By Benjamin Grillot, 2000

I. Early Days - "To such men as the late Grafton M. Acklin is the city of Toledo indebted for its prominence in the industrial world.." -The Story of the Maumee Valley, 1929.

A. Toledo, Ohio in 1911, A Backdrop

The story of Acklin Stamping, and really the story of Toledo's metal working industry, begins in 1911. The world was a radically different place in those days. Brand Whitlock, as Toledo's mayor, led a rapidly growing city of 170,000 people. The city and indeed the country were on the cusp of incredible technological change. In 1911, horses still dominated transportation and the speed limit was a mere 8 miles per hour. However this was all about to change in the next several years with the arrival of affordable automobiles, brought to the market by a number of companies including Toledo's own Willys-Overland Motor Company.

Acklin Stamping Plant, late 1930s

Acklin Stamping Plant, late 1930s

Throughout the city there was an overriding sense of optimism and hope for the future. Technological innovations were changing the fundamental ways people did things. However, the realities of industrial life were hard for working class men and women. The organization of major unions for unskilled workers had yet to take any effective steps towards improving worker safety or working conditions. A large number of immigrants were arriving in Toledo from around the world, primarily from Ireland and Eastern Europe.

The world was becoming a busy, noisy place. Industry was quickly making Toledo one of the most prominent and important cities in the Midwest. The Libbey Glass Company's arrival in Toledo from Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1888 had given Toledo a solid lead in the glass industry. Toledo was a prime location for industry because of its proximity to natural resources and key Midwestern markets like Chicago and Detroit. With the arrival of the Edward Ford Plate Glass Company (founded in 1898) and the Owens Bottle Machine Company (founded 1903), it soon became the center of the American glass industry. These companies revolutionized the glass industry by utilizing assembly line-style techniques of mass production.

Henry Ford, working outside of Detroit, pioneered techniques of mass production in the manufacturing of the automobile. This quickly emerging industry sixty miles north became increasingly important to Toledo at the turn of the century. Already a leader in the production of bicycles, Toledo firms utilized many of the same parts in the production of automobiles. The Lozier-Pope Company introduced its first steam-powered automobile -- "The Toledo" in 1900, but it was relatively lacking in both speed and power. The Pope Company's 1903 model, the "Pope-Toledo" was a more durable and popular automobile. Selling for about $3,000 (more than many people's annual salary), it was truly a luxury vehicle. In 1907, the Pope Company went bankrupt and remained in arrears for two years until it was purchased by John Willys in 1909. Willys paid off the debt and reorganized the company, forming the Willys-Overland Company, a firm that would later introduce the Jeep and the Wagoneer to the world.

An assembly line was used by Henry Ford in order to mass-produce perfectly identical automobiles in his Detroit plants. Each vehicle produced in this way was made up of thousands of pieces of steel, each precisely shaped, which were then assembled in factories. These pieces of metal were created at metal stamping plants, and as the automobile industry began to grow, so did the metal stamping industry.

Metal stamping is essentially a means of shaping sheets of metal into the precise shapes required by a wide variety of industries. Steel, an alloy of iron and carbon, is rolled into flat sheets at a mill and then shipped to a metal stamping plant. That sheet of metal is placed into the bed of a press and a large, carefully shaped object called a die is then pushed under extremely high pressure onto the steel, forming it in some way. In order to create a finished, usable result from a sheet of raw steel, several different operations are performed on increasingly precise presses.

There were two methods in which a company could fill its demands for these stamped metal parts-- either through the creation of an in-house department which would supply the company's entire needs, or through out-sourcing the parts to various "jobbing" concerns. In the Toledo area, three metal stamping companies arose in 1911 alone to meet the growing need.

It is not surprising that in early 1911, when Grafton Acklin, nearing his 60th birthday, looked to the future, he decided to retire as President of the Toledo Machine and Tool Company and open, with three of his sons, the Acklin Stamping Company. But in order to understand Grafton Acklin's vision it is important to understand the man himself, and his career which led up to the formation of this company.

