IV. The Greenhill Era -- 1944-1952

A. Rags to Riches - the C.F. Greenhill Story

In 1944, as the war came to a close, Frank Graper passed away following a brief illness, and C.F. Greenhill took the reins of the company. The story of Greenhill’s rise through the company ranks would make 19th century novelist Horatio Alger proud. Born in Surrey, England, Cyril F. Greenhill came with his family to a farm on the Canadian prairie. As a teenager, Cyril went to Banff, Alberta, a resort town in the Canadian Rockies, and got a job as a pack train guide. For his efforts he received $75 a month plus room and board. A Banff hotel guest who was struck by the 19- year-old's ability and ambition invited Cyril to return to Toledo with him.

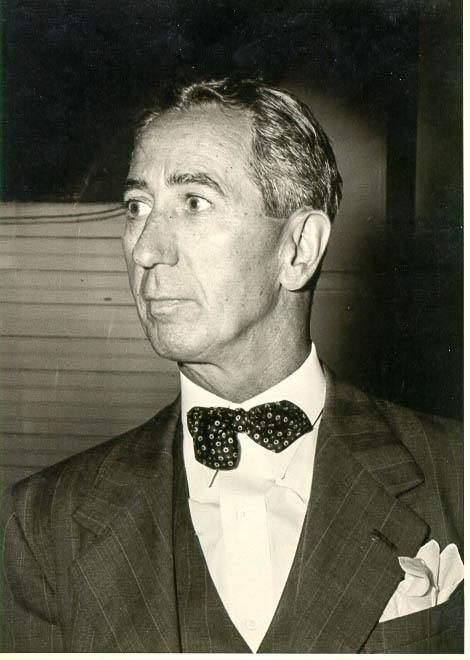

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin President from 1944-1954, photo mid-1950s.

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin President from 1944-1954, photo mid-1950s.

C.F. Greenhill arrived in Toledo in early 1913, and he immediately took a $5 a week job at the Ohio Electric Car Company. Within two months, however, the car company closed its doors and Cyril was jobless. Fortunately, he had met a member of the Acklin family and was offered a job sweeping the plant's floor. Greenhill accepted and began work the day after Thanksgiving, 1913 for 11 cents an hour. During the next twelve years Cyril climbed his way up the management ladder, working nearly every job in the plant along the way: press operator, then die setter, machine shop worker, time keeper, and shipping clerk. From there he crossed over into management – becoming an office boy – and then moved to production control and into purchasing. When the Acklin Stamping plant moved from its Dorr Street location to Nebraska Avenue in 1925, Greenhill became a general superintendent, then a salesman under Harold Jay, and eventually, by the early 1930s, Sales Manager. In 1936, Greenhill was named Vice President in charge of Sales, and in 1939 was named to the Acklin Board of Directors. When W.C. Acklin died late that same year, the company's business holdings went to Greenhill along with Frank Graper and Mr. Seeman. Greenhill maintained his Vice Presidency under Frank Graper, and when Mr. Graper died in 1944, Greenhill took over the presidency.

B. The Acklin "Family"

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin's fifth President

F. Cyril Greenhill, Acklin's fifth President

Grenhill's experiences throughout the various parts of the plant gave him a firsthand understanding of the rigors involved in each of these jobs, and a unique perspective on the concerns and demands of his employees. He understood the importance of unity and how each of the units functioned together as a whole. Greenhill articulated all of this in a handbook published for new employees in 1949. The handbook reflects C.F.'s vision of Acklin Stamping as an extended family where "when we do our part and our best to cooperate with the other members of the family, we find that our own job as well as the job of our fellow worker is made easier."

Under Greenhill's leadership Acklin again became a close knit family organization, as it had been during the days under Grafton Acklin and his sons. It was not uncommon for several generations of the same family or even husbands and wives to work side by side at Acklin. Ray Mierzwiak started at Acklin in 1929 working in a wide variety of positions but ended up in Inspection, where he worked alongside his wife Bernice for 22 years. Harold Krueger's father, Clarence Krueger, worked at Acklin before him, serving as a Welding Supervisor.

