by Timothy Messer-Kruse

A monument is a curious way to record history. It is the oldest, most ancient form of history writing (what else is a pyramid or a statue but a memorial of some past?) and still remains a popular means of expressing historical ideas. Like the ancients, our society still etches its feats and stories in stone and metal.

A historical monument is a particular means of marking history. Unlike our other methods of remembering - through writing or speaking - a monument permits no dialogue. It stands, immovable, unalterable, silent and alone, speaking and never hearing. A speaker in a lecture hall can be interrupted, questioned, debated with. A book can be challenged by reviewers and argued with by other books that will stand shoulder to shoulder with them down through time on the shelves of our libraries. But a monument dominates its place. It has endurance - it shouts out during all the hours of the day and all the days of the year, year after year, to all who pass by "this is the way things have been - these are the things that are most important - and you should remember and honor them."

ACLU's Bill of Rights Monument

ACLU's Bill of Rights Monument

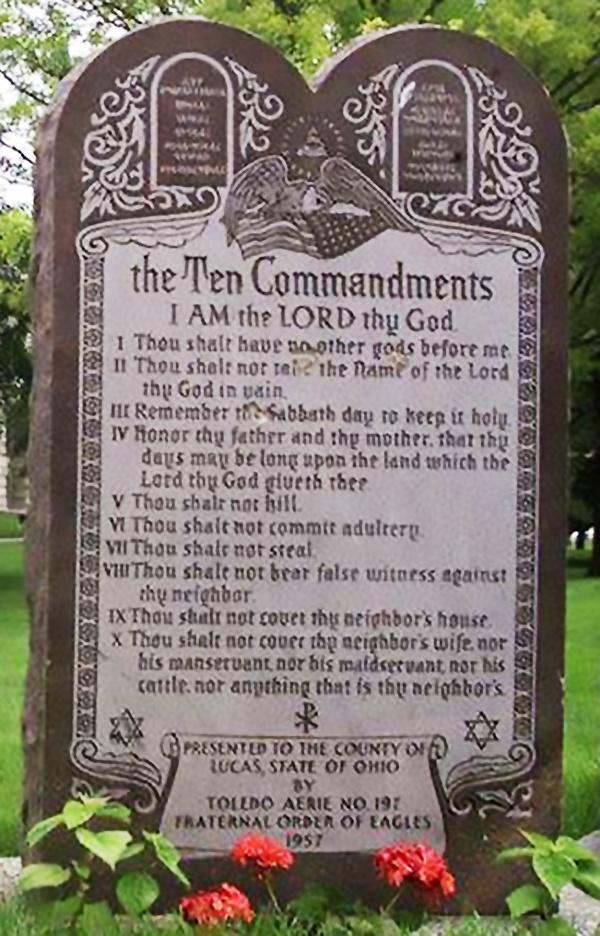

A monument's claim can only be challenged by illegal acts of defacement or by the placement of another monument nearby. Monuments are made of stone and bronze, not only because these materials will last through time, but also because they take great effort to alter and because they are expensive. To debate a monument with another monument is costly, though it is sometimes done (the A.C.L.U.'s Bill of Rights monument was placed a dozen yards from the ****'s Ten Commandments on the Lucas County Courthouse Square). Its more common for individuals to attempt to add a comment to one already standing, though these vandal scrawlings carry none of the credibility of a monument's precisely chiseled letters. Perhaps it is because historical monuments are the most one-sided means of remembering the past that they have been continuously used for over ten thousand years.

One of the purposes of this exhibit is to allow everyone the opportunity to argue with their monuments. Each monument or marker has been given its own page upon which is displayed its text and image. Alongside these words are blank spaces upon which anyone may inscribe their own responses, arguments, or memorials. Through this means the monopoly of history that monuments represent is at least partially overturned.

The power of a monument, unlike other types of history remembering, is drawn from its surroundings, its place. Some monuments are placed in an important, and highly trafficked public place as a way of emphasizing the importance of a person or event. The manicured flowerbeds and classical architecture of the Lucas County Courthouse not only serves as a backdrop to the William McKinley Monument, they dramatically add to its air of dignity and importance. In contrast, the historical marker that notes the location of the city's first hospital sits on a traffic island in the middle of a hospital's busy driveway. The only way to actually read the sign is to park illegally, partially blocking traffic, and walking across a swath of grass. (Within five minutes of my making this trek to read the sign, hospital security was deployed to tell me that this was private property and that I needed written permission to be where I was.) Such an inaccessible location says to the world, 'something once happened here, but its not of much importance.'

Where things are placed can have political dimensions as well. For example, it is interesting that the Spanish-American War Veterans Monument, also located on the courthouse square, is situated on the opposite side of the building so that it is impossible to view both monuments simultaneously. Though the deaths of the soldiers remembered on one side of the building was the result of orders given by the man immortalized on the other, this relationship is guiltily hidden by the visual separation of the two.

It is for this reason that merely photographing the monuments themselves cannot reveal their entire meaning. Rather, the monuments and their surroundings must be shown together, a task that traditional photography has only a limited ability to do but that computers now make possible in new ways. VR panorama photography allows for the capturing of a complete three hundred and sixty degree view of a landscape. Viewed on a computer these panoramas are seamless and controllable by the viewer and reveals more than what the monument tells you to look at.[1]

Finally, this exhibit is also an inventory of what generations of people in Toledo and Lucas County have considered worth remembering. The list of what has been marked and monumented reveals more about what each generation has valued than what of historical importance has actually occurred in the area. When people of a certain age construct a monument to the past, they are in fact not immortalizing the past, but preserving a piece of themselves. Of the monuments found below, about a third commemorate business or commerce; as many recognize the slain in our nation's wars; some chronicle the history of government or its public servants; the remainder primarily mark the founding of charitable and cultural institutions. Only one memorial, the Richard Gosser Memorial, notes an achievement of workers, only two celebrate neighborhoods, and only one recognizes the diversity of Toledo's population. Judging by our memorials, we are a community concerned mostly with business and respectful of the sacrifices of our defenders.

Timothy Messer-Kruse, University of Toledo, September 11, 2000