1960, and the Peerless Gear and Machine Company of Dunkirk, Ohio followed a few years after. This diversification allowed Tecumseh to cope with the both the cyclical nature of compressor production and provided them with alternative business as the refrigeration market shifted out of its explosive first decade to become an item purchased mainly by replacement buyers and newly-married couples.

During the 1950s, Tecumseh Products also became increasingly involved in the international market. Rather than produce compressor housings domestically and then export them to Europe and the rest of the world, Tecumseh Products opted to franchise its designs to other companies. Tecumseh would provide, for a substantial fee, the drawings and plans for the construction of these compressors to an independent company. Tecumseh would then provide training and consulting expertise to the new company and would also receive a royalty percentage of that company’s profits. This business model, although it didn't affect Acklin's production directly, allowed Tecumseh to achieve high profitability.

Employment and work continued steadily throughout the early 1960s. During this period Acklin maintained between 600 and 700 employees, depending on the season and production demands.

In 1965, Alvin Seeman, after nine years at Acklin's helm, relinquished his position as General Manager at Acklin to Phillip Wood. Seeman remained an Executive Vice President of Tecumseh Products, however, and a member of Tecumseh's board. This transfer of power marks another important shift in Acklin's history.

VI. Stability and Decline 1965-1982

A. Phil Wood, Plant Manager

Phillip C. Wood came to Acklin in 1942 from The University of Toledo's engineering school. During the war production effort Wood had worked as a metallurgist on the shell line. From there he moved to the estimating department, then standards, before entering the engineering department. During the early 1950s, Wood served as a production engineer before being promoted to Chief Engineer. By 1955, Wood had moved up to the position of Plant Manager, overseeing the efficient operation of the plant's production effort on a day-to-day basis.

In 1965, the year Wood was appointed to the Plant Manager position, Acklin Stamping hit a brief period of slowdown. During the early months of the year, a steel strike seemed to loom on the horizon; as a precaution, Acklin overstocked its supply of steel and when the strike didn't occur the company was left with a large amount of expensive steel. This, combined with a cool summer and a slowing demand for refrigerators, caused layoffs in the late summer and early fall of 1965.

Production began to climb slowly through 1966 and 1967. A strike at Tecumseh Products in 1968 slowed work down for a few months but by 1969, production was again at full tilt. The first large surge in production from the late 1940s through the late 1950s was connected to the rapid expansion of the refrigerator market. However, by the mid 1960s, this market had begun to shrink. The late 1960s saw a period of growth in the air conditioning market as more and more Americans purchased units for their cars, homes, and businesses. As a result, 1968 and 1969 were extremely busy years, with Acklin producing between 30,000 and 40,000 compressor casings daily for sales of 19 million dollars each year.

B. The 1970s - Problematic Prospects

Acklin's prosperity continued into the early 1970s. Tecumseh's investment from 1966-1970 of nearly 1 1/2 million dollars into new equipment and buildings for Acklin kept the company on the cutting edge of technology. Demand for air conditioner compressors remained high and business was good. In December of 1970, Acklin stamped the 100 millionth compressor housing made at the company, nearly 75 million of which were produced following Tecumseh's purchase of Acklin.

Acklin Stamping Plant Aerial Photo, 1970s.

Acklin Stamping Plant Aerial Photo, 1970s.

But things would never again be so good. In 1971, the first signs of a nationwide recession began to appear. Foreign imports, which sold far more cheaply than domestic goods, began to cut into the demand. Increased automation began to eat away at the number of workers required to produce the same amount of output.

The introduction of safety laws and the formation of OSHA, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in 1970, created yet another economic hurdle Acklin had to leap. In order to bring all of their equipment into compliance, large capital investments had to be made, money that otherwise would go to new equipment. Acklin's own safety program, which was begun by the union and the management in the early 1950s, as well as increasingly automated machinery, had already created a reduction in accidents.

In 1972, Tecumseh spent $350,000 on capital improvements, including safety modifications; electric lift trucks; and new housing washing machines.

By the mid 1970s the energy crisis had begun to affect Acklin. Increasing fuel prices drove up the costs of operation and furthered the demand for more efficient and automated presses. These changes caused Acklin to form an Energy Conservation Committee in 1973. The committee was made up of both management and union leaders and was in charge of finding solutions to the problems presented by the energy shortage. Their recommendations included cutting back use of natural gas and instead using heating oil, and better utilizing heat sources within the plant -- during the cold winter months, they placed fans near the machines to distribute that heat, rather than running the furnace.

Throughout the rest of the decade, regardless of their efforts, material shortages and a decreased demand caused dramatic reductions in Acklin’s work force and Tecumseh's profits. As a result, starting in 1975, a large number of management and supervisory jobs were combined, eliminated, or re-assigned. Employees were forced to increase their efforts of decreasing scrap and increasing productivity.