Acklin put quite a bit of bread on the table for the Houston family. All four brothers – Marshall, Edward, Luther, and Samuel – worked at Acklin during the 1950s. The Houston family, being African-American, was somewhat unique at Acklin. Toledo’s African-American population grew during the 1940s, as many moved to the North to find work in plentiful factory jobs. African-Americans made up a fairly small percentage of Acklin's workforce, but they made invaluable contributions. Unfortunately, very few African-Americans were promoted to management positions within the plant. Acklin did, however, make a conscious effort to combat racism at the plant, running ads in the newspaper encouraging friendship and unity among all races.

Greenhill made an effort at Acklin, more so than ever before in the company's history, to hire and promote from within the Acklin family. It was stressed time and again during this period, in both the Employment Manual and in the Acklin Press, that with the right attitude and the right amount of hard work, any employee in the Acklin family could rise through the ranks much, as Mr. Greenhill did. And nearly every manager or executive level employee at Acklin under Greenhill had been at Acklin for over a decade, often on a production level.

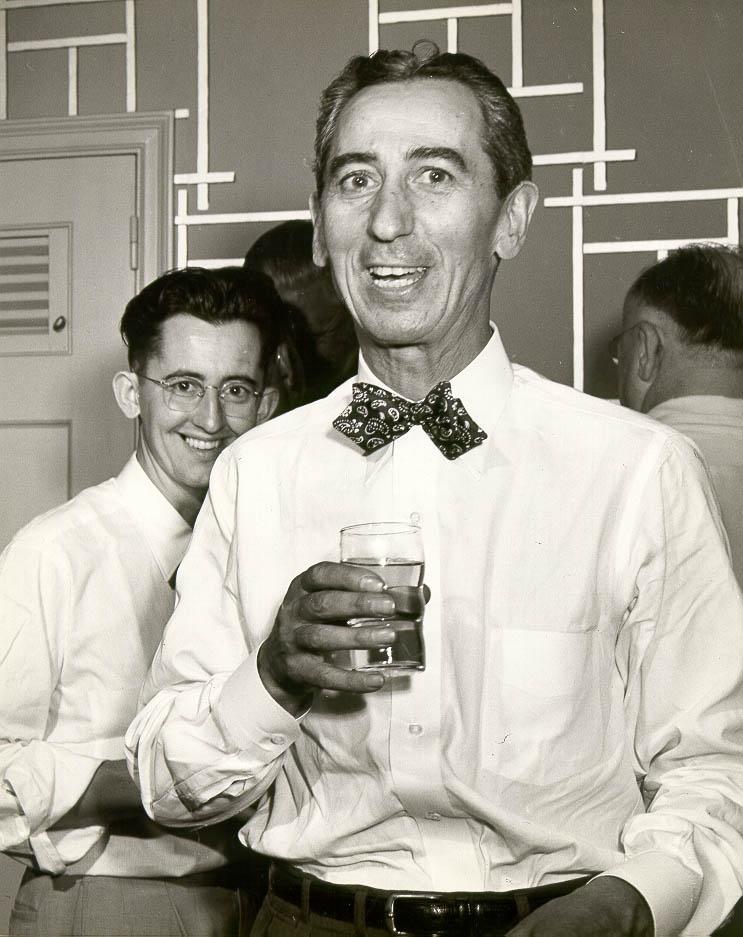

C.F. Greenhill, Acklin President at 1949 Salesman Conference

C.F. Greenhill, Acklin President at 1949 Salesman Conference

Throughout Acklin's history, employees had been getting together for various social activities, from bowling leagues and golf tournaments to picnics. But in 1947, a group of employees joined together to organize the Acklin Activities Club. The group drew up a constitution, charged $1.00 annual dues and a $1.00 membership fee in order to build a treasury, and elected officers. The company pledged $5.00 for each new member, up to $1,000. The group quickly gained well over 200 members and received the full amount from the company. The Acklin Activities Club organized a wide variety of events open to all members, ranging from dart ball and ping pong to Baseball and Bowling leagues.