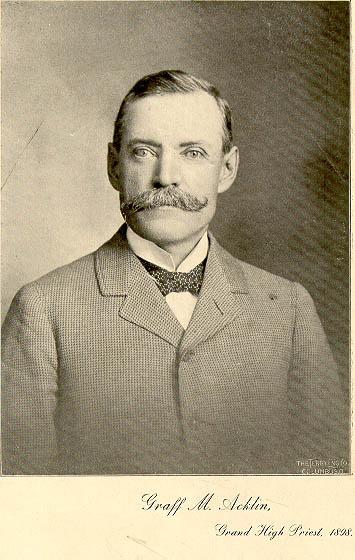

B. Grafton Acklin, Founder

Grafton Acklin, Acklin founder and president from 1911-1926. Photo from 1898.

Grafton Acklin, Acklin founder and president from 1911-1926. Photo from 1898.

Grafton Acklin was born on the banks of the Ohio River in Aberdeen, Ohio on the 30th of July, 1851. One of eight children, Grafton attended school in Aberdeen until the age of 15 when he moved, with his family, to Toledo. Mr. Acklin then began work in Toledo as a clerk in a wholesale grocery store, and after several years of hard work he became one of the owners. After some time, however, this partnership dissolved and Grafton and his partner, Samuel Wood, formed Acklin and Wood, a company supplying grocers with roast coffee and spices for wholesale.

By the late 1880s Grafton was considered one of the leaders of Toledo's business community. In 1896, the Toledo Tool and Machine Company asked Mr. Acklin to take over as the company's president. They hoped that his energy and vision would help the company achieve new levels of success.

The Toledo Machine and Tool Company had been founded in 1888 and specialized in the production of heavy metal working equipment -- presses, shears, and formers for the shaping of sheet iron. In 1897, the year following Grafton Acklin's appointment to Toledo Machine and Tool's helm, he expanded the company’s business overseas, supplying British bicycle firms with presses. In 1899 Toledo Machine and Tool introduced a special press for the making of gas stoves, and by 1900 had branched out into the making of planers, milling machines, boring mills, and cranes. Keeping up with technological innovations and the growing and changing nature of the industry, the company, under Grafton's leadership, continued to grow until it became one of the largest manufacturing and industrial concerns in Toledo.

By 1911, however, Grafton saw the emerging potential of the nascent automobile industry. He recognized that as mechanized production would grow there would be an ever increasing demand for stamped metal parts and that the potential for producing these parts would far outstrip the demand for the machines and presses to produce these parts. He was also nearing his 60th birthday and wanted to create a business with his three sons that would survive him.

C. The Family and the Founding

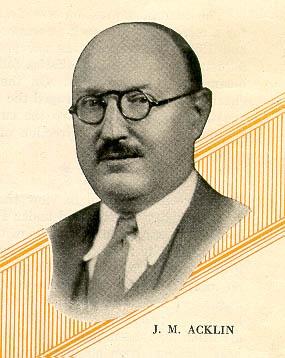

James Acklin, son of Grafton Acklin

James Acklin, son of Grafton Acklin

Acklin's business success had allowed his children to lead a fairly affluent lifestyle. The family lived in the fashionable West End district of Toledo, a community of extravagant Victorian homes. And as was common for the sons of Midwestern industrialists, all three Acklin sons received an east-coast, Ivy League education at Cornell University. James, the oldest at 27, graduated from college in 1906 and for several years worked with his father at the Toledo Machine and Tool Company.

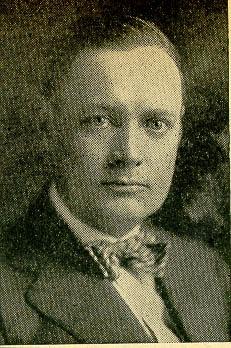

William, the youngest at 23, graduated from Cornell in 1910 and worked as a clerk at the Northern National Bank. Donald, the middle child at 25, had only a passing interest in the company and left shortly after its formation to pursue other career options.

Donald Acklin, Grafton's middle son

Donald Acklin, Grafton's middle son

So in the spring of 1911, Grafton Acklin, his sons, and Jerry Bingham – an outside investor – pulled together enough capital to found the Acklin Stamping Company. Grafton was the company's president, while James became Acklin Stamping's Vice President. The younger William was named the firm's secretary and treasurer. They opened up shop on the 1100 block of Dorr Street, using presses purchased mainly from Grafton's former company, the Toledo Machine and Tool Company. It was from these beginnings that Acklin sprang.