Throughout the remainder of the 1970s, Acklin was held to a gas and fuel oil quota based on their 1972 usage, a restriction that forced them to cut profits. By 1979, a Federal Energy Regulation was handed down which demanded that the company set the temperature no higher than 65 degrees.

Woman operating Minster Press, 1970s

Woman operating Minster Press, 1970s

VI. Hard Times - 1983-1998. “With Whirlpool getting out of the compressor business, we expect to see more and more foreign compressors in U.S. room units.” -William E. Macbeth, President of Tecumseh Products, 1983.

By the early 1980s, employment had slipped to under 100 individuals for the first time since the company's founding. In 1982, as a part of an executive consolidation at Tecumseh, Phil Wood was promoted to Group Manufacturing Manager - Compressors. He was in charge of the operations at the Marion, Somerset, Acklin, and Tueplo plants and his office was moved to Tecumseh's headquarters.

Harold Krueger, a second-generation, 37-year employee, was named Acklin Plant Manager. Under Krueger a series of meetings called Employee Information Conferences was established in an effort to open communication between the employees and management.

The Acklin Press, a 37-year-old publication, ended its run 1984 due to budget cutbacks.

In 1983, Krueger announced the recall of 51 hourly and 4 salaried employees. These additions doubled the number of employees at Acklin, for a time. Tecumseh also approved $316,200 in capital improvements used for improved equipment and building expansion.

There was a shift in Tecumseh Product’s production policy in 1983. The company had long held to the ideal of using solely American labor for compressors sold in the United States. But when Whirlpool stepped out of the business, a gaping hole was left that was quickly filled by a flood of cheaper foreign imports that could be produced abroad and shipped to America for a third of the price of domestically produced units. As a result, Tecumseh Products began to turn increasingly towards overseas production in an effort to cut costs and remain competitive.

The previous advantages held by American firms like Tecumseh over foreign companies were rapid technological improvements and highly trained and efficient workers. But as William Macbeth, Tecumseh’s president said in a 1983 interview, “engineering improvements [were] not enough to make a difference.” Technology involved in the production of compressors had by this time become so finely honed that these improvements were hardly enough to make a difference between units, and cost became the deciding factor. As a result, Tecumseh began to shift some of its production overseas.

As a result of these shifts, Acklin’s output and profits began to drop. The company’s financial situation continued to decline, operating in the red for much of the mid-1980s. In February of 1986, the issue came to a head when Acklin’s 110 hourly employees went on strike. Tecumseh Products and Acklin’s management seriously considered shutting down the plant and refused to give in to the worker’s demands for increased wages.

The strike ended after two weeks on February 22, 1986 without any wage concessions on the part of the company. They were able to reach an agreement with the union, however, reducing the number of job classifications at the plant from over 35 to 13. This shift allowed workers greater flexibility, reducing their downtime and effectively increasing their pay. Previously, after finishing their assigned tasks, workers would remain idle for several hours, since the high number of job classifications prevented them from doing other work they were capable of.

The company during the mid-1980s was not profitable, but by following these work rule changes and “a greater effort,” Acklin “reduced costs and was able to add jobs,” Ray Cox, Acklin General Manager, said in a 1988 Toledo Blade article. By the late 1980s, the company saw the recall of 30 of their laid off employees, increasing the workforce to 139 hourly positions. A heat wave during the summer of 1988 depleted supplies of air-conditioners around the country and increased Acklin’s production from 2.5 million in 1987 to nearly 3 million throughout 1989. Acklin’s business was also increasing during this time due to a weak dollar and strong international sales.

The company during these years also began a dedicated effort to find work, in Ray Cox’s words “from other companies that use compressors or any others that use stamping that requires deep-draw stamping expertise.” These efforts, however, were largely unsuccessful. There hadn't been a sales department at Acklin since the merger with Tecumseh Products in 1954. As a result, getting new contracts was rather difficult and the entirety of Acklin's output remained with Tecumseh Products.

B. Less tension, less business

When Bob Housch was assigned by Tecumseh Products to take over the position of Acklin's Plant Manager, many employees felt that this marked a change in the relationship between management in the front office and the union workers on the floor. Housch was a retired production operator who had brought troubled plants through difficult times in the past. He emphasized cooperation between the union and management, hosting seminars and forming teams that included both union and management employees.

In 1992, as part of Housch's new commitment to better employee relations, he invited the Cumberland Group to perform an anonymous survey of 65 of Acklin's employees. Asking a wide range of questions on a variety of topics, the survey was able to uncover the deep tensions and dissatisfaction that ran through the company. Among the problems described was a sense of tension between the management and the workers and a reluctance for accountability at all levels. Acklin employees felt that they were being held to higher standards than other Tecumseh divisions.