The Acklin Baseball team competed in the C.I.O. League against such teams as Gordon Bumper, Plaskon, Mather Spring, and Willys Overland. The Bowling Leagues were a huge success, drawing between 100 and 150 players. The league was organized within the plant and divided into four categories – men’s and women’s for both the night and the day shifts. At the end of any sports season a celebratory dinner was often held.

The club also held parties, most notably a late summer company picnic open to all members and their families, and a Christmas party held for Acklin children. The annual picnic, held at various parks, often swelled to between 600 and 700 Acklinites and their families. The day's festivities included horseshoes and volleyball, lots of food, and general fun. All levels of Acklinites, from high level management to production line workers, played side by side. In fact, the softball game between the management and the union was a perennial draw.

Also starting in 1947 was a group known as the 25 year club, so named because of its only membership criteria – 25 years of employment at Acklin Stamping. The nine initial inductees included one woman, Pearl Rutkowski, who worked on the small line for most of those 25 years. Other inductees hiring dates went back into the late teens and the very earliest days of the company's history. The new inductees were honored in a banquet, a tradition that would continue annually for several decades. At the first induction the men were given fine cigars, the women orchids, and all were given lapel pins and a round of applause. The club, open to both retired and current employees, grew quickly, drawing up a constitution and electing officers. By the end of the 1950s there were 117 members, 103 of which remained active Acklin employees.

1947 also marked the arrival of The Acklin Press, a company newspaper that was published monthly. Edited by Robert Keller, personnel director, it kept Acklin Employees appraised of events and news around the plant. The Acklin Press covered all Acklin sporting events from the bowling league to fishing club, as well as documenting social events. It also described the business outlook of the company and the various parts being made. Designed for the entire family, the Acklin Press included in the center a "Family Fun Page" which contained cartoons and games for the children, as well as trivia, crosswords, and movie gossip for adults. The paper would continue monthly publication for the next several decades before finally succumbing to shrinking finances and gradually disappearing.

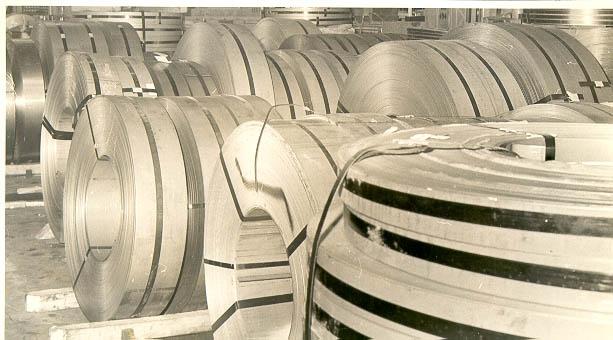

Steel Rolls as Raw Stamping Materials

Steel Rolls as Raw Stamping Materials

Under Greenhill, the company and the Union worked together to forge several projects beneficial to employees, including a company credit union; a more comprehensive pension and retirement plan; insurance plans; and paycheck deductions for savings bonds. Acklin pioneered many of these programs for the Toledo area and each of these programs provided Acklin employees with a variety of options and protections they didn't have before. These programs were negotiated through the union contract, and many of them expanded employee benefits and coverage throughout the years.

As a result of these programs and opportunities, Acklin became and remained a very close-knit organization, with employees spending time with one another both on and off the clock. Acklin was a family organization, one that encouraged loyalty, dedication, and hard work. Greenhill was a respected president and under his leadership the company's employees thrived.

C. Veterans Come Home

As World War II ended, many Acklin employees who had left to join the army began to return home to their jobs. Many women who a few years earlier had been working on the "Big Line" producing shell casings left to get married – often to returning Acklin veterans – and start families. The women who remained at Acklin shifted to clerical work or small line production.

The number of men returning to America looking for work was rather large. Many former Acklin employees returned to their old jobs, but as Acklin expanded to meet the demands of the civilian market (including the quickly growing refrigeration and air conditioning industries), quite a few new faces were hired as well.

Bernard Sztukowski worked in the die shop at Acklin before joining the Army's amphibious forces. He spent two years in the Pacific participating in three major and battles and was aboard the U.S.S. Missouri to witness the surrender of Japan on August 14th, 1945. He returned to Acklin in 1946 and married his fiancée, Lenore Muck, one of Acklin's two nurses in the First Aid room. He would remain at Acklin working in a variety of capacities.