Drawing upon his extensive industrial business experience gained through his tenure at the Toledo Machine and Tool Company, Grafton Acklin's leadership quickly proved effective. Grafton's contacts in the metal working industry, as well as his strong sales and marketing ability, allowed Acklin Stamping to grow considerably in a fairly short period of time.

Picking up on the rising demand for automotive products, Acklin Stamping landed a job producing steel steering wheel spiders for automobiles. Acklin Stamping Company received production rights for an exclusive patent held by the Beck Frost Corporation and then supplied those steering wheel parts to the Willys-Overland Company.

As a job stamping plant, Acklin Stamping could hardly expect Willys-Overland alone to support them. In order to stay competitive, Acklin Stamping produced a wide variety of stampings for a large number of companies. At one point, the Ohio Gas Company asked Acklin Stamping to create a display case in which they could show off canisters of their oil at gas stations. Acklin Stamping agreed and stamped several thousand of them. After a brief trial, it was clear they weren't working out and the order dried up as quickly as it came.

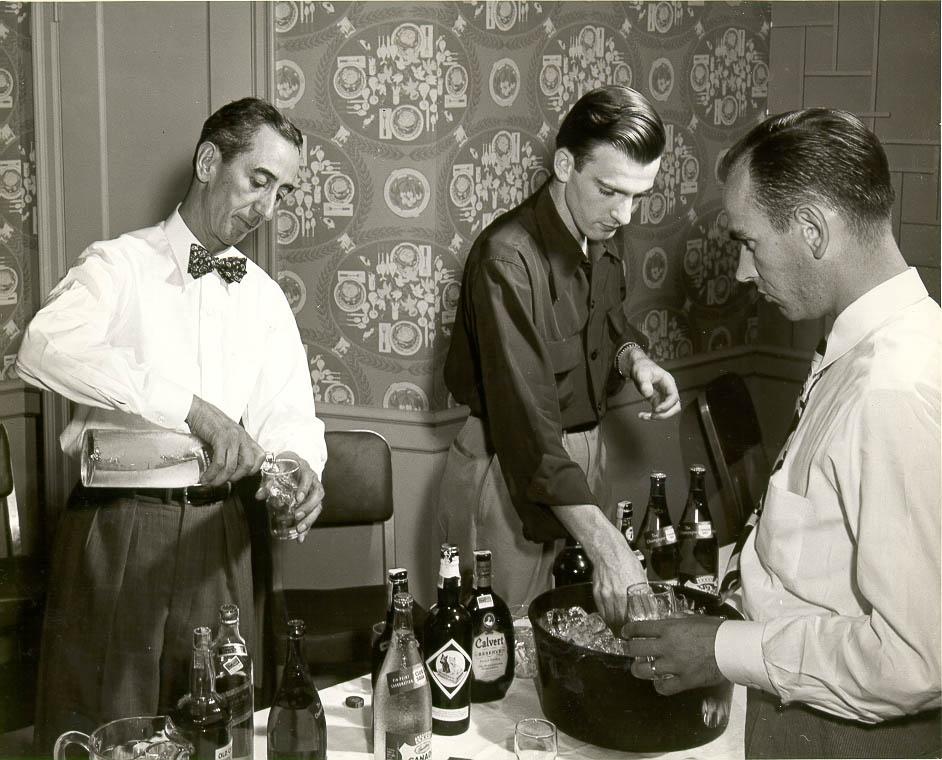

C.F. Greenhill pouring a drink. 1949 Salesmans Conference

C.F. Greenhill pouring a drink. 1949 Salesmans Conference

This shifting of production was fairly common. Without any one major customer, Acklin Stamping stamped an assortment of products during its early years including an order for muffler caps used in motorcycle engines. At the same time, they stamped everything from pulleys used in window sashes to metal vending machines used for dispensing Wrigley's gum and other candies. They stamped fuse socket holders, push lawn mowers, and metal splicers used in the repair of trolley car poles.