The employees also noted a lack of long term goals or planning and felt that the plant was operating on a day-by-day mentality. They were concerned by a perceived lack of leadership over the past decade and felt that this had contributed to a low sense of pride in Acklin and in Acklin- produced products.

As a result of this survey and efforts made on both sides, things began to improve between the union employees and the Tecumseh management representatives present at Acklin. However, Tecumseh Product's corporate management felt that Bob Housch was, according to a union committee member at that time, "too easy on us."

Despite these improvements in management-employee relations, economic pressure continued to weigh heavily on Acklin in particular and the metal working industry at large. Decreasing profits, increased automation, and ever-increasing globalization of the industrial labor market continued through this period. Tecumseh's worldwide divisions were quickly becoming increasingly important to the company's bottom line, just as foreign-made compressors continued to undersell domestically produced items.

In the fall of 1998, Tecumseh Products told Acklin employees to take a $3.75 per hour pay cut or face closure of the plant. In a vote on the proposed contract, Acklin employees turned it down by an overwhelming 106-3 margin. They refused, as one employee put it, to "take chances of getting fingers and hands cut off for McDonald's wages," continuing, "when we were in negotiations I went by a McDonalds in Wauseon and it said 'Now Hiring, Full Benefits, $8 an hour.' Well, we didn't even have full benefits."

At the time of the decision, Acklin employed a little more than 100 employees. In November of 1998 half were laid off, leaving an equal number to ride out what looked to be the end of Acklin Stamping.

VIII. 1999- Hope for the Future!

A. Howard Ice's Vision

With less than two months before the slated closing of Acklin Stamping, Howard Ice, Jr., a young businessman, and Lloyd Mahaffy, regional coordinator of the UAW, put together a plan to save Acklin Stamping. With the help of Donald Kuhl, a partner in the law firm of Eastman and Smith, Ltd; Mike Miller of Fifth-Third Bank, the First Energy Corporation; the city of Toledo's Economic Development team; the Toledo Lucas County Port Authority; and the Regional Growth Partnership, they were able to secure $2.9 million dollars. With this funding, they were able to purchase the 172,000 square foot factory and much of the essential machinery, thereby transferring the company back to private hands for the first time since 1952.

Howard Ice came to Toledo after graduating from Ohio University. He worked first as a cost accountant at a local stamping company before moving up through purchasing and production control positions to eventually become a plant manager. Ice described his management philosophy to a regional business magazine shortly after the purchase was finalized: "I grew up in a blue-collar family and learned no one is better than anyone else. It’s just that some people have different levels of responsibility. Everyone has thoughts and wishes to be heard. They all want to improve the business."

Acklin continues to stamp compressor housings for Tecumseh Products, but a sales department headed by Phil Carron is aggressively pursuing new business with measured success. Ice plans to diversify the products Acklin’s products, hoping to branch out into automotive and other sectors. In order to accomplish this, Ice has begun to introduce high standard technology and processes to Acklin.

Working with Lloyd Mahaffey and the UAW, Acklin under Ice has helped create a self-directed workforce. Utilizing the knowledge and desire for success within the employees, this system allows for maximum flexibility with minimum supervision. Ice said, "at first it was a shock to many employees. They would say 'I'm not sure what my boundaries are,' and we would tell them, 'you have no boundaries.'” Ice's goal is to have his employees feel important, to make them "enjoy coming to work."

There is a sense of cooperation and team play between management and the union that hadn't been present at Acklin for some time. Linda Straub, chair of Acklin's union committee, states, "They're trying to run a business and we're trying to help them run a business."

Within Acklin's employees there is a sense of creation, of new hope and new possibilities. "We feel like we're creating something and we are," Linda Straub said, continuing, "It’s not often that you get to be in on the ground floor of something."

Acklin's employment now fluctuates between 20 and 40 employees, but with growing business, Ice hopes to raise that number to 65 or higher within the next several years. Ms. Straub sums it up best when she says, "with Howard I see a future...and I think we're going to go far."

After 89 years, radical changes have washed over the metal working industry and Acklin has grown and changed along with them. Acklin's story and course through the last century is not unique, and the stories and events at Acklin could be retold at hundreds and thousands of plants like it throughout the region and the country. Acklin is starting anew, heading into a new era, and with dedication and cooperation they're ready for whatever comes their way.

Faces of Steel: People and History of Acklin Stamping Plant, Toledo Ohio

Visit the original virtual exhibition created in 2000 by UT student Benjamin Grillot. It was one of the earliest virtual exhibition at the Ward N. Canaday Center for Special Collections. [Exhibit link]

Acklin Stamping Company Records, 1911-1997, MSS-139 [finding aid link]

Acklin Stamping Company Records, 1911-1997, MSS-139 [digitized records]