Steve Przybylski, who he worked at Acklin since the depression, became a corporal with the Chemical Warfare Unit and played a part in four major battles in France, Germany, and the Rhineland during the war, including the Battle of the Bulge. Eugene Chapman also saw significant military action, serving for two full years in the Navy on an aircraft carrier in Manila Bay. He took part in seven major battles and his ship was hit twice by Japanese suicide planes.

Not every Acklin veteran saw as much action during the war as Bernard, Eugene, and Steve did. Some, like Les Carr, who entered in 1943, were bounced around the United States. He went to Miami Beach for basic training, then spent six months in Camp Campbell in Kentucky. From there he joined a Military Police outfit and spent the next year and a half between March Field, California and Abilene, Texas. Following his discharge in October of 1945, Les returned to Acklin.

Homer Percival, Acklin's general production foreman and an 18-year Acklinite, received a draft exemption based on his importance in and knowledge of Acklin's business. He instead served on the Selective Service Board, sending many of Acklin's employees off to the war – including Robert Keller, editor of the Acklin Press.

Not everyone returned from the war in the same shape as when they left. Harold Krueger enlisted in the Navy in 1942 and was sent to Machinist's Mate Service School in Dearborn, Michigan. Upon completion of the program he joined a ship and sailed through New Caledonia, New Guinea and the Admiralty Islands, serving as a machinist. In March of 1943, however, his leg was crushed between his ship and a tugboat. He spent over two years in Navy hospitals in the Pacific recovering from his injuries before finally returning to the United States in May of 1945. Harold recovered well from his injuries and would remain at Acklin for over 40 more years, eventually becoming plant manager during the mid-1980s.

-ORAL HISTORY NARRATIVES

D. Post War Production

Acklin Stamping Plant, 1946. 115,000 square feet.

Acklin Stamping Plant, 1946. 115,000 square feet.

As war time production ended, Acklin expanded its domestic production rapidly. The influx of experienced workers and a growing demand for consumer goods such as washing machines, refrigerators, and air conditioners caused rapid expansion at Acklin. In 1947 there were 475 employees, double the amount employed there three years prior during the peak days of the shell line and nearly as many as during the period of prosperity in the late 1920s.

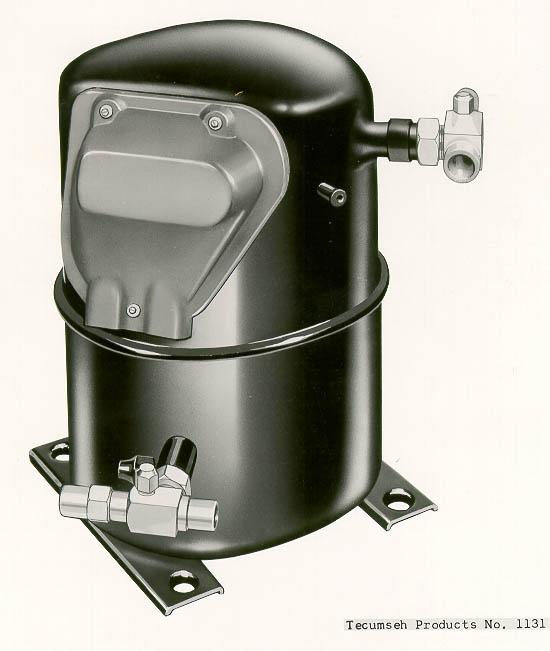

Shortly after the war, Acklin began to take orders from the Tecumseh Products Corporation of Tecumseh, Michigan. A leader in the compressor industry, Tecumseh had Acklin stamping compressor housings for use in the rapidly growing fields of refrigeration, air conditioning, and other cooling systems. Acklin also took large orders for parts from the Bendix Washing Machine Company of South Bend, Indiana.

During this period, Acklin was actively involved in seeking out new orders in an effort to supplement and maintain production levels. The rapidly expanding economy, particularly for domestic consumer goods, created a great deal of competition between various firms for the larger, steadier jobs.