In the spring of 1917, when America declared war on Germany, beginning America's involvement in the First World War, Acklin was ready. The plant quickly shifted into the production of food containers, ammunition, and parts for Quartermaster trucks. By the time the war ended, Acklin had 125 presses, the largest of which was a 500 ton press, able to apply 500 tons of pressure to a single sheet of steel. The plant, then located in the 1600 block of Dorr Street at the corner of Woodland Avenue, shifted its production back to civilian goods.

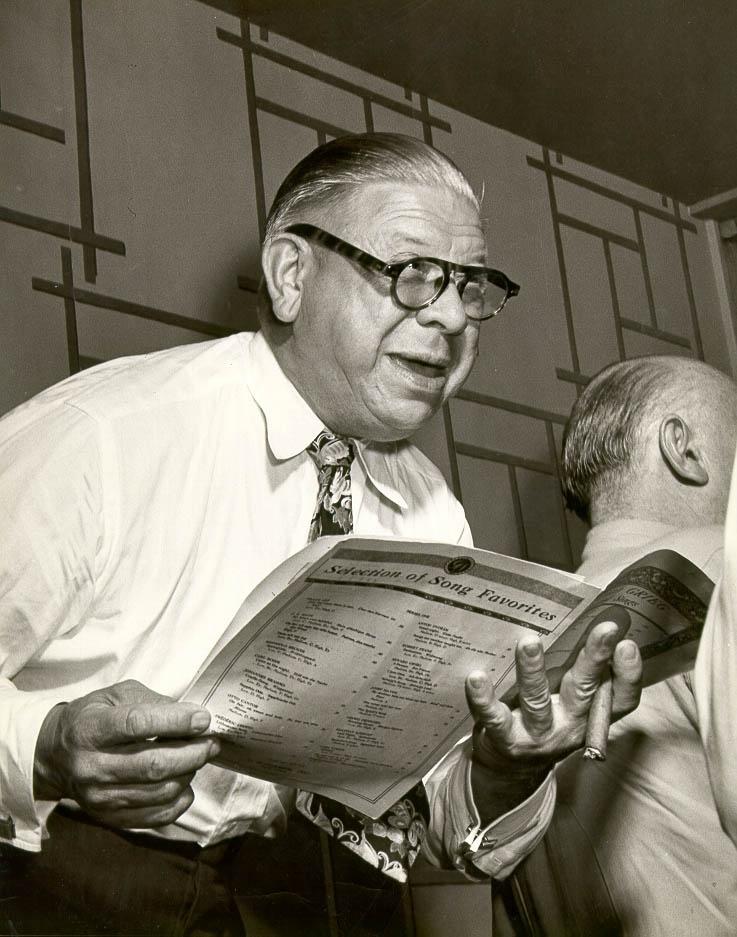

W.H. Dahlberg leading singing after sales conference. 1949.

W.H. Dahlberg leading singing after sales conference. 1949.

By 1925 the company's nearly 300 employees had outgrown the facilities of the 40,000 square foot Dorr Street plant and plans were made to build a new factory, this time on Nebraska Avenue. The new plant, built by the Toledo architectural firm of Langdon and Hohly, was nearly 90,000 square feet in size when constructed and was connected to the New York Central railroad. The new plant allowed Acklin to employ nearly 500 employees over the next year, cementing their role as one of the largest job-stamping plants in Ohio and the nation.

Following Grafton Acklin's death in early 1926, the company remained in the Acklin family’s hands. James Acklin, formerly Vice President of the company, stepped up to the presidency. James maintained the company's steady and substantial growth through the last half of the 1920s, and with a steady hand on the company's rudder, managed to weather the storm of the Great Depression.

But unfortunately, just as Acklin's business and the country's economy were beginning to recover under Roosevelt's New Deal, tragedy struck the family. In 1936, at the age of 52, James Acklin died in an automobile accident, leaving the helm of the company to his brother William. William ran the company without incident until 1939, when he passed away as well. Following the death of William Acklin, the company's holdings were transferred out of the Acklin family for the first time, marking the end of an era. Three Acklin executives, F.C. Greenhill; A.E. Seeman; and Frank Graper, divided the company between them. Frank Graper picked up where William left off, retaining the company's family name, and continuing its policies of promotion from within and respect and care for its employees, while Greenhill and Seeman remained in their respective executive positions.