When the Korean War broke out in the early 1950s, Acklin hoped to claim a large number of defense contracts, as they had during World War II. However, things didn't work out quite as they expected. During 1951, the Acklin Press reported that 95% of the orders placed by Acklin were for defense or war materials. Very few of these were produced, however, and most Acklin work remained civilian.

There was also a great deal of pressure placed upon the steel supply, with much of the higher quality steel going to the automotive industry, which was producing automobiles at a record rate. Some companies, when placing a stamping order with Acklin, would provide their own steel as well, but this was a fairly rare occurrence. Occasional labor disputes in the coal mining and steel industries would also hurt supply, forcing prices up. Or, if strikes seemed imminent but never materialized, Acklin was often left with an overstock of steel, which would force up production costs.

These pressures created the need for dedicated and concentrated effort on quality control for the jobs already received and a certain degree of fluctuation of employees. The air conditioning business itself was fairly cyclical, with production peaking in the late winter months in an effort to prepare for summer demand. Acklin had a policy for these inevitable summer layoffs that was based on seniority and rank; those who were laid off were placed on a list and they were the first individuals hired when production demands increased in the fall. Despite these fluctuations, Acklin remained one of the largest and most productive stamping plants in the Toledo area.

In 1947, Acklin's plant was 115,000 square feet in size, housing 150 presses and using 18,000 tons of steel per year. 35% of Acklin's business still relied on the automotive industry, supplying parts used in Willys-Overland, Studebaker, Chrysler, and GM cars. Another 35% of Acklin's business – approximately 4,000 units per day – went into the production of compressors and compressor parts used in refrigeration. Acklin also stamped parts for household appliances – washing machines, vacuum cleaners, and air conditioning – production that comprised 20% of Acklin's output. The remaining 10% was invested in the production of agricultural and other miscellaneous stampings.

Tecumseh wasn't the only company Acklin stamped compressor housings for. They also produced parts used in compressors assembled by General Electric and Westinghouse, but Tecumseh Products became an increasingly important source of business. In January of 1949, rather than lose Tecumseh as a customer, Acklin cut their prices on housings by 14 cents per unit, representing a significant loss of profit.

In 1950, Acklin began the production for Tecumseh Products of pistons used in the assembly of compressors. The pistons were designed through a joint effort of both Acklin and Tecumseh Engineers and this new job order provided 25 new jobs, mainly on the small press lines. This and other similar ventures show the co-operation and co-dependence the two companies were quickly forming.

In late 1951, Acklin was still searching widely for outside orders to increase their production and provide enough work to maintain the number of employees, but layoffs were inevitable. Several parts Acklin was producing had been underbid on in order to receive the order and the works involved, but were losing money on fairly rapidly. Steel was scarce and workers were uneasy about job security. Finding themselves in an increasingly complex and chaotic industrial marketplace, they began to attach increasing importance to Tecumseh's steady business.

E. Growing Consolidation - Toledo Industry in the 1950s

During the 1950s, many of Toledo’s industries underwent consolidations, mergers, and expansion. In 1953, Willys-Overland Motors Inc., still one of Toledo’s industrial leaders as its trademark defense product – the jeep – was becoming increasingly popular domestically, was sold to the Kaiser-Frazer Corporation for $62 million dollars, becoming the Willys Motor company. Doehler-Jarvis, a parts manufacturer, merged with the National Lead Company in 1953 as well. In 1957, two of Toledo’s oldest industries, the Haughton Elevator Company and the Toledo Scale Company, merged.

These mergers were fueled by a number of factors. First, increasingly sophisticated travel methods made it possible for goods to be manufactured in one area and cheaply shipped to another. This increased the importance of economies of scale – if you can produce large numbers of a product in a uniform manner, you can produce it and ship it more cheaply than your competitors. In order to remain competitive, large multinational corporations began to form, joining together older, more traditional businesses. These larger corporations began to compete on a national and international scale. Another reason for these conglomerations among the manufacturing sector was ever increasing technological change. New machines had to be purchased at an ever-increasing rate to stay competitive with other plants. In order to afford these purchases, larger corporations with larger profit margins were necessary.